�

SERCO LTD AGAINST FORTH HEALTH LTD [2020] ScotCS CSOH_48 (20 May 2020)

BAILII is celebrating 24 years of free online access to the law! Would you

consider making a contribution?

No donation is too small. If every visitor before 31 December gives just £1, it

will have a significant impact on BAILII's ability to continue providing free

access to the law.

Thank you very much for your support!

[New search]

[Printable PDF version]

[Help]

Page 1 ⇓

OUTER HOUSE, COURT OF SESSION

[2020] CSOH 48

CA91/19

OPINION OF LORD ERICHT

In the cause

SERCO LIMITED

against

FORTH HEALTH LIMITED

Pursuer

Defender

20 May 2020

Pursuer: Cormack QC, solicitor advocate; Pinsent Masons LLP

Defender: Richardson QC; Harper Macleod LLP

Introduction

[1] Forth Valley Royal Hospital is a modern hospital constructed under the Private

Finance Initiative (“PFI”). The defender is the special purpose vehicle set up to design, build

and operate the hospital. The pursuer supplies certain services to the defender under a

Facilities Management Agreement. That agreement runs to March 2042 and makes

provision for payments due to the pursuer over that period to be adjusted in certain ways to

allow for inflation and other changes in costs. In particular, it makes special provision for

“wage drift.” Wage drift occurs when wages increase at a higher level than inflation. The

parties are in dispute as to certain wage drift provisions. The pursuer claims that on a

Page 2 ⇓

2

correct interpretation of these provisions the pursuer remains entitled to payment for wage

drift of £163,553.75 a month. The defender claims that on a correct interpretation of the

wage drift provisions, entitlement to a wage drift uplift ceased on the seventh anniversary of

the contract and the pursuer is no longer entitled to such payments. The dispute between

the parties as to interpretation turns on the meaning of the term “First Market Test Date”.

That term is not expressly defined in the agreement. The pursuer also pleads an alternative

case arising out of the defender’s participation in a review of the payments at the seventh

anniversary conducted by way of a Benchmarking Exercise.

[2] The case called before me for debate at which the defender sought dismissal of both

the pursuer’s primary case on interpretation and the pursuer’s alternative case on the

Benchmarking Exercise.

The contractual structure

[3] On 4 May 2007 the defender entered into a contract with Forth Valley Health Board

(the “Project Agreement”). On 14 May 2007 the pursuer and the defender entered into the

Facilities Management Agreement. The contractual provisions followed the standard

pattern, known to and accepted by the market, for arrangements entered into under the

Private Finance Initiative whereby monies due in connection with the services flowed from

the Board to the defender and then from the defender to the pursuer. The services to which

this dispute pertains were provided by the pursuer for the Board in the hospital. In

accordance with standard practice in respect of PFI contracts, the Board pays a Unitary

Charge to the defender under the Project Agreement. The Unitary Charge encompasses the

construction, financing and operation of the hospital for the contractual term which expires

on 31 March 2042. Under the Facilities Management Agreement, the pursuer provides

Page 3 ⇓

3

certain services to maintain and operate the hospital, which in turn enables the defender to

implement the relevant obligations under the Project Agreement. While the Project

Agreement and the Facilities Management Agreement have different mechanisms by which

payments are calculated, those mechanisms were designed to operate in a coherent manner.

A Financial Model was drawn up as part of the contract process.

The formula for the annual payment to the pursuer under the Facilities Management

Agreement

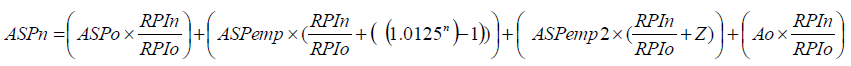

[4] The annual payment by the defender to the pursuer is governed by an algebraic

formula set out in Part 18 of the Schedule to the Facilities Management Agreement at

section B paragraph 2.1 as follows:

"2.1 The annual FM Service Payment for any Contract Year shall be calculated in

accordance with the following formula:

where:

2.1.1 ASPn is the Annual FM Service Payment for the relevant Contract Year;

2.1.2 ASPo is £[figure], being that part of the Annual FM Service Payment at the

Base Date that relates to that part of the service payment which does not relate to

employment costs, subject to paragraph 2.2 (Annual FM Service Payment) of this

Section B of this Part 18 of the Schedule (Payment Mechanism);

2.1.3 ASPemp is £[figure], being that part of the Annual FM Service Payment at the

Base Date that relates to the employment costs in connection with the provision of

the Services excluding ASPemp2, subject to paragraph 2.2 (Annual FM Service

Payment) of this Section B of this Part 18 of the Schedule (Payment Mechanism);

2.1.4 ASPemp2 is £[figure], being that part of the Annual FM Service Payment at

the Base Date that relates to the employment costs in connection with the provision

of the Market Tested Services, subject to paragraph 2.2 (Annual FM Service Payment)

of this Section B of this Part 18 of the Schedule (Payment Mechanism);

Page 4 ⇓

4

2.1.5 Ao is that part of the Annual FM Service Payment that relates to the Market

Tested Services following Market Testing in accordance with paragraph 3 (Effect of

Market Testing on Annual FM Service Payment), subject to paragraph 2.2 (Annual

FM Service Payment) of this Section B of this Part 18 of the Schedule (Payment

Mechanism);

2.1.6 n is the number of expired years from the Base Date to the commencement of

the relevant Contract Year where a year is a period of twelve calendar months

commencing on the Base Date and each anniversary thereof;

2.1.7 Z is

(a) for the period until the First Market Test Date ((1.0125n)-1)where n has

the meaning defined in paragraph 2.1.6; and

(b) for the period after the First Market Test Date nil.

2.1.8 RPIn is the value of the RPI published or determined with respect to the

month of February which most recently precedes the relevant Contract Year; and

2.1.9 RPIo is the value of the RPI published or determined with respect to the

Indexation Base Month.”

[5] The "Annual Service Payment" is defined in Part 18 of the Schedule to the Contract at

section A as:

"the sum in pounds sterling calculated in accordance with the provisions set out in

Section B paragraph 2 (Annual FM Service payment) of this Part 18 of the Schedule."

[6] "Market Tested Services" is defined in Part 17 of the Schedule to the Contract as:

"those services descried in sections 04 (Ward Housekeeping), 07 (Waste

Management), 10 (Domestic), 11 (Reception), 12 (Portering), 13 (Linen) and

15 (Switchboard) of Section 1 of Part 14 of the Schedule (Service Requirements) and

any other Service from time to time designated as such by the parties."

[7] "Market Testing" is defined in Part 17 of the Schedule to the Contract as:

"the process (excluding the Benchmarking Exercise) described in this Part 17 of the

Schedule (Benchmarking and Market Testing Procedure) and the term ‘Market

Tested’ and ‘Market Test’ shall be construed accordingly."

[8] There is no definition of “Market Test Date.”

[9] "Market Testing Date" is defined in Part 17 of the Schedule to the Contract as:

Page 5 ⇓

5

"every seventh anniversary of the Actual Completion Date during the Project Term."

[10] The Actual Completion Date was 18 April 2011.

Benchmarking and Market Testing

[11] The Project Agreement and the Facilities Management Agreement include provisions

for review of the payments after 7 years. These provisions are complex and, so far as

relevant to this case, can be briefly summarised in a much simplified form as follows. A

Benchmarking Exercise may be carried out. The purpose of the Benchmarking Exercise is to

ascertain the relative costs and competiveness of certain services and it does so by

comparing the standards and prices of the particular service with the costs and prices of

equivalent services provided to other hospitals operating under PFI. The Benchmarking

Exercise will, in some circumstances, be the end of the review process. However, in other

circumstances, eg where the cost of the particular service is found to be in excess of 105% of

market costs, then a Market Testing process takes place. Market Testing involves going out

to the market place and obtaining tenders for the provision of the particular service. A

company tendering for the work will base its tender on the actual wage costs in the market

at the time of the tender. Accordingly, the wage costs used in the Market Testing are the

actual wage costs around the seventh anniversary, and are not based on an estimate of wage

costs calculated by applying a formula for inflation and wage drift over the previous 7 years.

The pursuer’s case on interpretation of the Contract

Defenders submissions

[12] Senior Counsel for the defender submitted that the defender’s contractual case was

irrelevant because, in terms of the Contract, after 18 April 2018 (being the seventh

Page 6 ⇓

6

anniversary of the Actual Completion Date) “Z” had a value of nil and the pursuer no

longer had any entitlement to any payment in respect of the “Z” factor. The critical question

was the date from which Z reduced to nil in terms of paragraph 2.1.7(b) and, therefore, what

did the parties intend by the term “First Market Test Date”. The phrase “First Market Test

Date” was not defined. However it should be construed in accordance with its natural

meaning and the definitions of “Market Testing Date” to mean the seventh anniversary of

the Actual Completion Date. This gave the natural meaning to the words the parties used.

It was inherently unlikely that if the parties had intended “Market Test Date” to mean

something completely different from “Market Testing Date”, they would have chosen such

very similar language for the two phrases.

[13] Counsel further submitted that his construction of the phrase “First Market Test

Date” made commercial sense in that:

(a) it provided certainty as to the point at which the “Z” factor was to be reduced

to nil. The process of Market Testing was a relatively complicated process which

takes place over a lengthy period. It is commercially improbable that the parties

would have intended there to be uncertainty as to the point at which the “Z” factor

was to be reduced to nil; and

(b) the inclusion of the “Z” factor as an addition to the sums paid to the pursuer

in respect of the Market Tested Services was intended to mitigate the risk of wage

drift. If benchmarking showed wage drift beyond the stipulated tolerance of 95%

to 105% of the Market Costs, this would be corrected going forward by the carrying

out of Market Testing. If, on the other hand, the Benchmarking Exercise were to

establish that the Latest Service Element fell within the contractual tolerance and that

the prices of the Market Tested Services (excluding the Z factor) were therefore

Page 7 ⇓

7

broadly in line with the market, there would be no commercial reason for the

Z factor to continue beyond the first Market Testing Date: otherwise there would be

a commercially nonsensical result that, where the Benchmarking Exercise established

that costs of the Market Tested Services (without the Z factor) were in keeping with

market prices, the pursuer would nonetheless be entitled to be paid the “Z” factor

into the future at a rate which increased on an annual basis, thus rendering the

pursuer's pricing more and more out of step with market rates each year.

Pursuer’s submissions

[14] Senior solicitor advocate for the pursuer invited me to allow proof before answer,

with all pleas standing. He submitted that it could not be said that the pursuer’s case was

bound to fail (Jamieson v Jamieson 1952 SC (HL) 44). The Facilities Management Agreement

was ambiguous. The words “First Market Test Date” in the definition of Z were not a

defined term. The pursuer was wrong to say that these words meant the same as the

defined terms “First Market Testing Date.” The correct interpretation was that “Market

Test” meant an actual instance of carrying out the process of Market Testing. As there were

two possible constructions, the court was entitled to prefer the one which was consistent

with business common sense (Wood v Capita Insurance Services [2017] UKSC 24 at

paragraph 13) and should not attribute too legalistic a meaning (Ardmair Bay Holdings Ltd v

Craig [2019] CSOH 58 at paragraph 133). The definition of Z had not been drafted with

scrupulous care (HOE International Ltd v Anderson 2017 SC 313 at paragraph 23).

[15] The solicitor advocate further submitted that the pursuer’s construction was the

more natural meaning of the words. It was inherently unlikely that parties would choose to

apply a provision for wage drift to one category of services (which are not market tested)

Page 8 ⇓

8

but end provision for wage drift for another category of services (which are market tested)

after 7 years. It made sense for Z to fall to zero at the point where a Market Test actually did

take place, as wage drift would be taken into account in the bids made. Further, Ao only

applies after Market Testing and would expect to include the whole extent of wage increases

from the start of the contract to the bidding. Further, it would distort the Benchmarking

Exercise to ascribe a nil value to Z: the defender’s interpretation would entail that like was

not compared with like. He further submitted that the defender’s argument founded on the

definition of “index linked” was very weak as that definition does not apply where the

context otherwise requires. He further submitted that it was inherently unlikely that the

parties intended the defender to gain a windfall benefit.

[16] In conclusion, he submitted that the court required to hear evidence about the import

of the Financial Model, and also of matters of commercial background founded on in the

pursuer’s averments but disputed by the defender.

Discussion and decision

[17] The dispute between the parties turns on the meaning of the term “First Market Test

Date” in paragraph 2.1.7 of the Facilities Management Agreement. That term is not defined

in the agreement.

[18] The pursuer says that the term means the first time that a market test is conducted.

The practical effect of this interpretation is that, as no market test has been conducted, the

uplift for wage drift continues to have effect.

[19] The defender says that the term is a reference to the “Market Testing Date” which is

defined in section 1 of Part 17 of the Schedule and occurs on the seventh anniversary of the

Page 9 ⇓

9

contract. The practical effect of this interpretation is that after that anniversary on 18 April

2018, the uplift for wage drift was reduced to zero.

[20] The question for me at this stage is whether the pursuer is bound to fail (Jamieson v

Jamieson).

[21] In the absence of any definition of the term, the interpretation offered by the pursuer

is a possible one. The pursuer has averred a reasoned case as to why he says his

interpretation is the correct one. In summary the pursuer’s position is that the wage drift

uplift is not required after Market Testing, as wage increases are taken into account as part

of the Market Testing process. The pursuer says that where there is no Market Testing, it

makes commercial common sense for wage drift provision to continue to apply rather than

being arbitrarily terminated after 7 years. The pursuer says that the effect of the defender’s

interpretation on the PFI payment structure as a whole would be that the Board would

continue to pay the defender as before but the defender would make reduced payments to

the pursuer and retain the wage drift element: such a windfall would not make commercial

common sense. The pursuer’s averments refer to the complex contractual structure of this

PFI project taken as a whole, and the economic factors and financial modelling which

underpin that structure.

[22] Taking the pursuer’s averments pro veritate, as I am bound to do for the purposes of

debate, I find that the pursuer is not bound to fail.

[23] This is a case where, despite being professionally drafted, a contractual term is

ambiguous and both parties have proffered possible interpretations of it. The contract forms

part of a complex contractual and economic structure for a Private Finance Initiative project.

The pursuer offers to lead evidence about the standard pattern for contractual provisions in

Page 10 ⇓

10

PFI contracts. The words of Lord Hodge at para [13] of Woods Capita are particularly

apposite to this case:

“But negotiators of complex formal contracts may often not achieve a logical and

coherent text because of, for example, the conflicting aims of the parties, failures of

communication, differing drafting practices, or deadlines which require the parties to

compromise in order to reach agreement. There may often therefore be provisions in

a detailed professionally drawn contract which lack clarity and the lawyer or judge

in interpreting such provisions may be particularly helped by considering the factual

matrix and the purpose of similar provisions in contracts of the same type.”

[24] In determining this case it will be important to consider the factual matrix and the

purpose of provisions in PFI contracts. The pleadings disclose material differences between

the parties as to important aspects of the factual matrix, such as the Financial Model and the

interrelationship between the payment provisions under different contracts within the

overall PFI project. In my view this case cannot properly be determined without evidence.

The pursuer’s alternative case based on the Benchmarking Exercise

[25] A Benchmarking Exercise took place around 2017. In article 5 of condescendence the

pursuer makes detailed averments about the exercise, which include the following. The

pursuer avers that the figures from Forth Valley Royal Hospital used in the Benchmarking

Exercise for comparison with the other comparator hospitals included the wage drift uplift.

The pursuer also avers that the defender did not object to this, and that “the defender

consented, either expressly or by necessary implication from its continued participation in

Benchmarking without objection, to the use of the figures in this way”. The pursuer avers:

“At the conclusion of the benchmarking process, on or around July 2017, agreement

was reached with the Board (and thus under the contractual structure between the

Board and the Defender and the Defender and the Pursuer) that there would be ‘no

change’ to the Annual Service Payment to the Pursuer. That was confirmed in letters

of 4 and 10 July 2017. On a proper construction, this agreement, which was binding

on parties, meant that there would be no change to the Pursuer's actual rates which

had been Benchmarked on which basis the provisions of the Contract would

Page 11 ⇓

11

continue to apply. This in turn meant that (a) the accumulated effect of the

application of limb (a) of Z would continue to be charged; and (b) that further

increases as a result of the application of that limb would be applied in due course. "

[26] Consequential to these averments, the pursuer avers in article 7:

“Further and in any event, the making by the Defender of the deductions

complained of is inconsistent with the binding agreement reached between parties in

the Benchmarking Exercise which was undertaken as set out above. As a matter of

contract or, alternatively as a matter of the operation of personal bar in the

circumstances, the Defender is not entitled to adopt a position different to that which

was reached in that Exercise as the Defender seeks wrongfully to do in making the

deductions complained of. For the Defender to be permitted to change position in

such a manner would plainly result in unfairness to the Pursuer as it would alter the

basis upon which the Exercise was objectively conducted and concluded in a manner

which would cause material loss to the Pursuer reflected in a material and wholly

unjustified gain to the Defender.”

[27] The letter of 4 July 2017 was from the Board to the defender. It states:

“Forth Valley Royal Hospital PPP

Benchmarking Exercise 2017

As you will be aware the Benchmarking exercise of Soft FM Services as required by

Part 17 of the PA was considered by NHS Forth Valley Performance and Resources

Committee on 27th June 2017. I am pleased to inform you that the committee agreed

with the results of the benchmarking exercise and not to proceed to market testing.

The Committee also acknowledged the quality of service provided by Serco and the

good partnership working that exists between the Board, Forth Health and Serco.

NHS Forth Valley recognises the impact of the housekeeping service on catering

costs resulting in catering costs at Forth Valley Royal Hospital sitting out with 95%

and 105% of the Scottish PFI market rate and agrees that Clause 1.1.4 of Part 17 of the

PA applies with no change required to the Annual Service Payment.

I now look forward to working with you and Serco to review the Service

Improvement proposals identified.”

[28] The letter of 10 July 2017 was from the defender to the pursuer. It states:

“Forth Valley Royal Hospital PPP

2017 Benchmarking Exercise

I refer to my email dated 5th July 2017 enclosing a copy of the letter received from

NHSFV dated 4th July 2017 regarding the 2017 Benchmarking Exercise.

Page 12 ⇓

12

I can confirm, as stated in NHSFV's letter, that the 2017 Benchmarking exercise has

been accepted and that we will not be required to undertake a Market Test.

As we are not undertaking a Market Test the requirements stated in Clauses 3.1, 3.2

and 5.1 of Part 17 of the Schedule to the Facilities Management Agreement will not

apply in this instance.”

[29] Clause 58 of the Facilities Management Agreement states:

“AMENDMENTS

This Agreement may not be varied except by an agreement in writing signed by duly

authorised representatives of the parties.”

Defender’s submissions

[30] Senior Counsel for the defender invited me to dismiss the pursuer’s alternative case

by deleting article 5 in its entirety and the passage from article 7 quoted above.

[31] Counsel submitted the pursuer based its alternative case on an agreement concluded

and confirmed in the letters dated 4 and 10 July 2017, but that agreement was not capable of

supporting the pursuer’s argument. These two letters founded upon by the pursuer made

clear that the agreement related solely to the issue of whether, following the Benchmarking

Exercise, Market Testing was required in circumstances where the Latest Service Element for

one of the Market Tested Services (Patient Catering) had been found to be in excess of 105%

of Market Costs. However, they contain no agreement concerning either the amount of the

Annual FM Service Payment or the “Z” factor. The letter dated 4 July 2017 was addressed to

the Board not the pursuer and related not to the Contract but to the Project Agreement

between the Board and the defender. The letter dated 10 July 2017, said nothing as to the

amount of the Annual FM Service Payment.

[32] Counsel further submitted that the alternative case fell to be tested on the basis that

the defender is correct as to the proper construction of the Contract. Otherwise, it adds

nothing to the pursuer’ contractual case which has been addressed above. The pursuer’s

Page 13 ⇓

13

position was that notwithstanding that the Contract required the “Z” factor to be reduced to

nil after 18 April 2018 (being the seventh anniversary of the Actual Completion Date), the

parties had agreed to amend the Contract to the effect that the “Z” factor is to continue to an

unspecified date. This position was not sustainable on the basis of the letters founded upon.

[33] Counsel further submitted that it was not clear from the pursuer’s averments what, if

anything, the pursuer is said to have done, to its prejudice to support the plea of personal

bar. As such, the pursuer’s averments did not appear to be sufficiently specific to displace

the effect of clause 58 (see MWB Business Exchange Ltd v Rock Advertising Ltd [2018] UKSC 24

at para [16]).

Pursuer’s submissions

[34] Senior Solicitor Advocate for the pursuer submitted that the defender’s position was

that the legal outcome of a process in which the rates which were benchmarked including

wage drift was that the rates which applied after that benchmarking excluded wage drift. It

did not make sense to include an element in the price which is to be benchmarked, if that

element was to be removed if the outcome of the Benchmarking was that Market Testing

was not to take place. The court should hear evidence on this. The letters on which the

pursuer founded had been taken out of context. Evidence of the context was required.

[35] Senior Solicitor Advocate further submitted that the pursuer’s case was not bound to

fail. Properly construed, the letters were an agreement that there would be no change to the

pursuer’s actual rates which had been benchmarked. The agreement was consistent with

the Facilities Management Agreement and not a variation of it. He further submitted that

the pursuer’s argument on personal bar was founded on English law (MWB Business

Exchange Ltd v Rock Advertising Limited), and did not take account of William Grant & Sons v

Page 14 ⇓

14

Glen Catrin Bonded Warehouse Limited 2001 SC 901 at paragraph 33 and Kabab-ji Sal

Discussion and decision

[36] In his alternative case, the pursuer founds on the Benchmarking Exercise in which

both the pursuer and the defender participated in 2017. As this is an alternative case, it

proceeds on the basis that the pursuer is unsuccessful in his primary case on interpretation.

In essence, the point the pursuer seeks to make is that the 2017 Benchmarking Exercise

proceeded on the basis that the wage drift provision would continue to apply: the

defender’s position in the Benchmarking Exercise was compatible with the pursuer’s

interpretation of the wage drift provision and incompatible with the interpretation which

the defender is now advancing in this case. The defender’s averments disclose various

matters of factual dispute regarding the Benchmarking Exercise, but for present purposes I

take the pursuer’s averments pro veritate.

[37] Although the pursuer makes detailed averments about the Benchmarking Process

and the participation of the defender in it, the submissions for the defender focussed on the

two letters. The submissions criticised the letter of 4 July 2017 as not being between the

parties under the Facilities Management Agreement but being from the Board to the

defender under the Project Agreement. A further criticism was that the letters did not

conform to the procedure set out in clause 58 for variation of the Facilities Management

Agreement. However it seems to me that in making these criticisms the defender takes too

narrow a view of the pursuer’s alternative case. The pursuer’s averments as to the

participation in the Benchmarking process are wider than merely founding on the two

letters. The letter of 4 July 2017 needs to be read in the context of the pursuer’s averments as

Page 15 ⇓

15

to the interrelationship between the Project Agreement and the Facilities Management

Agreement. The letters need to be read in the context of the pursuer’s averments to the

effect that the defender consented to the 2017 Benchmarking Process being conducted on the

basis of the pursuer’s interpretation of the wage drift provisions. They also need to be read

in the context of the pursuer’s averments to the effect that the defender accepted the result of

the Benchmarking process. Taking the pursuer’s averments in the round, in my opinion

these criticisms are not such that the pursuer’s alternative case is bound to fail.

[38] The defender further argues that it is not clear from the pursuer’s averments what, if

anything, the pursuer is said to have done to its prejudice to support the plea of personal

bar. The defender says that as such, the pursuer’s averments are not sufficiently specific to

displace the effect of clause 58, which prohibits variation of the Facilities Management

Agreement other than by an agreement in writing signed by duly authorised representatives

of the parties.

[39] In considering that argument, the starting point must be the Scots law of personal

bar. This was set out by the Lord President in William Grant & Sons v Glen Catrin Bonded

Warehouse Limited:

“It was agreed, on both sides of the bar, that acquiescence is but one particular

example of the general doctrine of personal bar, which is an equitable doctrine,

and which, in my judgment, speaking generally, may come into play where the

law considers it inequitable that a man who has represented a state of facts and his

representation has induced another both to believe in this state of facts, and to

arrange his affairs as a result thereof, should be later allowed to go back on that

representation. I accept, as senior counsel for the reclaimers put it, that the equitable

basis of all pleas of personal bar is rooted in the notion that a litigant should not be

permitted to come to court and deny what he has previously affirmed. But, since the

effect of acquiescence may be to obliterate, for practical purposes, what are otherwise

perfectly valid and subsisting legal rights, the equities require, in my judgment, that,

if a person's rights are to be so obliterated, he has induced, in some way, others to

believe that he was no longer interested in enforcing his rights against them and that

they have altered their position in reliance on that belief. I prefer in this context to

use the expression 'altered their position' rather than the words 'acted to their

Page 16 ⇓

16

prejudice' since, it seems to me, that an analysis of the authorities, which were placed

before us, demonstrates that the doctrine may operate, provided reliance has been

placed on the representation, even though what may ordinarily be described as

prejudice to the party so relying has not occurred.” (para [4]) (emphasis added)

[40] In my opinion, taking the pursuer’s averments pro veritate, the pursuer has averred a

case which satisfies the requirements set out by the Lord President. The defender has

represented in the Benchmarking Exercise that the wage drift uplift continues to apply after

the seventh anniversary. The defender’s representation has induced the pursuer both to

believe in this state of facts, and to arrange his affairs as a result thereof by concluding the

Benchmarking Exercise on the basis of that representation. If the argument were to stop

there, my conclusion would be that the pursuer’s benchmarking case is not bound to fail.

[41] However, the defender’s argument is that we should not stop there and that

notwithstanding what is said by the Lord President, the pursuer’s case is bound to fail on

the basis of the English Supreme Court case of MWB Business Exchange Ltd v Rock Advertising

Limited.

[42] The issue in MWB Business Exchange Ltd v Rock Advertising Limited was whether a

contractual term prescribing that an agreement may not be amended save in writing signed

on behalf of the parties (commonly called a “No Oral Modification” clause) is legally

effective. In the course of his opinion, Lord Sumption commented on the application of the

English law of estoppel to a situation where a party acts on an oral variation despite there

being a No Oral Modification clause. He said at paragraph 16:

“The enforcement of No Oral Modification clauses carries with it the risk that a party

may act on the contract as varied, for example by performing it, and then find itself

unable to enforce it. It will be recalled that both the Vienna Convention and the

UNIDROIT model code qualify the principle that effect is given to No Oral

Modification clauses, by stating that a party may be precluded by his conduct from

relying on such a provision to the extent that the other party has relied (or

reasonably relied) on that conduct. In some legal systems this result would follow

from the concepts of contractual good faith or abuse of rights. In England, the

Page 17 ⇓

17

safeguard against injustice lies in the various doctrines of estoppel. This is not the

place to explore the circumstances in which a person can be estopped from relying

on a contractual provision laying down conditions for the formal validity of a

variation. The courts below rightly held that the minimal steps taken by Rock

Advertising were not enough to support any estoppel defences. I would merely

point out that the scope of estoppel cannot be so broad as to destroy the whole

advantage of certainty for which the parties stipulated when they agreed upon terms

including the No Oral Modification clause. At the very least, (i) there would have to

be some words or conduct unequivocally representing that the variation was valid

notwithstanding its informality; and (ii) something more would be required for this

purpose than the informal promise itself.”

[43] In Kabab-ji Sal (Lebanon) v Kout Food Group (Kuwait) the Court of Appeal applied these

dicta to a situation which:

“involves an unequivocal representation that the second floor does not have to be of

load-bearing capacity, upon which the contractor relies by building according to that

oral modification. In those circumstances, the school board could not rely upon the

No Oral Modification clause. The illustration is a classic example of what

Lord Sumption JSC said at [16] of his judgment was required by way of estoppel.“

(para 75])

[44] There is an obvious similarity between the situation in Kabab-ji Sal (Lebanon) and the

situation as averred by the pursuer in the current case. The pursuer has averred a case

which involves an unequivocal representation by the defender, as part of the Benchmarking

Process, that the wage drift uplift applies after the 7 year anniversary, upon which the

pursuer relies by concluding the Benchmarking Process according to that representation.

Even if the defender is correct to say that the law in Scotland is the same as in England, it

cannot, standing Kabab-ji Sal (Lebanon) v Kout Food Group (Kuwait), be said that the pursuer’s

case is bound to fail. In any event, the question of whether Scots law on personal bar is the

same as the English law of estoppel, and if so whether there is personal bar/estoppel on the

particular facts of this case, is best considered once evidence has been led and the facts of the

Benchmarking Exercise have been established.

Page 18 ⇓

18

Order

[45] I shall allow a proof before answer with all pleas standing. I reserve all questions of

expenses in the meantime.

BAILII:

Copyright Policy |

Disclaimers |

Privacy Policy |

Feedback |

Donate to BAILII

URL: http://www.bailii.org/scot/cases/ScotCS/2020/2020_CSOH_48.html