JTI ACQUISITION COMPANY (2011) LIMITED Revenue & Customs (CORPORTION TAX - whether non-trade loan relationship debits to be disallowed) [2022] UKFTT 166 (TC) (19 April 2022)

BAILII is celebrating 24 years of free online access to the law! Would you

consider making a contribution?

No donation is too small. If every visitor before 31 December gives just £1, it

will have a significant impact on BAILII's ability to continue providing free

access to the law.

Thank you very much for your support!

[New search]

[Contents list]

[Printable PDF version]

[Help]

Neutral Citation: [2022] UKFTT 166 (TC)

Case Number: TC 08493

FIRST-TIER TRIBUNAL

TAX CHAMBER

By remote video hearing

Appeal reference: TC/2019/04496

CORPORTION TAX - sections 441 and 442 CTA 2009 - whether non-trade loan relationship debits to be disallowed - UK company incorporated to be the holding company to acquire a US group by stock purchase - cross-jurisdiction intercompany loan between US parent and UK holding - whether the loan relationship had an ‘unallowable purpose’ - whether securing a ‘tax advantage’ was not the main or one of the main purposes - whether attribution on a just and reasonable basis - appeal dismissed

Heard on: 23 to 25 March 2021 followed by

written submissions on 6 and 16 April 2021

Judgment date: 19 April 2022

Before

TRIBUNAL JUDGE HEIDI POON

Between

|

|

JTI ACQUISITION COMPANY (2011) LIMITED |

Appellant |

|

|

- and –

|

|

|

|

THE COMMISSIONERS FOR HER MAJESTY’S REVENUE AND CUSTOMS |

Respondents |

Representation:

For the Appellant: John Gardiner QC, and Michael Ripley, of counsel, instructed by RPC LLP

For the Respondents: Elizabeth Wilson QC, instructed by the General Counsel and Solicitor to HM Revenue and Customs

DECISION

Introduction

-

1. JTI Acquisition Company (2011) Limited (‘the Appellant’) is a UK company, and at all material times was a member of a corporate group with its ultimate parent company in the US. The appeal concerns four closure notices issued by the respondents (‘HMRC’), which disallowed the Appellant’s claim of non-trade loan relationship debits in relation to four accounting periods ending 31 October 2012 to 2015 pursuant to section 441 of the Corporation Tax Act 2009 (‘CTA 2009’).

-

2. The interest debits on the borrowing claimed by the Appellant totalled £40,050,776, and the corporation tax at stake is approximately £9m.

Issues for determination

-

(1) Whether the main purpose, or one of the main purposes, for which the Appellant became party to the loan relationship with its immediate US parent company was to obtain a UK tax advantage for the purposes of sections 441 and 442 of CTA 2009; and

-

(2) If there was an unallowable purpose, what proportion of any relevant debit is attributable to that unallowable purpose.

Evidence

-

4. The hearing bundle of 524 pages contains 384 pages of documents (paginated 141 to 524) which were distilled by the respondents from some 17,000 documents (unindexed and unsorted)1 served on the Appellant’s behalf during the enquiry. These 384 pages of core documents represent the cohort of legal instruments in connection with the non-trade loan relationship, and the contemporaneous correspondence of the key personnel involved in structuring the financing scheme of which the non-trade loan relationship formed a part.

-

5. The rest of the hearing bundle comprises the parties’ pleadings, Tribunal Directions, the enquiry correspondence and closure notices, inter-partes correspondence, Mr Michael Olsen’s witness statement with exhibits, and three other affidavits. The authors of these affidavits (Krueger, Kulasa, Hodgetts) have not been called as witnesses for cross-examination; hence their statements have no status as evidence, and no reference is made thereto.

-

6. Mr Michael Olsen was the only witness called by the Appellant. From 2008 to 2012, Mr Olsen was Executive Vice President (EVP) and Chief Financial Officer (‘CFO’) of Joy Global Inc, which was the ultimate US parent of the Appellant. Mr Olsen was also group Treasurer from 2008 to 2011, and the US director of the Appellant from 8 June 2011 until 31 January 2013. Mr Olsen has since retired; he gave evidence as a former office-holder. Whilst parts of Mr Olsen’s evidence are helpful in understanding the operation and business of the group, I find that the material aspects of Mr Olsen’s testimony as respects the adoption of the acquisition and financing structure involving the Appellant represent an account of events given with the legal issues in mind. Consequently, I have accorded more weight to contemporaneous records, and the email exchanges at the material times amongst the key personnel. I consider the value of Mr Olsen’s oral evidence lies chiefly in the opportunity which cross-examination afforded, by subjecting the documentary evidence to critical scrutiny, and for the Tribunal to ascertain the intentions of the relevant decision makers that represented the corporate body.

Agreed Facts, Transcript and Post-hearing submissions

-

7. The Statement of Agreed Facts (‘SOAF’) is appended as Annex 1. The respondents’ position is that the SOAF is not a full statement of all the facts which HMRC regard as relevant to the issues in this appeal. The Tribunal has made its own findings of fact in addition thereto.

-

8. A transcriber was in attendance throughout the proceedings, and the transcript for each day was made available soon after the day’s hearing.

-

9. The parties made submissions on the law within the allotted time for the scheduled hearing. The submissions on Mr Olsen’s evidence were made sequentially in writing posthearing pursuant to Tribunal’s Directions of 29 March 2021.

-

10. The respondents’ 12-page submissions were lodged on 6 April 2021, together with annotated diagrams to illustrate the acquisition and finance structure in question as directed by the Tribunal. The Appellant’s 14-page submissions were lodged on 16 April 2021, with two appendices: (a) excerpts of transcript the Appellant relied upon, and (b) annotations of those transcript excerpts contained in the respondents’ 12-page submissions. The Appellant also lodged the additional authority of Euromoney.

Legislative Framework

Loan relationship regime

‘441 Loan relationships for unallowable purposes

-

(1) This section applies if in any accounting period a loan relationship of a company has an unallowable purpose.

-

(2) The company may not bring into account for that period for the purposes of this Part so much of any credit in respect of exchange gains from that relationship as on a just and reasonable apportionment is attributable to the unallowable purpose.

-

(3) The company may not bring into account for that period for the purposes of this Part so much of any debit in respect of that relationship as on a just and reasonable apportionment is attributable to the unallowable purpose.

-

(4) An amount which would be brought into account for the purposes of this Part as respects any matter apart from this section is treated for the purposes of section 464(1) (amounts brought into account under this Part excluded from being otherwise brought into account) as if it were so brought into account) as if it were so brought into account.

-

(5) Accordingly, that amount is not to be brought into account for corporation tax purposes as respects that matter either under this Part or otherwise.

-

(6) For the meaning of “has an unallowable purpose” and “the unallowable purpose” in this section, see section 442.’

‘442 Meaning of “unallowable purpose”

-

(a) is party to the relationship, or

-

(b) enters into transactions which are related transactions by reference to it, include a purpose (“the unallowable purpose”) which is not amongst the business or other commercial purposes of the company.

-

(2) If a company is not within the charge to corporation tax in respect of a part of its activities, for the purposes of this section the business and other commercial purposes of the company do not include the purposes of that part.

-

(3) Subsection (4) applies if a tax avoidance purpose is one of the purposes for which a company -

-

(a) is party to a loan relationship at any time, or

-

(b) enters into a transaction which is a related transaction by reference to a loan relationship of the company.

-

(a) the main purpose for which the company is party to the loan relationship or, as the case may be, enters into the related transaction, or

-

(b) one of the main purposes for which it is or does so.

‘1139 “Tax advantage”

-

(a) a relief from tax or increased relief from tax,

-

(b) a repayment of tax or increased repayment of tax,

-

(c) the avoidance or reduction of a charge to tax or an assessment to tax,

-

(d) the avoidance of a possible assessment to tax,

(da) the avoidance or reduction of a charge or assessment to a charge under Part 9A of TIOPA 2010 (controlled foreign companies)

[(e) & ©•••]

-

(a) by receipts accruing in such a way that the recipient does not pay or bear tax on them, or

-

(b) by a deduction in calculating profits or gains.’

Anti-arbitrage rules

-

14. The anti-arbitrage provisions under Part 6 of the Taxation (International and other Provisions) Act 2010 (‘TIOPA’) were introduced in 2005. The arbitrage rules as concerns this appeal were replaced with effect from 1 January 2017 by new anti-avoidance provisions under the heading of ‘Hybrid and other Mismatches’ as Part 6A TIOPA. The superseded Part 6 of TIOPA (in force up to 31 December 2016) would be the relevant enactment during the period of the loan relationship debits under appeal, see Annex 3.

-

15. In broad terms, the anti-arbitrage rules sought to counteract transactions involving hybrid entities, or instruments which would otherwise have given rise to a UK tax advantage, such as when a taxable deduction is not matched by a taxable receipt, or when there is a mismatch between jurisdictions in the characterisation of a related transaction. Neither party has made direct submissions that the anti-arbitrage rules are relevant to the substantive issues under appeal. The anti-arbitrage rules are here noted for reference only, as being an area of legislation featuring in the documentary evidence.

Authorities

The Facts

Background

-

17. The Appellant was a member of a corporate group with its ultimate parent being Joy Global Inc, whose business is in manufacturing mining machinery and equipment. The headquarters for the Joy Global group were in the United States up until April 2017, when the group was acquired by the Japanese company Komatsu Mining.

-

18. In the year 2011, during which the relevant transactions in relation to this appeal took place, the Joy Global group had significant operations in Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, China, South Africa, the US, the UK, and sales offices in numerous other locations.

Corporate entities

-

(1) Joy Global Inc (‘JGI’ or ‘Joy Global’).

-

(2) Joy Technologies Inc (‘JTI’ or ‘Joy Technologies’)

-

(3) JTI Acquisition Company (2011) Limited (‘the Appellant’ or ‘JTIAC’)

-

(4) LeTourneau Technologies Inc (‘LTT’ or ‘LeTourneau’)

-

(5) Joy Global Cayman Finance Limited (‘JGCF’ or ‘JG Cayman Finance’)

Key personnel

-

20. The email exchanges of the key personnel during the crucial period of June 2011 that led to the decision and implementation of the funding scheme resulting in the non-trade loan relationship debits are important contemporaneous records for the purposes of this appeal. The surnames of the dramatis personae are used for ease of reference, and the date and time of an email is noted as an aid to establish the chronological order of the cohort of exchanges, with the time zone difference between the US and the UK being factored in where relevant.

US-based

-

(1) Edward (Ted) Doheny, President and Chief Executive Officer of JGI (‘Doheny’)

-

(2) Mike Olsen, Executive Vice President, Treasurer and Group CFO (‘Olsen’)

-

(3) Patrick O’Brien, Group Vice President of Tax (‘O’Brien’)

-

(4) John David (or Sean) Major, Group General Counsel / Attorney in Fact (‘Major’)

-

(5) Robbin Krueger, Joy US Corporate Legal (‘Krueger’)

-

(6) Kim Kodousek, Joy US Corporate Legal (‘Kodousek’)

-

(7) Paul Wagner, JGI Tax (‘Wagner’)

-

(8) Matt Kulasa, JGI Tax (‘Kulasa’)

-

(9) Erik Eighme, Clifton Davis, etc. of Deloitte US-Milwakee (‘Deloitte-Milwakee’)

UK-based

-

(10) Mike Mannion, CEO of Joy UK at the time (‘Mannion’)

-

(11) Wayne Kisten, CFO of Joy UK at the time (‘Kisten’)

-

(12) Keri Tither, Deloitte UK Tax (‘Tither’)

-

(13) Vicki Willis, then Group Accountant of Joy UK (‘Willis’)

-

(14) Catherine Hodgetts (nee Leith), UK company secretary of Joy Mining Machinery Limited (‘Leith’ or ‘Hodgetts’)

Chronology of key events

to the acquisition of LTT.

Company Inc as seller in connection with the acquisition of LTT.

Deloitte Milwaukee and Deloitte UK on that day to discuss ‘the global tax planning idea’ in relation to the acquisition structure for LTT, attaching a 9-step plan called ‘the Skinny’.

that the acquisition structure ‘will provide Joy UK some fairly substantial prospective tax savings’. A Draft Workplan and a copy of Deloitte presentation were attached.

appointing Olsen, Kisten and Mannion as directors.

the LTT acquisition without regard to the broader benefits.

allotment of shares, the borrowings of $500m (as interest free loan) and $550m (as loan notes), and the assignment of the purchase agreement of LTT.

parent JTI for the loan of $550m.

Assumption Agreement over the rights and obligations of JGI as purchaser of LTT.

‘Project Longhorn’ to acquire LeTourneau

I. Merrill Lynch presentation - 6 April 2011

-

22. A detailed presentation containing 35 slides by Bank of America Merrill Lynch to JGI was entitled Project Longhorn and comprised two parts: (a) Drilling Products Business Case, (b) Longhorn Stock Valuation Discussion, with appendices on: (i) additional valuation detail, and (ii) drilling products and systems buyers.

Drilling Products Business Case

-

23. The summary considerations for the business case covered: (i) macro environment, (ii) sector environment, (iii) Longhorn potential in relation to offshore products and drilling systems, and (iv) the large universe of third-party interest.

-

24. The business case was underpinned by a vast quantity of technical details, with slides containing high density of data, statistics, economics, historical and projected financials, stock price performance of the Longhorn shares. For example, one slide for ‘Positioning for the Next Owner’ in the drilling products business sector shows how to ‘maximise value’ by bringing together four ‘building blocks’ of the business, namely:

-

(a) Largest share of current operating Jackup Designs;

-

(b) Largest installed equipment bases / aftermarket;

-

(c) Newbuild cycle;

-

(d) Turnaround story and operational improvements.

‘Ranch’s competitors more likely to order jackups and equipment when Longhorn is independent;

Demostrate and quantify Longhorn design advantages.’

Longhorn stock valuation discussion

-

26. On valuation of the Longhorn stock, the presentation slides again encapsulate a high volume of information, comprising graphs and histograms to summarise value indicators by key competitors, stock price performance, valuation multiples (e.g. public market multiples/transaction precedents) to arrive at the ‘Illustrative Valuation’ for Longhorn, focusing on drilling products plus mining.

-

27. The focus of the additional valuation detail on Longhorn stock shows the discounted cash flow analysed under the headings of: (i) mining with synergies, (ii) mining without synergies, (iii) offshore products and steel products, (iv) drilling systems, and (v) return on investment.

-

‘A . Seller owns all of the outstanding common stock, par value $.001 pe share (the “Longhorn Stock”) of LeTourneau Technologies Inc, a Texas corporation (“Longhorn”);

-

B. Longhorn is engaged in the business of (i) designing, manufacturing, distributing and selling equipment, and providing aftermarket parts and services, for the oil and gas drilling industry, including jack-up rig kits, complete land rigs, mud pumps, drawworks, top drives, . . (ii) designing, manufacturing, distributing and selling a range of high-performance front-end loaders serving the mining industry worldwide, (iii) designing, manufacturing, distributing and selling new and refurbishing used log stackers for the forestry industry mainly in the United States, (iv) designing, manufacturing, distributing and selling high strength specialty carbon, alloy and tool steel plate products (together with any other businesses of the Longhorn Entities incidental thereto, collectively, the “Business”).

-

C. Seller desires to sell to Buyer the Longhorn Stock, and Buyer desires to purchase from Seller the Longhorn Stock, .’ (underlining original)

-

29. The purchase consideration was stated in the agreement to be $1.1 billion. The purchase price, after working capital price adjustments, was $1.053bn dollars. Other relevant details from the Agreement for present purposes include:

‘the date on which the Closing occurs, which shall be five Business Days following the date on which all conditions set forth in Article 6 shall have been satisfied or waived. ..’

The ‘Global Tax Planning’ Idea

I. Inception of the global tax planning idea - 2 June 2011

Deloitte’s proposal on ‘LeTourneau Acquisition Structure’

-

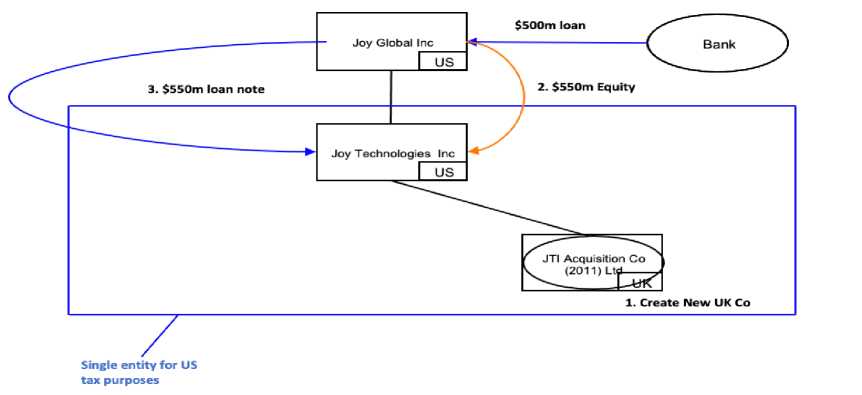

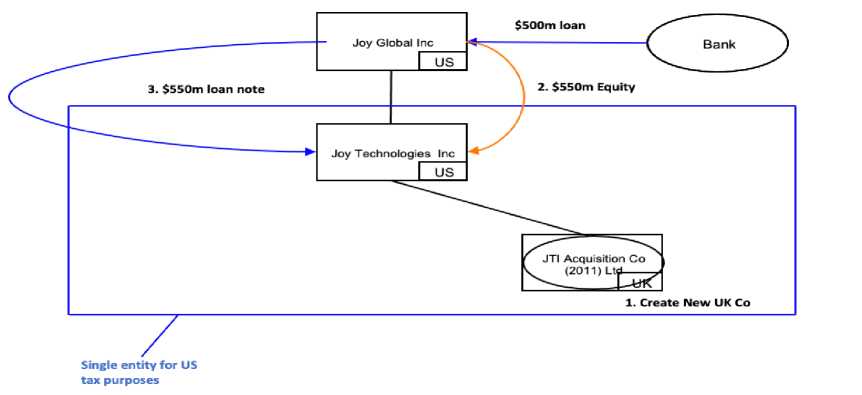

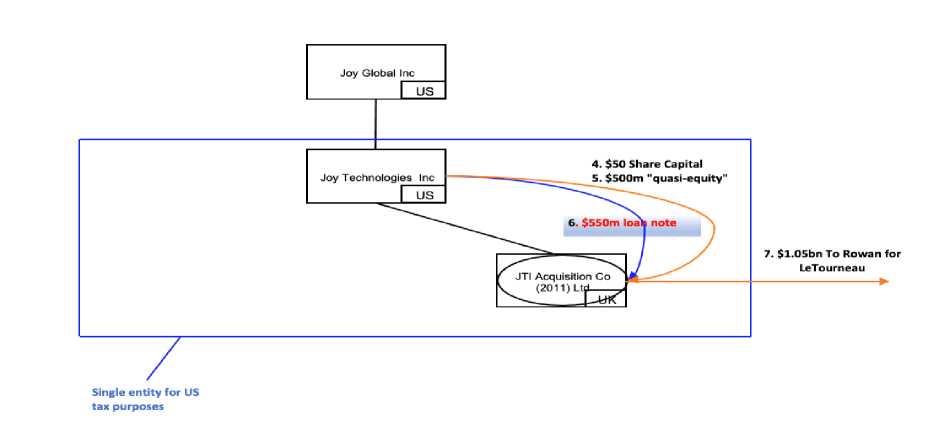

30. Deloitte made a presentation on 2 June 2011 to Joy Global, with the subject heading being ‘LeTourneau Acquisition Structure’ as stated on the first slide, which also contained the caveats of it being at ‘Draft’ stage, and ‘solely for the information and internal use of Joy Global Inc and not to be relied upon by any other person or entity’. The presentation illustrated what came to be known as the ‘9-step plan’ with a sequence of flow chart diagrams. Each step is designated by a heading description on the slide, (italicised below with emboldened abbreviations being used for entities). The flow charts represent an entity in the shape of a rectangle, and use an arrow with annotation to denote the flow and nature of the funds.

-

31. The plan contained 10 steps at this stage, and the first step was concerned with the funding requirement for the acquisition of LTT. The draft plan evolved and came to be known as the 9-step plan in subsequent correspondence between Deloitte and the group, when the first step was no longer being carried in the discussion of the plan. The first step in this draft plan as presented by the slides, is re-labelled below as Step 0 to bring the step numbers in line with how subsequent correspondence made reference to these steps; (underlining below is added).

-

(a) from Bank (with a dotted arrow) to JGI for ‘$500 million note’;

-

(b) JGI (in brackets ‘US’) with ‘$600m’ designated within the entity;

-

(c) JTI (in brackets ‘US’) as an entity below JGI.

-

(2) Step 1: JTI forms a new UK Limited Company (‘UKLtd’), or uses an existing UK entity, which elects to be treated as a disregarded entity for US federal income tax purposes; the flow chart has no arrow, and shows the vertical group structure of 3 entities:

-

(a) JGI (US) at the top;

-

(b) JTI at the middle; and

-

(c) UK Ltd at the bottom; (represented by a rectangle in dotted lines, and with a dotted-lined oval inserted within probably to denote its non-US jurisdiction).

-

(3) Step 2: JGI contributes $550m to JTI; the flow chart is as per step 1, but with an arrow to show the funds flow of ‘$550 million equity’ from JGI to JTI; (UK Ltd as an oval within a rectangle is in solid lines at Step 3).

-

(4) Step 3: JGI loans $550 million to JTI in exchange for an interest bearing note; the flow chart is identical to the one for step 3, except for the annotation of the arrow being changed to ‘$550 million interest bearing note’.

-

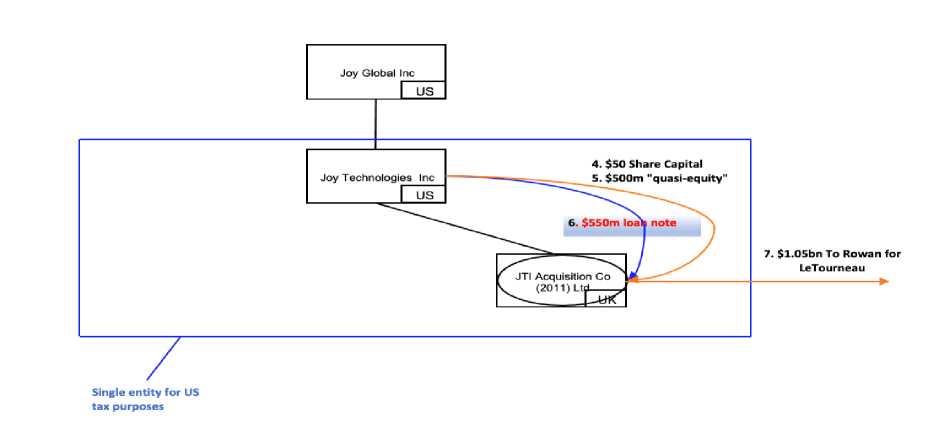

(5) Step 4: JTI contributes $50 million to UK Ltd as equity; the flow chart is the vertical structure of the 3 entities at step 2, with an arrow flowing from JTI to UK Ltd for ‘$50 million equity’.

-

(6) Step 5: JTI transfers $500 million to UK Ltd in exchange for a dollar denominated non-interest bearing note; the flow chart is identical to step 5, except for the description to the arrow from JTI to UK Ltd being ‘$500 million non-interest bearing note’.

-

(7) Step 6: JTI loans $550 million to UK Ltd. The loan should be capable of being listed as a Eurobond (or in the form of multiple original issue discount notes); the flow chart is identical to step 6, except for the description to the arrow from JTI to UK Ltd being ‘$500 million loan’.

-

(8) Step 7: UK Ltd acquires LeTourneau (‘LTT’) for $1.1 billion cash and makes a Section 338(h)(10) election; the 3-entity flow chart in previous steps becomes a 4-entity chart, LTT added below UK Ltd; (LTT is represented as a rectangle in solid lines).

-

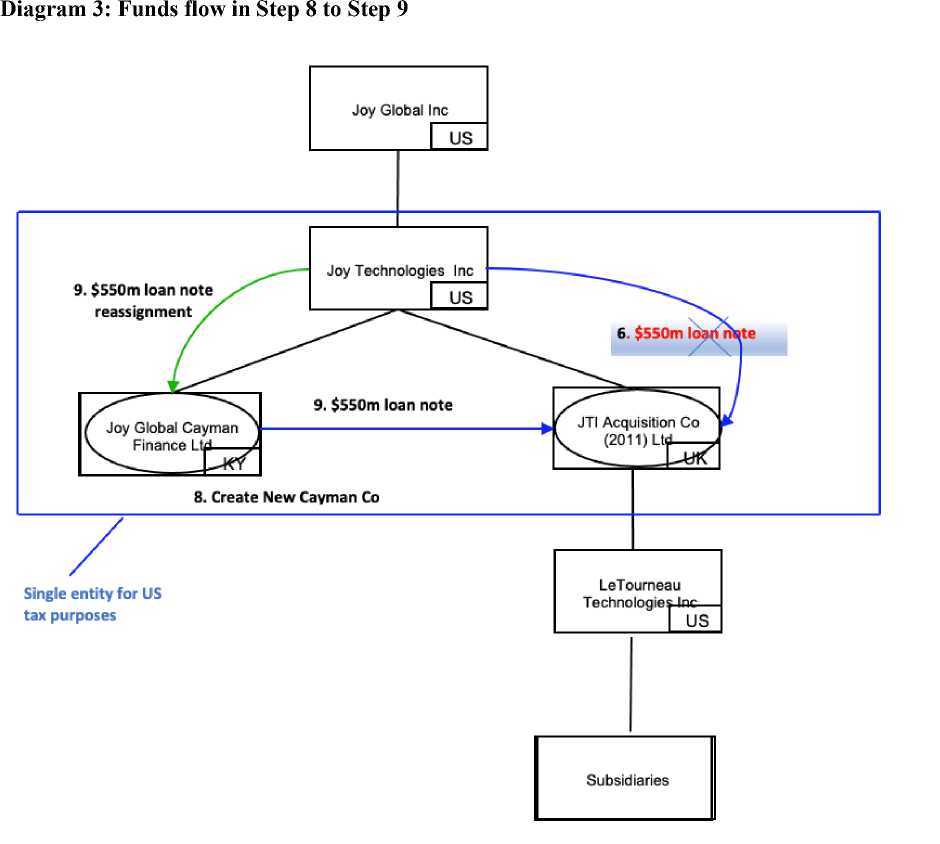

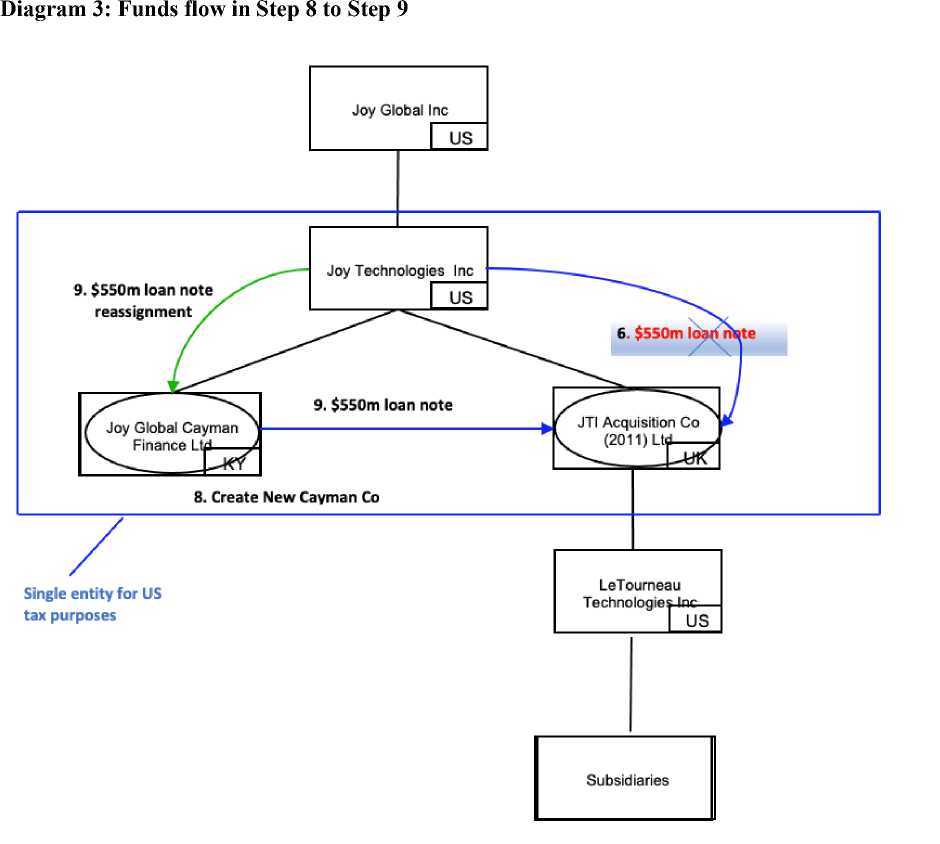

(9) Step 8: JTI_ forms Finance Company (either a US LLC or a Cayman Islands Ltd). If a Cayman Islands Ltd is formed, an election is made to treat it as a disregarded entity for US income tax purposes; the flow chart shows as follows:

-

(a) The vertical line of group structure with JGI on top of JTI;

-

(b) JTI with two branches: right-hand-side 2-entity branch UK Ltd, and LTT vertically below UK Ltd;

-

(c) JTI’s left-hand-side branch in dotted line, Finance Company in a rectangle with an inserted oval in dotted line, sitting at the same level as UK Ltd.

-

(1) UK Ltd’s board of directors hold a meeting to consider the acquisition and funding of the acquisition of LTT.

-

(2) UK Ltd functions as a holding company (i.e. dividend exemption, capital gains exemption, no withholding tax on interest and dividends).

-

(3) Interest income at Finance Company is likely not subject to local income tax.

-

(4) Finance Company and UK Ltd are disregarded entities for US federal income tax purposes; therefore, the loans are disregarded.

-

(5) LTT and its US subsidiaries will be included in JGI’s consolidated US tax group.

-

(6) Facilitates s338(h)(10) election for LTT and relevant US subsidiaries and opportunity to make s338(g) election for foreign subsidiaries.

-

(7) Business and tax considerations:

UK Ant-arbitrage

Deductibility of interest (UK and State)

Timing of deduction

Withholding tax

Currency

Accounting

The 9- step ‘Skinny ’: O’Brien to Olsen/Major - 2 June (5:04pm)

-

33. On 2 June 2011, O’Brien as the Group Vice President of Tax, sent an email to Olsen and Major, with Deloitte-Milwaukee copied in, under the subject heading of ‘LeTourneau Acquisition Structure (Draft Summary for Mike Olsen and Sean Major) - Please review and comment’. The email started by referring to ‘our conference call today with Deloitte Milwaukee and Deloitte UK to discuss in more detail the global tax planning idea they have brought to our attention vis a vis LeTourneau’.

-

34. The ‘global tax planning idea’ was set out in a summary which became the 9-step plan coined as ‘The skinny’ in O’Brien’s email.

‘The skinny is as follows:

-

2. [JGI] will contribute $550 million to JTI.

-

3. JGI will loan $550 million to JTI in exchange for an interest bearing note.

-

4. JTI will contribute $50 million to UK Ltd.

-

5. JTI will transfer $550 million to UK Ltd in exchange for a dollar denominated non-interesting bearing note.

-

6. JTI will lend $550 million to UK Ltd. The loan will be listed as am Eurobond in either the Caymans Islands or the Channel Islands.

Action plan to implement the Skinny

‘Action Steps Required - Next week

-

a. Key is to have UK Ltd created as quickly as possible.

-

b. Deloitte would guide Eversheds (or other UK law firm as directed by Sean Major) on the preparation of all documents necessary for the creation of UK Ltd.

-

3. Work with Ken Stark in drafting the necessary loan agreements to effect the steps outlined above.

-

4. Coordinate with Corporate Legal on the preparation of the necessary US documentation for the equity transactions between JGI and JTI and JTI and UK Ltd and Cayman.’

-

36. O’Brien’s email attached a copy of ‘the slides that were used in today’s discussion with Deloitte’ (supra), and ended by noting that ‘Erik Eighme [of Deloitte] will be sending over their fee proposal for this project later today or early tomorrow.’

-

37. O’Brien’s email was forwarded directly by Major at 5:11pm on the same day to Kim Kodousek of Joy Global US (Corporate Legal), marked as ‘High’ importance, with a one-line message: ‘Pls take a look and tee up Eversheds [UK law firm] for what could be a fire drill’.

Deloitte’s fee proposal: O’Brien to Olsen - 3 June (6:13pm)

-

38. On 3 June 2011, O’Brien emailed Olsen regarding ‘Deloitte Fee Quote - LeTourneau Acquisition Structure’. In this email, O’Brien mentioned the two options in the fee proposal ‘for supporting the interest deduction’.

-

(1) Option 1 was to obtain an Advance Thin Capitalisation Agreement (‘ATCA’) at a total fee in the range of $280K to $340K.

-

(2) Option 2 was ‘less costly’ by $10 to $15K by asking Deloitte to prepare ‘a debt defense report’ (American spelling stands as in original).

‘Attached is Deloitte’s fee quote in USD translated at today’s spot (GBP to USD):

Design, Implementation and Technical Analysis - $240 to $290K

Assistance in obtaining an [ATCA] - $40 to $50K.

Total quote $280 - $290K.’

‘If we wanted to shave $10 to $15K from the above, Deloitte could prepare a debt defense report that we could use if HMRC later challenged the appropriateness of the interest deduction claimed in the UK that this structure creates. In my professional opinion this would not be the way to go.

At this juncture Deloitte has indicated that obtaining the ATCA would be fairly straightforward.

[Option 1] This would give us assurance that the future deductions would be honored and would eliminate any current or future FIN 48 issues being raised by E&Y.

[Option 2] The less costly approach would not provide the same level of comfort from a HMRC audit risk perspective. E&Y may also raise the FIN48 Issue since they may be reluctant to accept Deloitte’s debt defense report being MLTN’. (sub-paragraphing and italics added)

-

41. There were earlier exchanges of email between O’Brien and Olsen regarding Deloitte’s fee quotation. Olsen asked O’Brien for his recommendation regarding the two options. Olsen found O’Brien’s initial response ‘confusing’, and O’Brien’s 6:13pm email sought to clarify his opinion. In his initial response to Olsen, O’Brien set out the estimated UK tax implications:

‘The first full year anticipated income tax savings in the UK would be approximately 13 times their fee quote (conservatively computed as follows: $500 million *4% *23%). In addition we would have net state income tax savings inuring to JTI conservatively estimated to be somewhere in the range of $300 to $500K per year.’

II. Implementation of the idea: from ‘Skinny’ to Workplan

Informing Joy UK of UK newco: O’Brien to Kisten (of Joy UK) - 6 June (9:50am)

‘With the acquisition of LeTourneau we have identified an acquisition structure that will provide Joy UK with some fairly substantial prospective tax savings.’

‘The new UK entity (Eversheds will be providing us with its formal name later today or tomorrow) .. and will include [Kisten], Mike Mannion and Mike Olsen as directors. Eversheds is working up the documents to form the UK entity and may contact you . for information needed to make you and Mike Mannion directors.’

-

44. There were two attachments accompanying the email, one being Deloitte’s presentation slides, and the other was referred to as ‘the draft work plan for the steps necessary to have the acquisition structure in place prior to closing date for the LeTourneau acquisition which should occur later this month’.

UK company secretary advised of UK Newco: Krueger to Leith - 6 June (4:49pm)

‘Just a heads up, in case you didn’t already hear. We are forming a new UK company (probably tomorrow) to handle our acquisition of LeTourneau. See the attached step plan from Deloitte.

. Eversheds is doing the heavy lifting on the formation. I have let them know you should be nominated as company secretary.’

-

46. On 7 June (7:15am), Leith replied, stating that ‘this was news to me’, and gave a 10-point summary of what she knew after having spoken to Eversheds, some of which are:

-

‘1 . Eversheds to perform the incorporation service - same day electronic incorporation with Companies House;

-

2. Eversheds to draft first resolution (forming company, appointing dirs., and sec, and allotting shares to JTI) and complete the appropriate registers;

-

3. Initial share allotment - perhaps 1 ordinary share $1,000? Fully or partly paid? We can then fill it up when the loans are in place? Whatever the business decide; ...’

Draft Workplan for status update: O’Brien to Eversheds & Deloitte team - 7 June (15:43)

-

47. O’Brien emailed various individuals from JGI, Deloitte (UK and US), and Eversheds with the Draft Workplan entitled ‘Joy Global Inc. LeTourneau Acquisition Structuring’. It is a 3-page Excel document to monitor the progress of the first 7 steps set out in the 9-step Skinny. The 5 column headings are: (i) Action/Document, (ii) Target/completion date, (iii) Responsible Party, (iv) Status, (v) Description/Comments.

-

48. From the Target/completion date column, the window of operation to complete the 7 steps spanned the 10-day period from 6 June 2011 to 15 June 2011.

-

49. Tax personnel was named as the sole or one of the responsible parties in Steps 1,3, 5 and 6, being the four steps related to ‘UK Newco’ formation and funding in the 7-Step Workplan.

‘Deloitte UK will coordinate with JGI Tax and Eversheds to prepare package of information on the investment opportunity being considered by [JTIAC]. Board agenda and proposed

minutes being progressed by Eversheds. Draft of Note for Step 6 needs to be included in this package. ’ (underlining original)

‘Corporate Treasury, working with Corporate Tax, will draft loan agreement. Deloitte UK will provide a sample note with preferred terms from a UK perspective.’

-

(3) Step 5: JTI contributes $500M to UK Newco as Equity in the form of USD denominated non-interest bearing note - entry (b) and (d) in relation to drafting and finalising the loan agreement: Joy Global Treasury/Tax.

-

(4) Step 6: JTI loans $550M to UK Newco in the form of a USD denominated Eurobond: Eversheds/ JGI Treasury & Tax for the step heading, with comment to the step heading being:

‘Eversheds will take the lead in drafting this note using terms similar to those provided by Deloitte UK for Step 5. Terms should be such that the note can be listed as a Eurobond. Note will be denominated in USD. Final interest rate to be determined. Loan must be registered as a Eurobond by the time of the first interest payment.’ (italics added)

‘Corporate Treasury, working with Corporate Tax, will draft loan agreement.

Deloitte UK has provided a sample note as guidance.’

UK elements update: Tither to O’Brien/Olsen etc & Deloitte US - 7 June (UK 12:09pm)

‘The documentation ... (being presentation given to the Board of Directors, prepared by Merrill Lynch, to support the business case for the transaction, and the LeTourneau company presentation) should be included in the board pack to help the directors of [JTIAC] to make a fully informed decision to proceed with the acquisition. ..’

-

(2) Step 1d involved the circulation of the board pack, and Tither referred to further discussion with an Andy Wilde to determine whether ‘to include additional information over and above the documentation received to date’.

-

(3) Step 1d involved the convening of an actual board meeting to approve the acquisition of LTT by JTIAC. Tither advised that ‘it would be beneficial if there could be someone available at the meeting (i.e. via telephone) who could answer any questions the Board members may raise’.

-

(4) Step 5: JTI contributes $500M to UK Newco as Equity in the form of a USD denominated non-interest bearing note, Tither advised that ‘a sample note’ would be circulated to the group by ‘tomorrow morning UK time’.

-

(5) Step 6: JTI loans $550M to UK Newco in the form of a USD denominated Eurobond, Tither attached ‘a sample note in a format suitable for listing on an exchange subsequent to the transaction’, and advised that the listing particulars could be circulated in due course if required.

-

51. In relation to Tither’s point about ‘someone who is key to the internal Joy discussions regarding the acquisition’ be available for the board meeting, Krueger (JGI Tax) replied (7 June, 1:08pm) to Tither as follows:

‘Are you aware that all of the board members of [JTIAC] are employees of ours? They are well informed on our intentions and, as a matter of fact, one is Joy Global’s CFO [i.e. Olsen] and a contributing architect of this plan. He is one of the two “senior management” that is updated by Pat [i.e. O’Brien] on a nightly basis.’

‘I’m not really in favour of presenting more paperwork to them, especially in such a formal manner. ..

I would like to dispense with the formality of providing a board packet.’

The jot-down list of concerns: Willis to Kisten/O’Brien/Wagner/Tither - 8 June

‘1) Worldwide debt cap (we are currently trying to reduce net debt in all UK companies)

-

2) CFC

-

3) Thin Capitalisation - I understand that loans must be of an amount that a third party would be prepared to lend and at interest rates that they would be prepared to give us.

-

4) This appears to be being done solely for tax planning and therefore may impact our low risk rating. We have stressed to CRM2 in the past we do not go into this type of transaction.

-

5) We will need to explain to our CRM why we have this new company as it will be part of our UK tax group.

-

6) If I understand correctly the balance sheet will be:

Investments 1,100M

Loans 1,050M

Share Capital 50M

The interest will be charged on the loan which will make the reserves negative - then there will be a dividend block. Am I missing something?’

-

54. Kisten replied, and asked Willis to raise the issues with O’Brien and Wagner, to whom Willis forwarded the list, with Leith, Kisten, Tither copied in. Wagner responded as follows:

‘A lot of these questions are driven by the UK’s concern in changing profile to a more aggressive structure. We went through something similar in a recent Australian transaction where Deloitte’s Australian team had to do some hand holding on these types of questions/issues... ’

Tax Planning Matrix not to go into Board Pack: Wagner to Leith/Deloitte - 10 June (3:16pm) 55. In accordance with Step 1(d) in O’Brien’s Workplan (§49(1)), Leith was putting together the ‘Board Pack’, which contained the documents and information prepared by Deloitte UK, JGI Tax, and Eversheds for the first board meeting of JTIAC. On 10 June (3:06pm) Leith emailed the Board of Directors of JTIAC with two zipped attachments. The body of text set out the contents of the Board Pack, to cover two areas regarding: (a) Incorporation Resolutions, and (b) Allotment, Financing, and LeTourneau Acquisition Resolutions.

-

56. Under the heading of ‘Documents in support of the resolutions’, the Board Pack as collated by Leith included: (i) Bank of America Merrill Lynch Presentation, (ii) JGI Management Information presentation, and (iii) O’Brien ‘Tax Planning Matrix’ (of 7 June).

-

57. While Leith’s email was to the three directors only (i.e. Olsen, Mannion, and Kisten), Wagner (JGI Tax) became privy to Leith’s email, and responded, with a host of others being copied in from Deloitte-UK Manchester, as well as O’Brien and Krueger. The email was marked for ‘High’ importance, and was addressed to ‘Catherine and Deloitte Team’.

‘I do not think we should include the “Tax Planning Matrix” from Pat O’Brien should be included [sic] in this correspondence. Assuming Deloitte agrees I will ask that you please re-send this email without that attachment.’

Tax Planning Matrix re-surfaced to check the ‘math’: Hodgetts to Kulasa - 13 Nov 2012

‘Matt, attached is the tax planning document that was circulated at the time of the incorporation of JTIA - I calculate that the saving of having it in the UK is actually $3.8m rather than the $6.8m on the document. I just wanted to check with you as I have put $3.8m per annum in the justification.’

-

59. Below her email to Kulasa, Hodgetts attached O’Brien’s email of 7 June 2011, which was circulated to Hodgetts, Kisten, Willis, Mannion, Kulasa, (plus two others), and Olsen, Major, Kodousek, and Wagner, under the following subject heading, and the cover email to the attached matrix referred to ‘the math’ behind the tax planning.

‘Tax Planning Matrix - LeTourneau Acquisition - Estimated Tax Savings Using 5% interest rate

As a follow up to today’s call, attached is the summary of the [sic] tax planning and “the math” supporting estimated annual global tax savings which would inure to the benefit of our organization as long as the debt structure remains in place. Of course the actual tax savings will hinge on the interest rate that is used for the intercompany transactions. For now we are estimating the interest rate to be 5%.’

[JGI] will acquire [LTT] and its subsidiary group for approx. $1.1billion.

[LTT] and subsidiary group primary manufacturing facilities are in the USA.

[LTT] and subsidiary group sell product throughout the world.

[LTT] and subsidiary group sell product throughout the world.

[LTT] and subsidiary group manufacture OEM and parts for two key segments, mining and oil drilling.

The funding of [LTT] will be a combination of US cash and US bank borrowings.

Tax Planning Structure

[The 9-Step Plan as presented in the ‘Skinny’ email]

At the end of the day the structure is as follows

JGI’s investment in JTI will have increased by $550 million

JGI has a loan receivable from JTI in the amount of $550 million

JTI has a $550 million investment in UK Limited

JTI has a $550 million investment in Cayman Islands Finance Company

UK Limited [JTIAC] will have a loan payable to Cayman Islands Finance Company.’

‘Assume interest rate on all debit within the structure is 0.05 [i.e. 5%]

Assume UK tax rate is 23% on a prospective basis

Assume US federal income tax rate is 35%

Assume JTI US state income tax rate is 2% and

JGI US state income tax rate is 0%

Functional currency throughout global structure is USD

The ‘math’ as projected by O’Brien on 7 June 2011

-

63. The UK Newco was given the name JTI Acquisition Company (2011) Limited and was incorporated on 8 June 2011. Its principal activity was described as intermediate parent undertaking, and the directors appointed were Olsen, Mannion, and Kisten.3

-

64. JTIAC had no employees other than the directors, no physical business in the UK, no cash or assets until given to it at the appointed time according to the Deloitte Step plan. In Leith’s email of 10 June 2011 to Olsen, Mannion, and Kisten regarding the Board Pack, she set out the contents of the ‘Incorporation Resolutions’ to include:

‘Draft Minutes attached. Including Banking Resolution (JGI Standard Banking Resolution giving JGI officers permission to create and arrange bank accounts for JTI Acquisition Co (2011) Ltd. Previous consent given.’

Draft Board Meeting Minutes: Krueger to Leith/Eversheds - 15 June (4:34pm)

-

65. Krueger (JGI Legal) emailed Eversheds in respect of the contents in the draft minutes for the upcoming UK board meeting, and referred to his attempt to ‘blackline the changes’ and a new draft attached for review. Krueger informed Eversheds that the letter referred to at Section 1.3 of the minutes would be signed by Doheny and distributed to the board the next day. The draft minutes were to be adopted as the minutes of the board meeting to be held by the directors of JTIAC to pass the resolution to acquire LeTourneau.

-

66. The letter mentioned at Section 1.3 of the Minutes was signed by Doheny as President and Chief Operating Officer and dated 16 June 2011, (the ‘Memo’ as it was also sent to the directors as a memorandum). The Memo was addressed to Olsen, Mannion and Kisten as directors of JTIAC. It reads as follows:

‘As you are aware, [JTIAC] has been presented with the opportunity to acquire the shares of [LeTourneau]. As you contemplate this opportunity, and the benefits this acquisition could provide to [JTIAC], it is important that you consider this transaction on its own merits only and not give consideration to any broader benefits that may be derived by the group of the companies owned by Joy Technologies Inc.’

Minutes of the Board Meeting held in US-Milwaukee 20 June 2011 at 6:30am

-

67. Olsen (in the chair) and Mannion and Kisten present, with Leith, Major, Krueger, O’Brien, Kodousek in attendance. Section 1.3 of the Minutes states: ‘The Directors confirmed that in advance of the meeting they had each received a letter from the Company’s shareholder, [JTI], wherein they were asked to consider the Acquisition [of LTT] on its own merits, and without consideration of any broader benefit to the group of companies owned by [JTI]’.

-

68. Section 2.1 of the Minutes states ‘the purpose of the meeting was to consider and, if thought appropriate, for the Company to approve’:

-

(a) the allotment of 49,999 shares;

-

(b) the borrowing of US$500m from JTI under a loan agreement;

-

(c) the borrowing of US$550 from JTI by issuing loan notes;

-

(d) the assignment of the Stock Purchase Agreement,

-

(e) the acquisition of LeTourneau.

-

VI. Financing of JTIAC to complete LTTpurchase - 21 &22 June 2011

Share capital allotment - $50m: Step 4 of Skinny

-

69. In June, an application was made for the allotment to JTI of 49,999 Ordinary Shares in JTIAC of US$1000 in the value of $50m. This application was subsequently approved in the Board Minutes of JTIAC dated 20 June 2011.

Quasi-equity (interest free loan) - $500m: Step 5 of Skinny

-

70. On 21 June 2011, a non-interest bearing loan agreement (Note Number 923) between JTI and JTIAC in the sum of $500m was executed, which was informally referred to as ‘quasiequity’ as no interest was payable on this loan. Sean D Major as ‘Secretary’ signed the ‘Lender’ (JTI) and John D Major as ‘Attorney in Fact’ signed for the ‘Borrower’ (the Appellant).

Intercompany debt - $550m interest bearing loan notes: Step 6 of Skinny

-

71. By deed executed on 21 June 2011 by John D Major as Attorney in Fact, witnessed by Kim Kodousek, consequent upon the resolution of its board of directors passed on 20 June 2011, JTIAC authorised $550m Loan Notes to be constituted by the deed (internal reference ‘Loan Note Instrument 921’). The relevant clauses for the purposes of this appeal are:

beginning October 15, 2011 ... ’ (clause 1.1 amongst others definitions).

-

(2) Interest - ‘The Company shall pay to the Noteholders interest on the outstanding Notes calculated using the One Year LIBOR rate plus 3.5% per annum. Interest will be paid in arrears on each Interest Payment Date’ (clause 4.1).

-

(3) Redemption - ‘On June 21, 2021, the Company shall redeem all the Notes at par together with all interest accrued to the date of redemption ...’ (clause 5.4).

-

(4) Transfer - ‘Every instrument of transfer must be signed by or on behalf of the transferor and the transferor shall remain the owner of the Notes to be transferred until the name of the transferee is entered in the Register in respect thereof’ (clause 8.3).

Assignment of JGI’s Stock Purchase Agreement to JTIAC to acquire LTT

-

72. On 22 June 2011, JGI’s Stock Purchase Agreement dated 13 May 2011 with Rowan Companies Inc to acquire LeTourneau was assigned to the JTIAC, and was completed on the same day. Article 11.5 of the JGI Stock Purchase Agreement provides, inter alia, that:

‘. (without the consent of Seller) Buyer may assign this Agreement in whole or in part to any of its Affiliates (including, without limitation, Buyer’s right to acquire the Longhorn Stock); provided further that no such assignment shall release the assignor from any of its obligations hereunder.’

-

73. The ‘Assignment and Assumption Agreement’ entered into by Joy Global (Assignor) and JTIAC (Assignee) on 22 June 2011 is a two-page document of 9 clauses, signed by: (a) Sean D Major in his capacity as ‘Executive Vice President/ General Counsel and Secretary’ of Joy Global Inc. and (b) John D Major in his capacity as ‘Attorney in Fact’ on behalf of JTIAC.

-

74. Olsen confirmed in evidence that John D Major was given power of attorney by the directors of the Appellant to execute all the documents necessary for the Deloitte scheme. When asked whether Sean D Major and John D Major is the same person but signing in different capacities, Olsen think it was ‘the same guy’ but ‘not sure why there are two different signatures ... why it was John D versus Sean’4 (see also §70).

Flow of funds to complete LTT acquisition

-

75. The first bank statement for JTIAC’s account with JP Morgan Chase Bank was for the period 15 to 30 June 2011, and captured the transactions to bring the Appellant into funds to complete the LTT purchase. The bank statement shows JTIAC’s address at 100E Wisconsin Avenue, Suite 2780, Milwaukee in US, which is the registered address of Joy Technologies Inc. Three sums were deposited as ‘Book Transfer Credit’ on 21 June 2011 (the eve of the completion date) with the following description:

-

(1) From JTI ref: Loan 922 re LeTourneau Technologies Inc acquisition $550,000,000.

-

(2) From JTI ref: Loan 923 re LeTourneau Technologies Inc acquisition $500,000,000.

-

(3) From JTI ref: Equity contribution [reference] $50,000,000.

-

76. On 22 June 2011, the withdrawal took place to complete the purchase of LTT in the sum of $1,045,653,609.41, leaving a closing balance of $54,346,390.59.

-

77. By letter dated 8 August 2011, John David Major5 as Director of the newly formed company Joy Global Cayman Finance Limited (‘JGCF’) in Cayman Islands wrote to JTIAC at its UK address in Worcester, and enclosed a transfer deed executed in relation to the assignment of the $550m interest bearing loan note receivable by JTI in favour of JGCF.

‘We write further to the deed (“Deed”) dated June 21, 2011 constituting the Loan Notes. . pursuant to clause 8 of the Deed, Joy Technologies Inc. .. has transferred US$550,000,000 Loan Notes (being its entire holding of Loan Notes) and its rights to interest accrued thereon (US$3,100,350 at the date of transfer) to Joy Global Cayman Finance Limited.’

Post-acquisition responses/ reporting/ governance issues

-

79. On 6 July 2011, Global Commercial Credit LLC as the insurer of accounts receivables for several scrap metal suppliers to LTT wrote to Olsen to enquire about the new legal structure of LTT following its change of ownership. Olsen forwarded the enquiry to O’Brien, who replied to the insurer on ‘the legal entity organisation structure post acquisition’ as follows:

‘1. [JTI] is a wholly owned subsidiary of [JGI]. Joy Global Inc is the publicly traded entity (JOYG) which operates as a holding company.

-

2. The UK entity, [JTIA] is a disregarded entity for US federal income tax purposes.

-

3. The Cayman Islands entity holds a note receivable from the UK entity, this structure is set up from a tax planning perspective and there are no employees or tangible assets in either entity other than the intercompany notes receivable/payable.

-

4. The legal organisation structure of [LTT] did not change with our acquisition.’ (emphasis added)

-

80. On 22 August 2011, Deloitte made a presentation to JGI on ‘Global Tax Vision’, which set out a global tax strategy focused on the Effective Tax Rate (‘ETR’). The LeTourneau acquisition structure was included as an example.

-

81. Olsen’s 3rd Quarter 2011 presentation to the main Board of Directors of Joy Global Inc on ‘Global Tax Strategy’ of the group adopted some of the key slides in the Deloitte’s Global Tax Vision presentation. The contents of these slides (headings in italics) included:

-

(1) On Keys to Effective Tax Rate to deliver a Global Tax Strategy, the focus is on some ‘simple principles’, such as: (i) align income with low taxed jurisdictions, (ii) minimise non-US income tax, (iii) repatriate high taxed earnings, and so on. Two primary areas of strategic focus are identified as generally the driver for multinational’s ETR, namely: (i) financing, and (ii) business Model optimisation.

-

(2) On ETR Drivers and Key Considerations, a comparison of the tax rates in other jurisdictions of the group entities against the US tax rates is set out, followed by an entry to highlight the UK jurisdiction with the acquisition of LTT as an example:

Tax

Treasury Management

Operating Model

-

(4) Vision for the Future - ‘minimise Non-US tax (Australia and UK Financing)’ being the first item of the vision.

-

(5) Key Benefits and Considerations - JTIAC’s acquisition of LTT is the first main reporting item, in terms as follows:

-

- Interest expense at [JTIAC] is likely deductible for UK tax purposes and available to offset income of Joy Global’s UK group (via group relief). Initial annual benefit of approximately $6.2M ($550M*4.5% (estimated interest rate) * 25% (tax rate)). ..

-

- Interest expense at [JTI] is likely deductible for state tax purposes.’

III. Directors' concerns about corporate governance - March 2012

-

82. In mid-March 2012, Kisten and Mannion expressed concerns as the UK directors of the Appellant in relation to corporate governance and the absence of any LTT performance information. In an email to O’Brien, Mannion and Hodgetts copied in, Kisten stated: ‘For the sake of good governance we need to undertake board meetings and preserve the tax benefits.’

Advance Thin Capitalisation Agreement - 2 November 2011

-

83. On 2 November 2011, on behalf of the Appellant, Deloitte UK applied to HMRC for an Advance Thin Capitalisation Agreement (‘ATCA’). The financing for the acquisition of the LTT shares by the Appellant in the sum of $1,100m was detailed in a table:

|

Sources | |

|

Equity share capital |

$50m |

|

Quasi-equity |

$500m |

|

Loan from JTI (USD LOBOR + 3.5% interest) |

$550m |

|

Total |

$1,100m |

-

84. The clearance sought by the application was stated in the following terms:

‘.. [to] provide confirmation that the loan notes issued by JTI AcqCo to JTI in the amount of $550m, and subsequently contributed by JTI to JGCFL, can be considered to be at arm’s length for the purposes of the UK transfer pricing legislation contained at Part 4, TIOPA 2010 and that the interest arising on this debt will be deductible for tax purposes in the following accounting periods, provided the following covenants are met:

|

Year ended 31 October |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

|

Interest Cover (EBITDA: Net Interest) |

2.5x |

3.0x |

3.5x |

4.0x |

4.0x |

|

Leverage (Net Debt: Equity) |

1.5x |

1.25x |

1.0x |

1.0x |

1.0x |

Interest /Dividends in relevant accounting periods

-

86. In the accounting period ending 31 October 2011, no interest was paid by the Appellant, contrary to the terms of the deed executed for the loan notes of 21 June 2011. In an email dated 25 April 2012 in response to the discussions between Willis and Ernest Young, UK (‘EY UK’) as Joy UK’s accountants on the deductibility of interest for JTIAC, O’Brien wrote under the subject heading of: ‘Group interest payments - 12 month rule’, and gave direction not to include any interest for the period ending 31 October 2011.

‘Please bear in mind that we do not want any deductible interest for the UK FY 11 filing as this would cause the UK tax rate to be less than that which was used for the purposes of determining the US FY 11 foreign tax credit. This was communicated to E&Y US and E&Y UK tax groups during FY11 close.’

-

87. Interest was paid from 2012 onwards, and the interest paid in 2013, 2014, 2015, and 2016 was financed by reductions in debtor balances and the issue of further loan notes to the Cayman Islands Finance Company. These interest payments represent the non-trading loan relationship debits over the four accounting periods, which were then surrendered to other Joy UK companies as group relief.

-

88. Up to and including 28 October 2016, no dividends have been paid up from LTT.

Enquiry to closure notices

-

89. By letter dated 28 September 2018, HMRC Officer Gallacher asked RPC and Deloitte to highlight and identify contemporaneous evidence that JTIAC’s acquisition of LTT, and the associated finance, were driven by commercial reasons. Ten specific questions were set out for response. By letter dated 31 October 2018, the responses from RPC were general and unsupported by any contemporaneous evidence within the 17,000 documents provided.

-

90. Excerpts of RPC’s reply of 31 October 2018 to some of the questions are as follows.

-

(1) The financial statements for accounting period ending 31 October 2011 show that the principal entities acquired by JTI were based in the US, Canada, Brazil, Australia and China. As there are no obvious links, can you please explain why the UK was chosen as the location for a holding company? (Qt 2)

‘The following comments are without prejudice to our primary position ... that JGI’s decision to incorporate a holding company at UK level is not relevant to determining the statutory question at hand. ..’

‘. Debt was expected to serviced by paying dividends up to the UK company. . There would also be earnings from the acquired group . Post-acquisition, however, [LTT] produced less cash than had been originally forecast .’

‘We would again emphasise our view that any decision made at group level to incorporate a holding company in the UK is irrelevant to the question of whether JTI [sic should be JTIAC] had an unallowable purpose. .’

‘. Mr Doheny was asking board directors not to consider any broader benefits and to consider the transaction on its own merits, so the motive for raising this question is not understood.’

‘There were periodic (quarterly) board of director meetings where updates on the [LTT] acquisition/performance were provided and discussed. .’

‘There was no dividend block. .Excess cash of JTI was swept to JGI . in the normal course of cash management, with JTI carrying a note receivable. No value was stripped out of the entity that would hinder any ability it otherwise would have had to service this debt. There were accordingly no reasons to pay any dividends up.’

‘In January 2017, the loan was assigned to a Barbadian-based entity (Joy Global China Holding SRL). The loan was repaid by December 2017. There was no tax benefit generated as the UK entity was not generating taxable income (interest payments would otherwise have been deducted).’

-

91. On 13 November 2018, Officer Gallacher gave his view of the matter in a 13-page letter, having sieved through circa 17,000 documents provided by RPC with ‘minimum levels of itemisation’, Officer Gallacher gave his view that:

‘HMRC can find no evidence that what the directors were seeking to achieve as a result of the expenditure included a main business or commercial purpose.’

-

92. Officer Gallacher’s view of matter concluded by stating that HMRC ‘are conscious that we may not have had the chance to analyse everything’ within the 17,000 documents, and invited the Appellant to respond by 18 January 2019 with any key information or documents that support the view that the transaction as structured was commercial.

-

93. On 13 May 2019, Officer Gallacher issued closure notices for the four accounting periods ending 31 October 2012 to 2016. The conclusion given in each of the four notices is the same:

‘HMRC considers that the amounts of Non-Trade Loan Relationship (NTLR) debits included by [JTIAC] in its company tax returns in respect of the loan relationship which existed between [JTIAC] and Joy Global Cayman Finance Ltd in each of the periods, including this one, fall to be disallowed in full. As such, these NTLR debits cannot be brought into account in [JTIAC] for corporation tax purposes under S441 CTA 2009.’

Olsen’s witness evidence

-

94. The material aspects of Mr Olsen’s evidence with which I have reservations are illustrated by some of his replies during cross-examination. Olsen’s evidence was completed on Day 1 of the hearing with the Tribunal sitting later to accommodate the time zone difference with Mr Olsen attending from the USA. For ease of reference, his replies and citations of documentary evidence are italicised. All references to the transcript are from Day 1, and the page references within the Day 1 transcript are given in brackets.

On the proposal being a ‘group policy’ and ‘intercompany transaction’

-

95. When asked about his knowledge of the Deloitte acquisition structure as producing a tax benefit for the group, Olsen accepted that: ‘It was an added benefit of the acquisition’ (169).

-

96. In relation to Olsen acting in his capacity as a director of the Appellant, several questions were put to him.

-

(1) That the directors of JTIAC had no remit to negotiate some other acquisition structure, the reply was: It was a yes or no. (164-165)

-

(2) When asked about the final decision taken at the Board Meeting, and the Memo to assign the Stock Purchase Agreement, and ‘being realistic’ about his ‘fiduciary duties’:

Q: ... on the precise terms it was offered which is with the particular borrowing and on the understanding that you would then surrender the tax debits and various elections would be made, you were conscious of the fact that by taking the assignment, a benefit would be conferred to the other members of the UK group?

A: Based on the Deloitte material, yes. (172)

Q: .. .that ‘Joy Global does it all the time to consider the wider group benefit as a factor in taking a decision’; that ‘you can’t ignore the fact that the [Appellant] company is a member of the group?’

A: Right, once again I will go back to the point made earlier: Joy Global would not allow tax to drive the strategic decision-making but at the same time, Joy Global will do everything in its power to exercise transactions in the most tax efficient process.

Q: As a director of the Appellant, you knew and understood that as a group policy?

A: It’s not only a group policy, but it would be a policy for all of the Joy Global entities around the world, and once JTI Acquisition came into play, it was also their driver, to be as tax efficient as possible.

Q: And that included the benefit of the other members of the UK group?

A: That’s correct.

Board meeting decisions as the culmination of a process of thinking and consideration

-

97. When asked that by 20 June when the Board of Directors met to pass the resolutions, and that ‘it was right that the other two [UK] directors relied on you’ because ‘you had done a lot of thinking and considering and analysis’ and spoken to O’Brien about the Deloitte acquisition structure, and that ‘you knew all of that’ before 20 June, Olsen replied: ‘I did’(169).

-

98. Olsen’s knowledge of the Deloitte plan was tested further with the following questions.

-

(1) That Catherine Leith had included the Tax Planning Matrix as one of the documents ‘relevant’ to the decisions to be taken at the Board Meeting of 20 June 2011, Olsen did not deny it: ‘Yes, it is difficult for me to express an opinion on what Catherine thought, but certainly her email seems to have included it.’ (171)

-

(2) When asked that ‘it didn’t matter whether the tax matrix was included or not because you had read it and seen it and understood it’: ‘That’s correct.’ (171)

-

(3) In relation to Paul Wagner’s email not to include the Tax Planning Matrix -

Q: .. that the board packs were put together for presentational issues. So they didn’t want the board resolution, the minutes, to record that you had had the tax matrix in front of you. That is what this email suggests? (171)

A: ... Paul was a middle tax manager and I am not sure what his thought process was, but certainly the Deloitte proposal was known by Wayne [Kisten] . being the CFO, he certainly would have been aware of the Deloitte material. (172)

On whether 7 steps or 9 steps in the plan

A: I guess I wouldn’t characterise myself as being happy to stop at step 7, .

our objective was relative to where the debt was, you literally could stop at point 7 . I was looking at it from the perspective of placing debt outside the US. .

A: No, I don’t think that the nine-step plan was ever discussed as the alternative of stopping at step 7. .

Replies on being cross-examined on email exchanges

-

(1) In relation to Krueger’s email of 6 June 2011 to give Leith ‘a heads up’ of the formation of a new UK company ‘to handle our acquisition of LeTourneau. See the attached step plan from Deloitte’, Olsen was asked that Krueger provided the plan because ‘that is why you are choosing the UK company’ -

‘I think it is hard to interpret what somebody was thinking whenever they communicated. But in this instance, I wouldn’t come away from this saying that she believed that the UK company was strictly driven by tax rationale.’

-

(2) In relation to Willis’ email ‘to jot down any concerns’ including the fact that ‘this seems to be done solely for tax planning and therefore may impact our low risk rating’, the question was put to Olsen that the UK group was ‘not enthusiastic about having the LeTourneau acquisition being placed into the UK using the Deloitte tax scheme’:

‘. Once again, ... Vicky Willis is a group accountant. I am not even sure if Vicky Willis was in the UK tax department, and so I think a lot of the issues that Vicky is raising are Vicky Willis’s issues.’

‘... So, I think the issues that Vicky raises were probably very valid concerns on her part and had to be addressed.’ (underlining added)

To the question that the UK group ‘regarded this as an aggressive and rather unappealing transaction’: ‘Well, once again, was it the UK group or was it Vicky Willis?’

Non-tax-advantage considerations for choosing a UK company to acquire LTT

Q: .. the closing of this agreement .. pretty much by five days .. [when] all the work [under Article 6] should really have been done under this May 2011 agreement. So all of the work behind the scenes necessary for those representations and warranties and covenants to be given. That would be quite a considerable amount of work presumably, about the financial status of the company .

A: You are talking about the due diligence?

Q Yes. . all the representations made about the group being purchased and the purchaser, that they are all true. So things have to be evidenced; the due diligence. All that work would have been done, or the obligation waived five days before closing?

A: According to this agreement, that is correct.

Q: And all of that work would have been done either by Joy Global or teams at its direction?

A: Yes. The due diligence would have been done by the various functions of Joy Global . treasury function . tax function . comptrollership organisation . environmental issues . a whole functional team put together to go through this due diligence exercise.

A: The sale between Rowan and Joy Global -

A: - was locked into place. (114)

A: The issue now was where was Joy Global going to assign the agreement. . those directors [of the Appellant on 20 June] . had the ability to say stop.

And they had no obligation to Rowan at this point in time. (114)

Q: And if they had done that on 20 June, Joy Global would have taken as the transfer of [the LTT] stock. It would have had to, wouldn’t it -

A: Not sure. Not sure. My guess -1 shouldn’t say guess, but my assumption would be that Joy Global would then have looked to another of its non-US entities to proceed with their agreement „.’ (115)

Q: But it would be one that was pre-existing?

A: No, not necessarily. ... there is almost always an entity that is created to complete the acquisition. (115)

Q: ... But [the assignment form JGI to the Appellant] was done on closing date, so it was just to make sure that nothing would disturb the main transaction if you like, between the group and Rowan.

A: Yes, I don’t recall that, but that certainly seems logical. (175)

-

(5) Regarding the professional fees to Deloitte of circa $240,000 to $290,000 for their tax advice, Olsen referred to the sum as ‘pretty insignificant’, a ‘relatively small number’ (136), but accepted that ‘it certainly was an amount [Deloitte] were looking for in order to provide us with assistance in putting together the tax structure’ (136). Later in his evidence, he was asked about the fees in relation to the 9-step plan -

Q: You didn’t make the decision in a vacuum, did you? .. you paid over ^ of a million in fees, you knew that if the company agreed to take the assignment and take the precise funding on offer, and to do . steps 1 to 9, it would give the group the benefit that everyone had gone to all this trouble in preparing and paying fees for. You knew, didn’t you, that you would get that benefit for the group? (166)

A: That certainly was one of the outcomes of the decision to acquire LeTourneau. The best outcome of acquiring LeTourneau was the business rationale for the acquisition. But this certainly was one of the outcomes. (166)

-

102. In his witness statement and in his oral evidence, Olsen referred to various non-taxadvantage considerations to support the use of a UK company for the LTT acquisition. A host of questions were put to Olsen to establish what these non-tax-advantage considerations pertained by his own description.

-

(1) Critical mass: Olsen referred to ‘critical mass’ as a reason for preferring a jurisdiction: ‘an entity that has significant critical mass and the ability to generate cash to repay debt’ (143).

-

(2) Synergy perspective: a commercial reason to buy LTT, and then the decision was taken where to place the debt (112-113) -

A: We are going to spend $1.1 billion and this tax piece is going to save a couple of million dollars. So the important part of the [LTT] acquisition was what it was going to be from a synergy perspective on our surface equipment business, as we had to compete with a significantly larger competitor in Caterpillar. The important piece . was to get the product that LeTourneau brought with the acquisition. . The tax piece was an element of the decision process after we decided where the acquisition was going to reside. . Hindsight is always 20/20, but my suspicion is that [suppose] there was none of this [query] of US benefit down the road, we probably would have done exactly the same thing, because the key element was where was that debt going to be placed. (124-125)

A: .. I guess to summarise, my understanding is that in order to make sure that all of the debt associated with the acquisition of LeTourneau did remain [sic?] in the US, Joy Global made the determination that the acquisition was going to be executed outside of the US. (121, underlining added)6

A: The reason we wanted the debt to be outside the US was we had accumulated all ofour borrowings in the US. We had a significant acquisition on the horizon with IMM and we just wanted to be able to diversify our borrowings of the global company. (187-188)

tax by holding assets in non-US subsidiaries (183-184) -

Q: . the repatriation argument doesn’t run. The Deloitte plan . doesn’t give you that repatriation benefit?

A: I don’t know the answer to that. I can’t imagine that Deloitte would come up with a proposal that would put Joy Global at a tax disadvantage.

Q: Well, it didn’t. It absolutely preserved all of the US tax advantage that would come with a US company buying LeTourneau, but it added a UK tax deduction. . the US group got all of the commercial benefits of acquiring LeTourneau. It preserved all its US benefits but it just added on this UK benefit?

A: I am actually not familiar enough with the tax laws to actually address the point you are making....

Judge: . If there are other kind of strategic reasons for placing an entity in a specific jurisdiction, because you said tax is secondary and it is always the strategic reasons for making the plan, so what is behind that thinking in choosing the UK jurisdiction then?

A: My suspicion - once again, we are talking about a decision that took place 10 years ago but certainly part ofthat decision process was probably the ease of incorporating a new company in a particular jurisdiction. That was probably part of it. As I had mentioned, we had a significant critical mass in the UK and so those were the factors that were probably driving the decision to have this acquisition corporation established in the UK.

-

(1) that ‘the tax implications associated with [the LTT] acquisition were not the primary driver of the acquisition’ (105-6);

-

(2) ‘the primary driver as to where the [LTT] acquisition took place was really where was the best place to place the debt associated with the acquisition’ (133);

-

(3) ‘the benefit was to take borrowings and put them outside the US and for this particular transaction, the UK was chosen for that purpose’ (155).

Appellant’S case

-

104. On the first issue as to whether the Appellant had a main purpose of obtaining a tax advantage, Mr Gardiner cited Hansard on the Commons Debates of the predecessor provisions of sections 441-442, and submitted that the provisions were expressly not intended to catch a deduction for the ordinary borrowing costs for commercial investments.

-

(a) In particular, the borrowing cost (on commercial terms) of acquiring shares in a company at an arm’s length price from an outside vendor is not and was never intended to be caught.

-

(b) There is nothing artificial about the financing in this case. It is standard debt/equity financing expressly agreed by HMRC to satisfy thin capitalisation requirements. HMRC’s case here, in the Minister’s terms, is ‘clearly nonsense’.

-

(c) Minister’s comments (in Hansard) were consistent with pre-existing law which had decided in no uncertain terms that the expectation of an ordinary deduction for incurring business expenditure is not an ‘object’ or ‘purpose’ of the transaction at all: Kleinwort Benson and Newton.

-

(d) This appeal is the first case in which HMRC have challenged loan relationship debits arising on debt finance where it is common ground that: (i) the finance was on arm’s length terms, and (ii) the finance was directly used by that company to invest in a commercial acquisition from a third party.

-

(e) In such circumstances, it is frankly impossible to conclude that the interest relief is a main purpose of the loan relationship.

-

105. The answer to the relevant statutory question as regards issue 1 is obvious: JTIAC entered into the loan relationship in order to acquire LTT and that is exactly how the funds were used. Deloitte was engaged in part to ensure that the financing was on ordinary commercial terms and satisfied HMRC of the same in the Advance Thin Capitalisation Agreement. The only UK tax relief arising was the relief for interest paid and on that loan finance. To describe that relief as a purpose to being party to the loan relationship is, in the words of Cross J in Kleinwort Benson ‘ridiculous’ because ‘a deduction for the cost of debt finance is the automatic and ordinary consequence of borrowing for a commercial acquisition’.

-

106. Still less could such debits have been JTIAC’s main purpose. Those amounts represent the arm’s length interest cost for an indebtedness of $550 million used as part finance for an acquisition of an asset worth roughly twice that amount. The very suggestion that JTIAC entered into the debt finance for the purchase of a company worth over $1billion so that it could obtain interest deduction of a value over the four years of less than £9m is ‘absurd’.

-

107. Issue 1 is concerned with whether JTIAC had a main purpose of obtaining a UK tax advantage. Consequently, the US tax position, and in relation to what HMRC describe as a ‘double dip’ is irrelevant. The unallowable purpose envisaged by s 442(3) is expressly concerned with UK tax only. The UK already has robust rules around thin capitalisation as part of the arm’s length test in ITOPA 2010 as well as the anti-arbitrage rules. It is no part of the purpose of the unallowable purpose test in ss 441-442 to act as a fall back in catching any case where a multinational is attracted to make a debt-financed acquisition through a UK company.

-

108. On the second issue of ‘just and reasonable apportionment’, Mr Gardiner submitted that the issue only arises if JTIAC had both a commercial purpose and a UK tax advantage purpose. The question is how much of the debits should JTIAC be entitled to as funding its commercial acquisition? And the answer to that must be that Parliament intended that JTIAC would receive a deduction for its funding costs at a normal commercial rate, no more and no less. Indeed, as agreed in the Advance Thin Capitalisation Agreement, JTIAC should be entitled to the debits in full. At para 12(6) of the Appellant’s skeleton, it states:

‘The purpose of that application [i.e. ATCA] was to confirm the “deductibility of interest arising on related party debt provided to [JTIAC] by [JTI] to facilitate the acquisition of LTT.’ (italics original)

-

(a) Section 441 is looking at a company within the charge to UK corporation tax and at the purpose of the loan relationship that the company has entered into.

-

(b) The existence of the company and its loan relationship are givens.

-

(c) The company is the Appellant and its loan relationship is that created by its borrowing of US$550 million from its parent JTI.

-

(d) One is then required to ask what the Appellant’s purpose is in being party to that loan relationship.

-

(e) The answer to that question is to deploy the funds borrowed of US$550 million in buying the asset, namely the shares in LTT, and to hold the same as an investment which it did throughout.

-

(f) The Appellant’s purpose (let alone its main purpose) is not to pay the interest; that is not its purpose. The obligation to pay the interest is a cost of the funds and is an agreed commercial cost of funds since that is a consequence of the advance thin capitalisation agreement and not a purpose of the Appellant in being party to the loan relationship.

-

(g) It follows that the tax relief for the debits constituted by the payment of the interest cannot be a purpose of the Appellant in being party to the loan relationship, let alone a main purpose.

-

(a) Tax in sections 441 and 442 is UK tax, and all the material about US tax at ‘double dip’ is irrelevant.

-

(b) It is in any event absurd to suggest that anyone would enter into a transaction to acquire an asset costing $1.053 billion for the sake of achieving a tax relief worth just under £9 million over four years and doing so by borrowing $1 billion and being liable to repay the same.

-

(c) If all of the above were wrong and there was a main purpose of securing a tax advantage, and apportionment is an issue, then all of the debits would have to be apportioned to the cost of acquiring the asset, namely the shares in LTT.

-

111. The Appellant’s written submissions post-hearing emphasised aspects of Olsen’s witness evidence (transcript excerpts Appendix A) to state its case. ‘Overwhelmingly’, it was submitted, that ‘the only important factor in considering where to hold the acquisition was where to place and repay debt’; that tax played no important role in the LTT acquisition and was not a strategic driver in the decision to make the acquisition in the UK; the acquisition would likely to have been held in the UK in any event. Other non-tax-advantage drivers were relevant to the decision-making process. The Appellant only approved the transaction at the board meeting on 20 June 2011 because it thought it was a good commercial deal. If any tax benefits were considered, it is only those at the US level, which are not relevant.

-