- This case concerns claims in negligence arising from a series of motor vehicle collisions that all occurred within a few minutes of each other before dawn on 15 October 2015, on an unlit section of the eastbound carriageway of the M20 motorway between junctions 8 and 9 near Charing in Kent.

- The persons involved in the collisions were as follows:

i) Mr. Daniel Martini, the driver of a black Audi TT. His insurance company is Southern Rock Insurance Company (“SRI”).

ii) Ms Eriselda Zeqo, the passenger in the black Audi TT driven by Mr. Martini.

iii) Mr. Jason Mason, the driver of a white Vauxhall Vivaro van. His insurance company is AXA Corporate Solutions Assurance SA (“AXA”).

iv) Mr. Stanslaw Wylecial, the driver of a white Fiat Ducato van. His insurance company is Royal & Sun Alliance (“RSA”).

v) Mr. Alexei Sova, the driver of a red Scania heavy goods vehicle (“HGV”). He is a non-party.

vi) Mr. Horativ Aruncutean, the driver of a blue Mercedes HGV. He is a non-party.

- In brief, the key events are these. Mr. Stanislaw Wylecial fell asleep at the wheel of his Fiat van and crashed into the back of a Mercedes HGV. His Fiat van then remained stranded and unlit in the middle lane of the dark carriageway. Shortly afterwards, a Scania HGV travelling in lane 1 approached the scene. It travelled all the way across into lane 3 to avoid a collision, slowing down as it went. Mr. Daniel Martini and Ms Eriselda Zeqo were in a black Audi TT, proceeding in lane 3 behind the Scania, and driving at around 65-70 mph. When the Scania entered his lane, Mr. Martini braked and swerved left, to try to avoid hitting it. However, as a result of swerving left, he collided with the Fiat in lane 2, which he had not seen, and his car then ricocheted across to hit the rear of the Scania in lane 3. Mr. Martini’s Audi came to a stop in the carriageway a short distance ahead of the Fiat van. He and his passenger got out and made it on foot to the grass verge beyond the hard shoulder. Finally, a Vauxhall Vivaro driven by Mr Jason Mason approached the scene. It crashed into the Fiat van in lane 2, and then spun across the highway, striking Mr. Martini and Ms Zeqo where they were standing on the grass verge.

- The serious damage and injuries to which these collisions gave rise became the subject of two separate claims in this Court:

i) The first was a claim which was issued on 10 October 2018. It was originally given the case reference HQ18PO3607, but following the establishment of the CE filing system the case was assigned reference number 2018-004840 (“the 4840 claim”). It was brought by Mr. Martini and Ms Zeqo, as the First and Second Claimants, against (i) Royal and Sun Alliance Insurance plc (“RSA”), the insurers of Mr. Wylecial, and (ii) AXA Insurance UK plc (“AXA”), the insurers of Mr. Mason. A defence was entered by RSA (i.e. the First Defendant), contending among other matters that Mr. Martini’s negligent driving had been a cause of the damage and injuries. Mr. Martini’s insurers, Southern Rock Insurance Company Ltd, (“SRI”) were added as the Third Defendant.

ii) The second was a claim under reference number 2019-004298 (“the 4298 claim”), issued on 19 October 2018. It was brought by Mr. Mason against (a) T&W Bakeries Enterprises Ltd., the employers of the Fiat van driver, Mr. Wylecial, and (b) RSA, Mr. Wylecial’s insurers.

- By Order of Master Thornett on 2 June 2020, the two sets of proceedings were directed to be tried together on issues of liability only. A few days ahead of the trial before me, the 4298 claim was compromised, leaving only the 4840 claim. The trial of this claim was heard over 4 days beginning on 29 November 2021. This is the judgment on the liability issues.

The facts in more detail

- The relevant section of the M20 motorway has no street lighting. Both carriageways consist of 3 lanes and a hard shoulder with a wearing course of concrete. The northern edge of the eastbound carriageway consists of a 45-degree kerb followed by a narrow grass verge leading down a steep embankment into dense woodland. The carriageway separation is by way of a central French drain and metal safety barrier. At around 4.40am on 15 October 2015, it was still dark (before dawn), and there was light and possibly intermittent rain. The road surface was wet.

- A blue Mercedes HGV being driven by Mr. Aruncutean in the eastbound carriageway was established in the inside lane (lane 1). The tachograph evidence shows it was travelling at 56mph until it was struck from behind.

- The vehicle that collided with the blue Mercedes HGV was the white Fiat Ducato van driven by Mr. Wylecial. The Fiat was travelling at between 71 and 86 mph. It is common ground that Mr. Wylecial drove negligently. He did not appreciate that he was closing in on the Mercedes, which he ought to have been capable of doing between 66-93 metres back. He fell asleep at the wheel.

- After the collision, which caused substantial damage to the Fiat across its entire front, the Fiat came to rest in the middle lane (lane 2). It was probably angled slightly towards the offside. Passers-by reported to the police that the Fiat was unlit. When the trial commenced, Mr. Ferris on behalf of the First Defendant (the insurer of the Fiat driver, Mr. Wylecial) contended that the hazard lights on the Fiat were probably operative after the collision. This contention was based on an account given by Mr. Wylecial, who had said that his rear hazard lights had come on automatically. However, after the close of the evidence, Mr. Ferris realistically conceded that the Fiat probably was unlit after the collision with the Mercedes HGV.

- A photograph showing the extensive damage to the Fiat van is at Picture 1 below. At the trial, Ms Symington, representing the Second Defendant, drew attention to the visible dangling wires from the Fiat’s fusebox, to support the suggestion that it was highly unlikely that the Fiat’s hazard lights were operative following the collision, and that the Fiat therefore represented an entirely unlit hazard in the central lane of the carriageway before sunrise that day. In the light of the concession made in closing submissions by Mr. Ferris to which I have already referred that the Fiat was probably entirely unlit, there was ultimately no dispute about this.

Picture 1

- The Mercedes HGV came to a stop on the hard shoulder, some distance ahead. It was, in part, jutting out into lane 1. Its rear offside lights had been destroyed by the collision, as shown in Picture 2 below. It was displaying a nearside tail-light, and probably its hazard light was switched on (so giving the appearance of indicating left). At some stage, a warning triangle and light beacon were placed somewhere in the carriageway to the west of the collision (behind the accident scene) by the Mercedes driver, but these do not appear to have played a part in the subsequent events, and by the end of the trial no reliance was placed upon their presence by any party.

Picture 2

- Probably a matter of minutes later (at most), the red Scania HGV driven by Mr. Alexei Sova approached the scene. It was travelling at around 53mph, and according to Mr. Sova’s account given to a police officer shortly after 10.45am that day, it was initially established in lane 1. According to the police officer’s notes, Mr. Sova said:

“There was not much traffic, I saw in the distance some debris in the road. I thought a lorry had lost something. I didn’t think it was an accident. I was the driver. I didn’t see any lights. When I got closer I saw an accident and slowed down and indicated to drive past it. As I was passing I felt something but didn’t know what. After the accident I pulled to the right and stopped. I and my colleague got out and saw our vehicle had damage on the left side. We went to see what was going on and saw a vehicle in a ditch…”.

- The tachograph evidence from the Scania showed that the vehicle gradually slowed over a distance of about 92m, from 53mph to about 31-32 mph. The Scania then maintained that speed for about 6 seconds, over a further distance of about 84m. After that, it began a second phase of deceleration and eventually came to a stop.

- The factual and expert witness evidence at trial established that the Scania first moved from lane 1 into lane 2, and then from lane 2 into lane 3, as it was slowing down on the approach to the accident scene. By moving into lane 3, the Scania driver managed to avoid colliding with the severely damaged Fiat, which was motionless and unlit in the central lane directly ahead of him as he drove forwards.

- The weight of the evidence, including the account given by the Scania driver himself on the day of the collisions, was that he did not engage in any emergency braking as he moved across the carriageway into lane 3. Rather, he probably applied a degree of light to moderate braking before releasing his vehicle’s brakes as he passed through the scene. It is possible that at least some of the deceleration was achieved by engine braking alone, with the result that there also might not have been brake lights visible to any vehicles behind the Scania on the carriageway during all or part of its manoeuvre.

- The experts in their joint statement considered a scenario in which the final part of the manoeuvre of the Scania across the carriageway, from lane 2 into lane 3, was “more towards being that of an emergency swerve” in order to avoid the stationary Fiat. The parties were divided on this question, and the experts found it impossible to arrive at a clear conclusion based on the physical evidence. Mr. Parry’s oral evidence was: “We don’t know how Mr. Sova moved from lane 2 to lane 3. There is no physical evidence. So it could have been a more urgent move because of the stationary vehicle ahead in lane 2.”

- I consider that the totality of the available evidence does point to it being more likely than not that the final part of the Scania’s manoeuvre was indeed rapid, although it is of course impossible to be precise. In this regard, I take into account in particular:

i) Mr. Sova’s reported account of his actions suggests that he was acting to avoid colliding with the damaged unlit Fiat in his path (“When I got closer I saw an accident and slowed down and indicated to drive past it”);

ii) it is probable that Mr. Sova was using his dipped head beams, since there is no suggestion that he turned on his full beams;

iii) the joint opinion of the experts is that the range in which dipped head beams on the Scania would have illuminated the stricken Fiat in the road ahead, to allow Mr. Sova to see it, would have been about 60m;

iv) the steady speed of 31-32 mph that the Scania maintained over roughly a 6-second period probably began shortly before, or when, the vehicle entered the fast lane, after the period of deceleration;

v) as Mr. Blakesley QC pointed out, that would have left Mr. Sova not much more than 2 seconds to react to the presence of the unlit Fiat ahead.

- Meanwhile, coming up behind the slow-moving Scania HGV as it entered lane 3 was the black Audi TT driven by Mr. Martini, with his passenger Ms Zeqo. By his account, Mr. Martini was travelling at around 65-70 mph. The four experts agree that this reported speed is broadly consistent with the physical evidence, and Mr. Martini’s account is unchallenged in this respect.

- Mr. Martini did not see (or, as Mr. Blakesley QC more accurately put it, “register”) the Scania HGV until it was in front of him in the fast lane. It appeared to him to have come from the sky. He does not recall that it was indicating, nor that its tail-lights were illuminated.

- Mr. Martini’s vehicle braked sharply and swerved from lane 3 into lane 2, in order to avoid colliding with the Scania that had moved in front of him in the fast lane (in which large HGVs are generally prohibited from driving), and which was travelling at only around 31 mph. As a result of Mr. Martini’s swerve left, the Audi collided with the stationary unlit Fiat in lane 2, striking its offside.

- That collision with the Fiat deflected the Audi immediately back towards the rear nearside corner of the Scania trailer, in the fast lane. The Audi is estimated to have been travelling at about 40 mph on impact with the Scania. After the collision with the Scania, the Audi travelled forward another 14-20m before coming to a stop. It is likely that the Audi was undertaking hard or emergency braking at least from the time of the collision with the Fiat until its final point of rest.

- The Audi stopped about 25m ahead of the Fiat, straddling lanes 1 and 2. Its position on the carriageway, and its damaged state, can be seen from Picture 3.

Picture 3

- Mr. Martini said that, after a few seconds, he turned on the hazard warning lights, and stopped the engine. He took a moment to gather his senses. He did not see the Mercedes HGV ahead on the hard shoulder. He put his hazard lights on, and he remembered hearing them click. He put his handbrake on and turned off the ignition. He undid his seatbelt and got out of the car. He waited for his passenger, Ms Zeqo, to get out too, but she did not do so immediately. He tried to open her door, and saw it was damaged. He had to force the door open. He remembered needing to persuade Ms Zeqo to leave the vehicle, and that he encouraged her by saying it was the law in England - “you have to get out to safety”.

- They then both went across lane 1 of the motorway to the hard shoulder. Before they could do so, one lorry travelling in lane 1 let them pass through. It was going slowly, to let them cross. It may even have stopped to do so.

- As respects the Scania HGV, it is not known where the vehicle initially came to rest after the Audi struck it. The tachograph evidence shows only that the Scania was stationary for about 6 minutes, and then was moved over a period of almost 2 minutes. Mr. Sova’s initial account was that he “pulled to the right and stopped” (see paragraph 12 above), i.e. in the fast lane. The parties were divided on whether Mr. Sova did indeed pull to the right and stop on the carriageway, or whether there is a mistake and Mr. Sova meant to say that he pulled over to the left and stopped on the hard shoulder. It is plausible, and in my judgment most probable in the circumstances, that Mr. Sova did mean to say that he pulled to the left and stopped on the hard shoulder. At least one of the experts (Mr. Davey) supported this in his main report.

- The Scania was finally parked tightly in the hard shoulder with the rear of its trailer about 25m east of the front of the Audi, and about 21m ahead of the Mercedes that had stopped and was straddling the hard shoulder and lane 1.

- A consequence of the collision between the Audi and the Scania was that the Scania sustained impact damage at the rear nearside of its trailer. It is unlikely that the lights at the rear nearside of the Scania’s trailer functioned after that point. The rear offside trailer and the tractor unit lights were unlikely to have been affected, and probably remained operational. There is no evidence that Mr. Sova switched on the Scania’s hazard warning lights. When the Scania was situated on the hard shoulder, any light that it displayed would have been masked by the Mercedes HGV from the view of other cars approaching the scene on the eastbound carriageway.

- At some point in the following minutes, a Vauxhall Vivaro van driven by Mr. Jason Mason approached the area of the accidents, driving in lane 1. A colleague, Mr. Jones, was sitting in the front passenger seat. Mr. Mason had overtaken a white Ford van driven by a Mr. Hendrick shortly before reaching the area of the accidents, and he had moved about 200-300m ahead of Mr. Hendrick’s van. Mr. Hendrick estimated that the Vauxhall was moving at a speed of 70-75mph. There was nothing to suggest to the experts from the physical evidence that the approach and impact speed of the Vauxhall was any different from that estimate.

- The experts agreed in their joint statement for the trial that, with the exception of possibly two lights flashing on the vehicles ahead, the motorway would have been in darkness. Those two lights would have been the rear nearside light of the Mercedes in the hard shoulder, and the rear nearside hazard light on the Audi, straddling lanes 1 and 2. This would have been an unusual configuration, but not such as to amount to notification to a driver that an immediate danger lay ahead.

- As Mr. Mason approached the stranded unlit Fiat, he steered right into lane 2 and, according to Mr. Hendrick, Mr. Mason applied his brakes. It is unclear whether the trigger for Mr. Mason to move from lane 1 was the result of him reacting to a light on the stationary Mercedes over 100m ahead, or to something else.

- Mr. Mason’s dipped headlights would have illuminated the stranded Fiat in lane 2 at a distance of at most 60m. Since he was still travelling at around 70mph, the Fiat would have started to become illuminated less than 2 seconds before the Vauxhall collided with it. The Vauxhall struck the Fiat at speed, then travelled out of control to the side of the carriageway and beyond, where it also struck Mr. Martini and Ms Zeqo where they were standing on the grass verge, causing them both serious injuries.

- Mr. Hendrick, driving behind the Vauxhall, gave a report that before the accident with the Vauxhall happened, he saw two hazard lights flashing ahead, and he thought they were on the hard shoulder or in lane 1. His own response was to move from lane 1 into lane 2 as a precaution. He then saw Mr. Mason’s Vauxhall collide with the unlit Fiat. He recorded his belief that if the Vauxhall had not collided with it, he would have done so instead. At the criminal trial of Mr. Wylecial (driver of the Fiat), Mr. Hendrick said: “I didn’t know anything was there until he’d [i.e. Mr. Mason] hit it.”

- At the trial before me:

i) the Fiat/Mercedes collision was called collision 1;

ii) the Audi/Fiat collision was called collision 2;

iii) the Audi/Scania collision was called collision 3;

iv) the Vauxhall/Fiat collision was called collision 4.

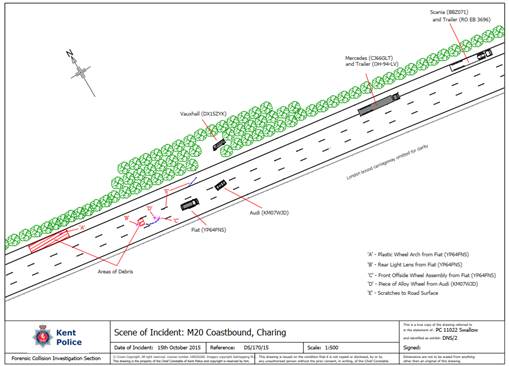

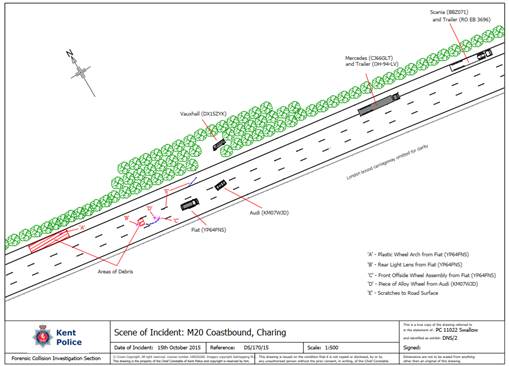

- The final positions of these affected vehicles following collisions 1-4 can be seen from Picture 4 below.

Picture 4

- Following the accident, Mr. Wylecial was prosecuted in the Crown Court at Maidstone in June 2017, on one count of dangerous driving, and on four counts of causing serious injury by dangerous driving. The four counts of causing serious injury related to, respectively, Mr. Martini, Ms Zeqo, Mr. Mason and his passenger Mr. Jones.

- The Judge (His Honour Judge Jeremy Carey) instructed the jury in his summing-up:

“In respect of counts 2 to 5, you have to be sure that the defendant’s dangerous driving was a cause of the serious injuries sustained by the four victims. Cause means any cause more than a trifling or insignificant cause.” The judge also noted: “…the defence submit that the driving of Jason Mason was such that it had the effect of breaking the link between the defendant’s driving and the injuries which the victims sustained when Mr. Mason’s car careered out of control after colliding at speed with the Ducato. So you must pause and answer this question: was the driving of Mr. Mason such a new and intervening act that it could not be said that the dangerous driving of the defendant was a cause of the serious injuries?”

- Mr. Wylecial was convicted on all five counts on 14 June 2017. He was sentenced to 14 months’ imprisonment for the four offences of causing serious injury by dangerous driving, and 6 months’ imprisonment concurrently for the dangerous driving offence.

- The Judge stated in particular, in his sentencing remarks:

“Having presided over your trial and in the light of the jury’s verdicts, I reach the following sure conclusions upon which you will be sentenced …

“One, you fell asleep at the wheel of your delivery vehicle as you drove along the M20. The duration of that sleep was short, but had devastating consequences …

…

“Four, the fact of your collision, which on the jury’s verdict was caused by your dangerous driving, created a very dangerous hazard in the way of approaching vehicles from the direction in which you had been travelling. Some avoided colliding with your van in the middle lane, particularly when the obstacles in their way became more numerous and the lighting more obvious. Others did not, including the Audi driven by Mr. Martini and the Vauxhall van driven by Mr. Mason.

“Five, the collision between the Vauxhall and your vehicle and the subsequent path of the Vauxhall, out of control, across the hard shoulder, where it hit Mr. Martini and Ms Zecu [sic], causing them very serious injury indeed, was on any view a cause of the serious injury sustained by them and by the occupants of the Vauxhall.”

The parties’ cases

- The primary target of the claims in negligence brought by Mr. Martini and Ms Zeqo is RSA, the insurers of Mr. Wylecial and the First Defendant.

- The central thrust of RSA’s case, at least as it stood until the start of the trial, was that:

i) although their insured, Mr. Wylecial, was admittedly negligent and caused the first collision between his vehicle (the Fiat) and the Mercedes HGV, his negligence was not an operative legal cause of any of the subsequent collisions, nor of the resulting damage and injuries sustained by the Claimants. At the very least Mr. Wylecial’s negligence was not the sole legal cause of the subsequent collisions and the resulting damage and injuries;

ii) Mr. Martini bears responsibility for the collisions between his Audi and, respectively, the Scania and the Fiat. He did not keep a proper lookout, and he failed to exercise reasonable care by slowing down in lane 3 to avoid the Scania lorry that was moving in front of him, despite having sufficient time and space in which to do so;

iii) no injuries were suffered by any of the Claimants until the subsequent collision by Mr. Mason’s Vauxhall van with the Fiat;

iv) Mr. Mason negligently failed to slow down before the collision with the stricken Fiat even though he had warnings of there being hazards ahead by reason of various vehicle hazard warning lights flashing (on the Audi, Mercedes, Scania, and Fiat). If Mr. Mason had exercised reasonable care, he would have avoided the collision with the Fiat, and there would have been no consequent injuries suffered by Mr. Martini and Ms Zeqo from their position standing on the grass verge.

- The other parties, apart from Mr. Mason, reacted to RSA’s pleaded case by advancing various claims and cross-claims inter se, as well as against RSA:

i) Mr. Martini brought his damages claim also against the Second Defendant AXA, Mr. Mason’s insurers;

ii) Ms Zeqo similarly brought her claim also against the Second Defendant AXA; she also mounted her claim against Mr. Martini and his insurers SRI, i.e. the Third Defendant;

iii) The Second Defendant AXA made a contribution claim against Mr. Martini’s insurers, SRI.

- Accordingly, at the opening of the trial before me, the First Defendant RSA’s primary position was that the negligent driving of Mr. Martini and/or Mr. Mason were each novus actus interveniens, and that the chain of causation between Mr. Wylecial’s original act of negligence and the injuries suffered by the Claimants, had been broken.

- Ms Symington on behalf of the Second Defendant AXA, and Mr. Blakesley QC on behalf of the Third Defendant SRI, each drew my attention to s.11 of the Civil Evidence Act 1968, and in particular to sub-paragraph (2), which states:

“In any civil proceedings in which by virtue of this section a person is proved to have been convicted of an offence by or before any court in the United Kingdom … (a) he shall be taken to have committed that offence unless the contrary is proved” (emphasis added).

- They argued that the First Defendant’s case that Mr. Wylecial’s negligence was not an operative cause of the injuries sustained by any of the Claimants - despite Mr. Wylecial having been convicted for causing those injuries by dangerous driving - was not tenable, or hardly so, since the First Defendant was bringing forward no material new evidence in support of that case beyond what had been available to the jury at the criminal trial. Mr. Blakesley QC described the First Defendant’s position as being, in the circumstances, a “barely permissible collateral attack on the jury’s finding in the criminal trial.” Ms Symington went further, arguing that the Court “must conclude that Mr. Wylecial (and thereby [RSA]) are liable for the injuries to all the Claimants.”

- Mr. Ferris on behalf of the First Defendant responded that the jury at the criminal trial had not had the benefit of all the evidence on the issue of causation (including that of four separate experts) which was to be led at the civil trial, and that it was open to him to prove that the chain of causation had been broken. Mr. Ferris was right in saying that, in my judgment. However, as outlined below, Mr. Ferris abandoned the novus actus argument by the time of the closing submissions. He accepted that Mr. Wylecial’s negligence caused, in part, all the relevant collisions and the resulting injuries. Instead, he was content to rest the First Defendant’s case on the footing that Mr. Martini and Mr. Mason were also negligent and played a causative part in the injuries sustained by the Claimants.

The course of the trial

- There were 5 parties separately represented by counsel at the trial before me, those being: Mr. Martini; Ms Zeqo; and the insurers for Mr. Wylecial, Mr. Martini, and Mr. Mason (RSA, SRI, and AXA respectively).

- Oral evidence was given by 2 witnesses of fact, namely Mr. Martini and Ms Zeqo. Mr. Martini was a forthright witness who did his best to assist the Court. Ms Zeqo found the process of giving evidence challenging, and said so, but her testimony was nonetheless similarly clear and helpful.

- There were also 4 collision investigation experts who attended trial and were cross-examined in turn. They were:

i) Mr. David Iwan Parry of the Transport Research Laboratory, instructed on behalf of the First Claimant;

ii) Mr. Paul Tydeman of CompassAI, instructed on behalf of the First Defendant. He also gave evidence on behalf of Mr. Wylecial at the criminal trial;

iii) Mr. Peter Davey of Viewpoint Investigation Services Ltd., instructed on behalf of the Second Defendant; and

iv) Mr. David Land of Collision Consulting (UK) Ltd., instructed on behalf of the Third Defendant.

- Each of the 4 experts was straightforward and impressive in the evidence that they gave. They were genuinely co-operative, and courteous about each other’s opinions where there were differences. Mr. Parry was examined first, and for significantly longer than the other experts.

The issues to be determined, following the close of evidence

- As mentioned at paragraph 45 above, Mr. Ferris confirmed, following the close of evidence, that he did not intend to pursue the novus actus point, i.e., the argument that the negligent driving of his client’s insured, Mr. Wylecial, was not a legal cause of any damage and injuries that followed the first collision.

- Mr. Ferris’ refined case was simply that Mr. Martini and Mr. Mason were also negligent, and that the negligence of both of them played a causative part in the injuries sustained by the Claimants. He contended in the closing submissions that Mr. Wylecial, Mr. Martini and Mr. Mason were all negligent to the same or a similar degree, and that all should bear an equal share of the blame for the resultant impacts and damage.

- Mr. Ferris helpfully made two second-order concessions as well:

i) First, he clarified that he did not intend to pursue an argument that the stricken Fiat was displaying any lights, given the expert evidence that had been heard;

ii) Second, he clarified that he did not maintain that a warning triangle which had been placed on the roadside by the Mercedes driver after the accident was of any significant evidential value; nor did he propose to rely on evidence that the Mercedes driver at one stage was said to have been waving a high-visibility jacket to warn approaching drivers of the hazards on the carriageway.

- Each of those concessions was realistic, and responsibly made. I turn now to examine the question whether either Mr. Martini or Mr. Mason acted negligently, and if so the share of responsibility that they should bear for the damage and injuries sustained.

Analysis

Threshold observations on the law

- Mr. Ferris drew to my attention the comments of Master Davison in Stark v. Lyddon [2019] EWHC 2076 (QB), at [27], concerning the approach to take to issues of apportionment of liability in a road traffic accident case such as the present:

“I turn then to the apportionment of liability, which requires an assessment of the blameworthiness and causative potency of the negligence found against each motorist. Cases on apportionment formed the bulk of the authorities cited to me. But, as has been said many times before, this is an exercise which is exquisitely fact-sensitive and previous decisions are of limited assistance.”

- I fully accept that the exercise of apportionment of liability is highly fact-sensitive. But I nonetheless consider that there are two important legal principles to be borne in mind.

- The first of these principles was urged on me by each of Mr. Blakesley QC, Ms Symington and Mr. Higgins. It is the so-called “agony of the moment” principle. This is the simple point that the Court should not require the same standard of care from a party who is forced to exercise judgment in the agony of the moment as it may do from a party who reaches a decision without being subjected to such pressures. The principle is particularly relevant to keep in mind in a case where the Court is not only asked to assess the behaviour of parties who have had to make split-second decisions (which all parties other than the First Defendant say was essentially the situation in the present case), but also where - as in this case - the forensic process at the trial involves intensive scrutiny by accident reconstruction experts, who weigh up whether it would have been reasonable for a party to react to hazards seconds or even fractions of seconds sooner than they did.

- A number of sources of authority for the “agony of the moment” principle were cited to me. Two of them fall to be mentioned here. The first was Clerk & Lindsell on Torts (23rd edition, 2021, consolidated with text from the Supplement), at para 7-165:

“Acting in an emergency: Where the defendant’s conduct has occurred in the course of responding to an emergency this will be regarded as relevant to the objective standard of care required. All that is necessary in such a circumstance is that the conduct should not have been unreasonable, taking the exigencies of the particular situation into account.”

- The second is the decision of HHJ Saffman sitting as a Judge of the High Court in YYY, Aviva Insurance Ltd. V. ZZZ [2021] EWHC 632 (QB), at [56], in which the Court had to consider the actions of a party who had to exercise judgment in the agony of the moment:

“… it is clear that the conduct of the defendant cannot be judged with the benefit of hindsight or, in my view, having regard to nice calculations done by experts with the benefit of computer models and calculators. What matters is whether, having identified a potential hazard, the claimant has established that the steps taken by the defendant to mitigate it were not reasonable steps or a reasonable response even in the agony of the moment.”

- The second principle was drawn to my attention by Mr. Blakesley QC. It is the elementary but crucial point that assessing what is a relevant cause in law for the purposes of attributing tortious liability, in road traffic accident cases and more generally, is an exercise that requires the application of common sense. In Wright v. Lodge [1993] RTR 123 (CA), Staughton LJ stated as follows at p.132:

“…Causation depends on common sense and not on theoretical analysis by a philosopher or metaphysician … Not every cause ‘without which not’ or ‘but for’ is regarded as a relevant cause in law. The judge or jury must choose, by the application of common sense, the cause (or causes) to be regarded as relevant.”

Did Mr. Martini act negligently?

- It will be recalled that, immediately prior to his collisions with the Fiat and the Scania HGV, Mr. Martini was proceeding at 65-70mph in lane 3 in his Audi. Although Mr. Martini did not register it at the time, the Scania HGV was moving across the carriageway ahead of him, initially from lane 1 to lane 2. I agree with Mr. Ferris’s submission that it is likely that the Scania had its indicator light flashing, as well as displaying the usual range of side and running lights that vehicles behind it could see.

- In his written closing submissions, Mr. Ferris focused on this point. His line of argument ran as follows:

i) Mr. Martini could and should have seen the Scania much earlier - it was a large, lit lorry moving across towards him with its indicator on and slowing down to a speed that would be noticeable on a quiet motorway in the early hours of the morning.

ii) Whilst Mr Martini may not have appreciated that the Scania presented an immediate hazard (thus engaging his “PRT” [“perception response time”]) he ought to have noticed its movement, its indicator and deceleration and appreciated that something was happening so that he needed to keep an eye on it as a potential hazard (particularly as there was little else for him to look at, at that stage).

iii) Had he done so he would have been aware of its movement into his lane at an early stage - it would not have seemed to him as if it "fell from the sky". His PRT would have been at or toward the lower end of the agreed range of 0.8 to 1.6 seconds and lower than the average of 1.2 seconds.

iv) His response would then have been a more measured one requiring firm but not emergency braking enabling him to remain behind the Scania without colliding with it or any other vehicle. He would have had sufficient time to slow to remain safely behind it, affording him time to assess fully what was happening.

v) Instead, by reason of his failure to maintain a proper lookout (possibly because he was tired) he placed himself in a position where he needed to react as an emergency and was compelled to brake and swerve. Had he kept a proper lookout he would not have needed to do so.

vi) The swerve into lane 2 was probably blind. It was a risky and dangerous manoeuvre. Mr. Martini would not have been forced to undertake it had he not placed himself into a position of danger by failing to react sooner.

- The reference in paragraph 61iii) above to “PRT”, or “perception response time”, is to a term of art that was used by all the experts at the trial. In his main report, Mr. Davey described it (quoting a 2020 publication by Muttart, the developer of a sophisticated computer programme to assist in gauging PRT) as the time between the onset of an emergency situation and when a driver begins a measurable manoeuvre. Mr. Davey emphasised that “onset” refers to the time when a perception response time is triggered, which must not be confused with the time when a potential hazard may have been first visible. Mr. Parry, when giving oral evidence, emphasised the same point. Mr. Parry also underscored that factors such as “night, rain, and spray could all affect PRT”, and he cautioned that it was important not to treat Muttart’s Interactive Driver Response Research (IDRR) programme, despite its sophistication, as capable of yielding precise information applicable to all fact situations.

- In his oral closing submissions, Mr Ferris amplified his argument concerning Mr. Martini’s alleged negligence, by reference to estimates in the joint expert report that had been produced by all the experts ahead of the trial. Mr. Ferris argued that it would have been possible for Mr. Martini to have continued driving in lane 3, and to have reacted to the Scania moving in front of him simply by braking and reducing his speed down from about 70mph to reach the same speed as the Scania (i.e., about 30mph). Mr. Ferris submitted also that, if Mr. Martini had exercised reasonable care, then he ought to have noted the movement of the Scania HGV as a potential hazard even before the moment when it started to encroach on lane 3. That sensitization to the potential danger would have reduced Mr. Martini’s estimated PRT, which was triggered when the Scania actually started moving across into lane 3. It would have reduced the PRT to a figure below the central estimate of 1.2 seconds that the experts had used in their joint expert report.

- Mr. Ferris’ calculations were predicated on the basis that the Scania’s movement across into lane 3 were gradual rather than in the nature of an emergency swerve. On that basis, he submitted that Mr. Martini could safely have accomplished the braking procedure in lane 3 in merely 4.8 seconds (i.e. 1.2 seconds of perception response time, added to 3.6 seconds required to brake to 30mph from 70mph), when he had available fully around 7-8 seconds in which to do so.

- Despite the skill with which these submissions were advanced, I am unable to accept them:

i) As I have already explained, I find that it was likely that the movement of the Scania into lane 3 was rapid. It was probably a reaction to the Scania’s headlights having picked out the unlit stationary obstacle in lane 2 at a distance of only about 60m away.

ii) The movement of the Scania into lane 3, while it was continuing to slow down to around 30mph, would also have been unexpected. Such vehicles are generally prohibited from travelling in lane 3. I reject (i) Mr. Ferris’ submission that Mr. Martini should have appreciated that the Scania was a potential hazard to him even before it crossed into lane 3, and (ii) the inference he invited me to draw, that Mr. Martini’s perception response time (triggered once the Scania did start to cross into lane 3) should therefore reasonably be assumed to have been smaller than the central estimate of 1.2 seconds canvassed by the experts;

iii) Taking the analysis and the figures which are used in section 9 of the joint expert report (entitled “The opportunity each driver reasonably had to avoid each collision”), it might have taken a minimum of 3-4 seconds for the Scania to cross over from lane 2 to lane 3. There would then have been a limited further time during which the Scania was travelling in lane 3 before the Audi collided with it, perhaps only 2 seconds if the Scania lane change had been more in the nature of an emergency swerve. That would all have meant that Mr. Martini might realistically have had available as little as 5 seconds in total to react and avoid a collision. He will have been confronted with the need to make a decision about what to do in the agony of the moment.

iv) As mentioned at paragraph 64 above, the time that was actually needed for Mr. Martini to have decelerated in lane 3 from 70mph to 30mph (i.e. to reach the same speed as the Scania in front of him) under emergency braking conditions could have been around 4.8 seconds, according to the experts. It would also have been within the bounds of reasonableness, in my judgment, if the perception response time for Mr. Martini were placed at the higher end of the range given by the experts, reflecting the 85th percentile of drivers: this would have been 1.6 seconds rather than the central estimate of 1.2 seconds, and it would have meant that the overall time needed for Mr. Martini to carry out emergency braking in lane 3 would have been 5.2 seconds (i.e. 3.6 + 1.6 = 5.2). Yet, as I have outlined, there may well have been available to him only around 5 seconds in total before his vehicle would strike the Scania.

v) In summary, while I accept that it is possible - if one makes certain doubtful assumptions - that there might have been enough time for Mr. Martini to have remained in lane 3 and to have braked safely, it is in my judgment more likely that Mr. Martini could not have achieved this.

vi) In this context, moreover, Mr. Martini reacted to the unexpected movement of the Scania in front of him by taking an “agony of the moment” decision to steer from lane 3 into lane 2 as well as braking. As Mr. Davey put it in his oral evidence: “The margins are so close that for someone to brake and swerve when applying brakes may have been the safer option, from my point of view, I don’t have a problem with the fact that he braked and swerved.” In my judgment, it is not appropriate for the Court to engage in a fine-grained mathematical calculus, on the basis of imperfect information, doubtful assumptions, and with the benefit of hindsight, in order to assess the liability in negligence of the motorist in the present context. There is no sufficient basis for me to find negligence on Mr. Martini’s part.

vii) It is necessary also to mention the expert evidence of Mr. Land at this point, since he estimated that Mr. Martini ought to have been in a position to see for himself the rear of the unlit Fiat van in lane 2, either via illumination by the Scania’s headlights when Mr. Martini was still about 160m away, or via his own vehicle’s headlights at an estimated distance of around 60m once the Scania was no longer shielding the Fiat from his view. However, I do not consider that Mr. Martini, who will have been principally concentrating on driving safely ahead in his lane, was at fault for failing to pick out the unlit Fiat in lane 2 briefly in the headlights of the Scania. Nor do I consider that Mr. Martini was negligent in failing to notice the unlit stationary Fiat immediately before taking his “agony of the moment” decision to steer left to avoid the Scania, which had unexpectedly moved in front of him. As Mr. Higgins rightly brought out in cross-examination of Mr. Land, Mr. Martini’s sightline to the Fiat van may have been re-established only about 1.5 to 2 seconds before the Audi struck the Fiat.

viii) Mr. Davey aptly described, in his oral evidence, the predicament faced by Mr. Martini:

“Mr. Martini cannot see past the Scania. So a decision to swerve into lane 2 is based on not knowing what is there, but if he feared a crash because there was not enough time to brake, it was the option.”

- It is necessary to address two further points raised by Mr. Ferris in the closing submissions, concerning alleged negligence on the part of Mr. Martini.

i) It was submitted that Mr. Martini’s decision to go on foot to the hard shoulder with Ms Zeqo after his Audi had come to a stop was also wrongful, in that it was foreseeable that they were both at risk of being struck there. He described this as “a foreseeably dangerous place to be, even if it was the least dangerous place”. I reject this point without hesitation. First, as Mr. Blakesley QC pointed out, Mr. Martini and Ms Zeqo in fact went beyond the hard shoulder, to stand on the grass verge. Secondly, this is a classic situation where the application of common sense shows that even if the behaviour of Mr. Martini is treated as a “but for” cause of the subsequent accident when the Vauxhall spun off the road and struck him and Ms Zeqo, it is not a relevant cause in law. It was action reasonably taken to reduce the level of danger that both Mr. Martini and Ms Zeqo would otherwise have been exposed to, if they had remained sitting in the damaged Audi in the middle of the eastbound carriageway before dawn.

ii) Mr. Ferris drew an analogy between the indisputably negligent conduct of Mr. Wylecial, the driver of the Fiat van, and the conduct of Mr. Martini. He stated:

“Mr Martini ran into the back of a lorry that was slowing down in front of him. Whilst the circumstances are not identical, his negligence is similar (not identical) to that of Mr Wylecial who had also driven into the back of a slower moving lorry in front of him. Mr Martini will say that the Scania moved across in front of him and, whilst that is obviously correct, Mr Wylecial did not have the benefit of an indicator to alert him to the lorry in front of him, only the closing distance and tail lights.” I reject the suggestion that there is a relevant parallel between the behaviour of these two individuals. Mr. Wylecial fell asleep at the wheel and drove at speed into the rear of a lorry. Mr. Martini was confronted with the need to make a split-second decision in order to avoid a collision with a lorry that had unexpectedly entered the outside lane of the motorway travelling at a very low speed.”

- In conclusion, I reject the contention that Mr. Martini’s driving was negligent, and that he therefore should bear a share of the responsibility for the series of collisions caused by Mr. Wylecial. I turn to consider the situation of Mr. Mason.

Did Mr. Mason act negligently?

- Mr. Mason did not give oral evidence at the trial. He filed a brief witness statement, the contents of which were agreed. In it, he explained that the last thing he remembered was passing Maidstone Services, before the time of the accident. It appears that his injuries from the collision between his vehicle and the Fiat were so serious that he was rendered unconscious for several minutes, after being in extreme pain, and he has no further recollections of the relevant events. It is therefore necessary to analyse what must have happened using indirect and circumstantial evidence only.

- The Kent Police incident report log for the day of the accidents was in evidence. The log recorded that an informant had called at 4:42am to report that there had been a three-vehicle road traffic collision, that there was a van sideways-on across lanes 1 and 2, and that the vehicles were not visible because the relevant part of the motorway did not have lights. Accordingly, the first collision (Fiat van/Mercedes HGV) had taken place by this time. A witness statement from PC Swallow, one of the police officers who attended the scene and gave evidence at the criminal trial, reports that “From the time recorded on the Mercedes tachograph and the first call recorded by Kent Police this collision occurred at 04:40 hours.”

- There appears to have been at least one further call made in the next minutes (timed at 4:45am). This reported that all persons appeared to be out of vehicles, there was a van sideways in the middle lane, and an articulated vehicle in the hard shoulder.

- Then, at 4:46am, the log records a call from Mr. James Hendrick, the driver of the Ford van following behind Mr. Mason in the Vauxhall Vivaro. The log reads: “Call from James Hendric [sic] …stating there maybe a car down the bank but this cannot be confirmed as of yet…”.

- Piecing this information together, it suggests that the final collision involving Mr. Mason’s Vauxhall occurred roughly 6 minutes after the first collision. It was at one point suggested by Mr. Ferris that this gap in time was relevant to the issue of negligence by Mr. Mason, because the likelihood was that, in the time between the first and fourth collisions, other vehicles will have passed through the accident scene on the eastbound carriageway without mishap, thereby raising the inference that Mr. Mason had not exercised reasonable care when he collided with the Fiat.

- I treat this as a consideration having very little weight: with one exception, mentioned immediately below, it is impossible to know which other vehicles (if any) traversed the accident scene, the way in which they proceeded, or indeed anything else about such other traffic. It is not even possible to deduce from the police call log that the calls which were received by Kent Police ahead of Mr. Hendrick’s call were made by the occupants of vehicles who had safely traversed the accident scene on the eastbound carriageway.

- The single exception is the lorry that Mr. Martini referred to in his written and oral evidence, as having very slowly travelled along lane 1 at the time when he and Ms Zeqo were walking over to the grass verge. That lorry cannot sensibly be taken as a benchmark for the standard of care to be exercised by Mr. Mason: most obviously, it may have been travelling consistently at a low speed in lane 1 in the first place; its driver may have him/herself perceived the collisions involving the Vauxhall and the Scania and Fiat van, or may have perceived the Scania moving across to park itself afterwards. In short, no inferences fall to be drawn from this about the standard of Mr. Mason’s driving.

- What is known is that, as Mr. Mason approached the scene in the Vauxhall Vivaro, there will have been certain lights flashing on vehicles that had already been involved in the first to third collisions. In this regard, Ms Symington on behalf of the Second Defendant (Mr. Mason’s insurers) explored in impressive forensic detail with the experts Mr. Parry and Mr. Tydeman what would have been visible to approaching traffic. It was established to my satisfaction that:

i) there was no indication that the Scania ever turned on its hazard warning lights, when parked. When the Scania was situated on the hard shoulder, any light it displayed would have been masked to approaching vehicles by the Mercedes behind it.

ii) it was likely that, on his approach, Mr. Mason’s sightline would have meant that he was able to pick out the following lights:

a) the nearside tail and indicator light on the Mercedes HGV, on the hard shoulder (but jutting into lane 1 - see Picture 2 above). This would have appeared to be indicating left;

b) the rear nearside hazard warning light of the stationary Audi, proximate to the lane-line of lane 1.

- These lights would have been visible around 500m before Mr. Mason reached the accident scene. However, as Mr. Tydeman said in the course of re-examination by Mr. Ferris: “At night, determining where the light source is is difficult. There is no other frame of reference. This changes as one approaches. It becomes possible to tell the relative distances between the two lights…”.

- Mr. Hendrick, who was driving along behind Mr. Mason on his approach to the accident scene, gave evidence at the criminal trial describing what he could see. He said that, at around 200/300m distance from the accident scene, he saw hazard lights. He said: “…something made me think that they weren’t slight - on the hard shoulder; there was something odd about it. At the time, I just instantly pulled into lane two just to give the - whatever it was a wide berth.”

- Mr. Hendrick’s evidence was that, on the approach to the accident scene, Mr. Mason moved from lane 1 into lane 2 and then collided with the unlit Fiat van. As indicated at paragraph 32 above, Mr. Hendrick’s account was that he himself was not aware of the presence of the Fiat until Mr. Mason struck it and but for that impact, he too would have struck it. In the course of cross-examination by Ms Symington, the expert Mr. Land agreed with the suggestion that Mr. Hendrick was in the best position to give an account of what could be seen on the road ahead by Mr. Mason.

- Within this context, the case mounted by Mr. Ferris in his closing written and oral submissions that Mr. Mason drove negligently involved the following main elements:

i) Mr Mason had a very early view of the potential hazard ahead of him, from 550 metres away. At 70 mph, it would have taken him nearly 17.5 seconds to close the gap. That was more than enough time to take steps to appreciate fully what was happening ahead and respond.

ii) That was particularly so given that Mr Mason's view of the potential hazard would have changed and improved as he drove closer to it. The lateral gap between the hazard lights would have become ever more apparent making the potential hazard ever more obvious. He should have seen the hazard warning lights, recognised them as such and responded, not as an emergency but as a precaution.

iii) There was sufficient time and distance for Mr Mason to have taken steps which would have avoided a collision. Mr. Ferris submitted that, when Mr. Mason was (at least) around 200m away from the accident scene, he should have taken one or more precautionary steps. These were:

a) using his main beam for a moment to identify what was ahead of him;

b) slowing down;

c) moving into lane 2 and then into lane 3; or

d) remaining in lane 1, at a lower speed if necessary.

iv) Consistently with this, the experts stated in the joint expert report: “If Mr. Mason had observed the lights ahead of him and responded with actions such as: slowing as a precaution, moving into lane 2 (or lane 3) and illuminating his high beam headlights to briefly gain an improved view of the road ahead, then we agree that he would have significantly improved his chances of avoiding a collision.”

v) There was sufficient room in lane 1 to have enabled Mr Mason to pass through the locus without a collision (as at least one large lorry had managed to do). That was particularly so had he been travelling at a lower speed (which should have been the case).

- I do not find these arguments persuasive, and I reject them:

i) There is no sufficient basis for finding that Mr. Mason’s failure to slow down significantly, in response to seeing the two flashing lights ahead from parked vehicles, was negligent. Based on the account of Mr. Hendrick, who had a good vantage-point from which to assess the scene, the two lights might well have appeared to be on the hard shoulder, or affecting lane 1. It would have been a reasonable response for Mr. Mason to move into lane 2 in order to give a wide berth to “whatever it was”, as he did.

ii) It is not appropriate to find that Mr. Mason failed reasonably to switch on his main beams, in order to survey the road ahead. I accept the point made by the expert Mr. Davey, that if there were oncoming vehicles at the time, then Mr. Mason may not have been in a position to illuminate his main beams.

iii) There are no good grounds for finding that Mr. Mason ought reasonably to have moved from lane 1 into lane 2 (from where, according to Mr. Ferris’ argument, he could subsequently have moved across further into the safety of lane 3) earlier than he actually did.

iv) Although it was possible for a vehicle to have navigated along lane 1 through the obstacles presented by, respectively, the Mercedes HGV (jutting into lane 1 from the hard shoulder) and the Audi (jutting into lane 1 from lane 2), and although the opinion of the expert Mr. Land was that this might have been achieved safely even if travelling at a relatively high speed of 65-70 mph, Mr. Mason’s decision to move into lane 2 when he did so - most likely in order to give a wide berth to perceived objects in the hard shoulder or lane 1 - cannot be classified as negligent.

v) As the experts stated in the joint expert report:

“We agree that if Mr. Mason was manoeuvring to avoid a perceived hazard ahead then his PRT range when unexpectedly encountering the stationary Fiat is likely to have been such that once Mr. Mason committed to the movement towards and into lane 2 the collision with the Fiat may have been unavoidable.”

- In all the circumstances, I reject the case that Mr. Mason acted negligently, and that negligence on his part was a cause of the damage and injuries sustained by the other Claimants or himself.

Conclusion

- For all the above reasons, I find that the negligent driving of Mr. Wylecial was the sole relevant cause of the damage and injuries sustained by the Claimants in these cases. I do not reach any finding that either Mr. Martini or Mr. Mason acted negligently. Accordingly, no questions of apportionment of liability arise.

- Counsel are invited to draw up a draft minute of order reflecting my conclusions in this judgment.