Introduction

1. The Hinkley Point C nuclear power station in Somerset is to be connected to the national grid by new high voltage overhead transmission lines between Hinkley Point and Seabank. In January 2016 a development consent order was made under the Planning Act 2008 to facilitate the project. The National Grid (Hinkley Point C Connection Project) Order 2016 (the DCO) confers the necessary powers on National Grid Electricity Transmission plc, the respondent in this reference, to undertake the necessary work. It also permits the respondent and Western Power Distribution (South West) plc (WPD) to reconfigure the local electricity network, including by the removal of existing overhead lines.

2. The claimants, Mr and Mrs Cole, are the owners of Spindlewood, a house adjoining the route of the new transmission lines. It is situated on Cadbury Camp Lane, a private road which runs along the top of Tickenham Ridge, above the village of Clapton in Gordano, nine miles southwest of Bristol. Spindlewood is a modern house, built in 2009 and designed to make the most of extensive southwesterly views over North Somerset as far as the Mendip Hills.

3. At present, the view from parts of the garden of Spindlewood and (to a more limited extent) from parts of the house itself, includes the sight of pylons and overhead electricity lines on adjoining land. The location and dimensions of the lines and pylons in the immediate vicinity of the house will change as a result of the project. The existing 132kV overhead lines will be replaced by 132kV underground cables laid in ducts running beneath the claimants’ garden. The existing lines and the four lattice pylons which carry them will be removed and two new T-pylons will be erected to support new 400kV overhead lines carrying power from Hinkley. Neither of the new T-pylons will be on land belonging to Mr and Mrs Cole. They will be taller than the existing pylons, and of a different design, but both will be positioned further from the house than the pylons they replace. One will be about 253 metres from the house on land further down the slope of the hill; the other will be on higher ground to the side of the house at a distance of about 89 metres.

4. This reference arises from a blight notice which Mr and Mrs Cole served on National Grid on 24 January 2020 under section 150(1) of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 (the 1990 Act). National Grid responded with a counter-notice on 4 March 2020.

5. It is not disputed that Spindlewood is blighted land because the compulsory acquisition of rights was authorised by the DCO, but National Grid nevertheless objects to the blight notice on two separate grounds. First, it says that it intends only to acquire rights over part of the claimants’ property, and that the exercise of those rights, taken together with the impact of the project as a whole, will not give rise to material detriment to the property. Secondly, it says that the claimants have not demonstrated that the fact that part of Spindlewood is comprised in blighted land has meant that they have been unable to sell the property except at a price substantially lower than that for which it might reasonably have been expected to sell in the absence of the DCO.

6. It is agreed between the parties that the validity of National Grid’s grounds of objection to the blight notice is to be judged as at 4 March 2020, the date the counter-notice was given.

7. The hearing of the reference was conducted using a remote video platform. The claimants were represented by Ms Isabella Tafur, and National Grid was represented by Ms Rebecca Clutten. Evidence was given by the first claimant, Mr Alistair Cole, and by Mr Peter Mitchell, a chartered surveyor employed by National Grid. The parties also relied on expert evidence on the visual impact the project will have on Spindlewood and on the effect it has had on value. Mr Peter Swift, a landscape architect and urban designer of the firm Planit-IE CMLI, and Mr James Greenland MRICS, a director of Savills, gave evidence on behalf of the claimants. Mr Colin Goodrum FLI, a landscape architect of LDA Design, and Mr Nigel Billingsley MRICS, of Bruton Knowles, gave evidence on behalf of National Grid. We are grateful to all who participated in the hearing for their assistance.

Spindlewood

8. Spindlewood is built on the southern slope of the Tickenham Ridge, with a south-west facing aspect. The Claimants bought the property in 2008 and quickly demolished the house which previously stood there. They replaced it with the current house, designed to their own specification, which was completed by December 2009.

9. The house sits at the top of the plot, with level ground to the sides and at the front. It is separated from Cadbury Camp Lane only by its own short tarmac driveway or forecourt and its gated entrance. The house has three floors, with the main access being from the forecourt to the middle floor with stairs then leading up to the first floor and down to rear garden level. It has six bedrooms and was designed so that the master bedroom and bathroom on the first floor and the open-plan kitchen and living area on the middle floor enjoy attractive views of the Mendips (c.13km) and, in good visibility, the Quantocks, some 45-50km beyond. To capitalise on these views the south facing rooms have floor to ceiling glazing and those on the middle floor have sliding doors opening on to a south-facing balcony. Two guest bedrooms on the lower ground floor also have sliding glazed doors which open onto decking at garden level.

10. Off the driveway to the east of the house stands a garage or outbuilding on two floors, with a garage for one vehicle and a carport at ground level and ancillary living accommodation on the upper floor.

11. Spindlewood has a gross internal area of 400.3 m2 (4,307 sq.ft). This includes the first floor of the garage building but not the garage itself which extends to 99.7 m2 (1,073 sq.ft) when measured on the same basis. The boiler room/store and WC (which are externally accessed) are 16.0 m2 (172 sq.ft) in area.

12. At the rear of the house the garden of 1.076 hectares (2.66 acres) extends down the slope for about 200m, tapering as it goes. The garden is informal and comprises a wide upper terrace, which then falls gradually away from the house, becoming narrower before reaching a wooded area at the bottom. The rear garden is entirely grass with individual mature trees and wooded boundaries along the south-east and north-west sides. A small ‘golf green’ has been cut into the slope at the end of the grassed area, and an area on the boundary is used for bonfires. From this area at the bottom of the garden there are direct views from and of the neighbouring house to the west, Deep Acres, and its garden.

13. Cadbury Camp Lane is a private road running west from Whitehouse Lane which runs up to the top of Tickenham Ridge from Clapton in Gordano. Spindlewood is the first house at its eastern end. The properties along the Lane are generally large residences in a variety of styles, many of which have been built quite recently on the sites of earlier smaller dwellings. The slopes of the Ridge are well wooded, giving the Lane a secluded feel but limiting the views over the countryside from some of the houses. The Lane runs along the top of the Ridge and, in general, the properties on the southern side have the better views; those on the northern side look towards Redcliff Bay and Portishead. The M5 runs along the base of the Ridge to the north, making properties on that side (especially at the western end) noisier than those, like Spindlewood, on the southern side.

14. A public bridleway follows the lane and a public footpath passes to the east of Spindlewood running south-east from Cadbury Camp Lane through a narrow area of woodland known as Moggs Wood. There are no direct views into the property from Cadbury Camp Lane, and only glimpses in are possible from the public footpath, through existing vegetation. The parties agree that it enjoys a secluded and private location.

15. Beyond the south-eastern boundary of Spindlewood is a large field, sloping steeply downhill towards farm buildings at the bottom. The field is too steep for easy arable cultivation and is used for grazing livestock. Moggs Wood runs along the northern and eastern edges of the field.

The existing electricity infrastructure

16. Two existing 132kV overhead powerlines belonging to WPD converge in the field adjoining the south-eastern boundary of Spindlewood. The lines are referred to as the F route and the W route, and they are supported by traditional 23.5m steel lattice pylons, three of which stand sufficiently close to the claimants’ property to be visible from parts of it. Two of these pylons, designated F22 and W19, stand in the field adjoining the garden. A third pylon, F21, stands in a field adjoining Cadbury Camp Lane to the east of the house, north of Moggs Wood. None of the existing infrastructure stands on or crosses the claimants’ land.

17. The location of the existing pylons and the extent to which they and the overhead lines which they support are visible from the claimants’ property at different times of year was the subject of evidence from the landscape experts, which was substantially agreed.

18. The pylon closest to Spindlewood is F21 which stands next to Cadbury Camp Lane directly east of the house. The distance from the centre of the base of the pylon to the nearest point of the house is 50m. The experts agree that it is not visible from within the house itself in summer and in winter it is visible only from the kitchen window. It is also occasionally visible in summer from some lower parts of the garden and in winter, additionally, from the driveway between the house and garage.

19. The overhead lines running downhill, south-west from F21 towards F22, are 45m from the house at the closest point and are not visible from the house in summer. They are visible in winter from the kitchen window and from the side window of a bedroom at the eastern end of the house on the upper floor. They are also visible between trees and above the garage in summer and winter from the driveway and from the middle area of the garden.

20. Pylon F22 is downhill from F21 and stands in the grass field beyond the south-eastern boundary of Spindlewood, 175m south of the closest point of the house. It is not visible from the house in summer. In winter there are glimpsed views through trees from the master bedroom on the middle floor. It is also visible from the upper, middle and lower parts of the garden in summer and, to a greater extent, in winter.

21. A short stretch of the overhead lines running further south from F22 is visible from the garden in summer and winter. It was originally agreed that these lines were not visible from within the house although Mr Goodrum changed his opinion on that matter and thought that they were visible to some degree. We are satisfied that if there is any visibility from within the house it is not significant.

22. The highest points of pylons F21 and F22 are 153.2m above ordnance datum (AOD) and 128.75m AOD respectively.

23. Two pylons on the W route are visible from the claimants’ property. W19 is 150m south east of the house. It is not visible from within the house but can be seen occasionally from lower parts of the garden in summer and winter. W20 is 225m downhill to the south of the house and 122m AOD. It is only visible from the garden in glimpsed views through trees in winter.

24. In summary, of the existing infrastructure in the vicinity of Spindlewood neither F21, F22, nor the overhead lines are visible from principal rooms of the house in summer, but in winter they can be seen to a limited extent from the kitchen window and one smaller bedroom. Both these pylons and their overhead lines are visible from parts of the garden year-round, to varying extents.

25. Our own impression having visited Spindlewood on a sunny day in February is that any visitor would be aware on arriving in Cadbury Camp Lane that there is electrical infrastructure in the immediate vicinity. At Spindlewood itself, overhead wires are clearly visible from the driveway. Views of lines or pylons from within the house are very limited and not at all obtrusive, but when walking in the garden it is again clear that there are pylons and overhead wires quite close by on neighbouring land.

National Grid’s powers and the works under the DCO

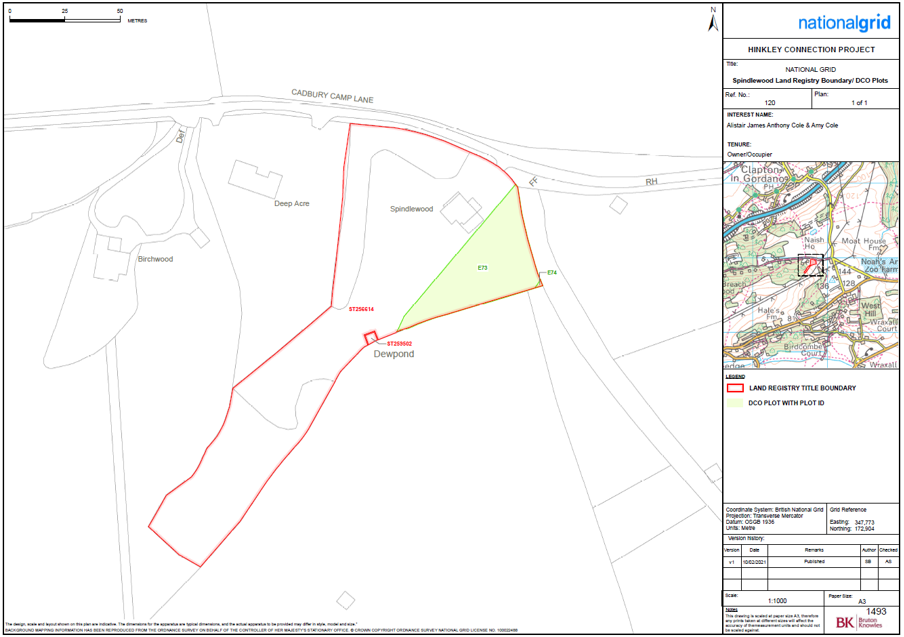

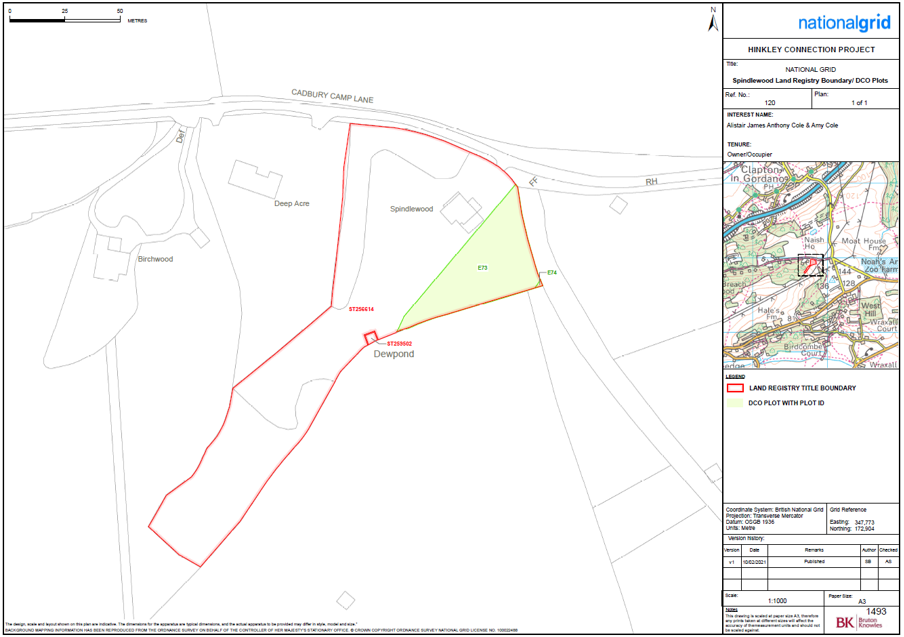

26. The DCO confers very extensive powers on National Grid to enable it to undertake the Hinkley connection project. They include power to acquire rights over two parcels of land in the eastern part of the grounds of Spindlewood, identified as plots E73 and E74, which together comprise 1,689sqm (0.42 acres) or approximately one sixth of the total area of the claimants’ land. The two plots adjoin the wooded south-eastern boundary and include part of the upper lawn, part of the drive, and the area occupied by the garage. No part of the house itself is included in the two plots but they come very close to it; no land (as opposed to rights over land) is authorised to be acquired. The reference plots are shown on the following plan (the garage is not shown on the plan).

27. The rights which National Grid is entitled to acquire over plots E73 and E74 can be exercised both by it and by WPD. They include the right to enter the land with or without vehicles to construct and use, and to maintain and replace, the authorised installations; to fell or lop trees and bushes; and to obtain access to adjoining land. They also enable National Grid to require that the owners of the two plots do nothing on their land which might interfere with the authorised development or access to it.

28. The authorised works are described in detail in the DCO and are shown on approved works plans. They were designed to be undertaken in stages between 2020 and 2025, and the works relevant to this reference are comprised in stages 4 and 10, each of which has a construction and an operational phase.

The stage 4 works

29. The stage 4 works include the laying of new underground high voltage 132kV electricity cables in two sets of ducts beneath part of the claimants’ land to supply the local network. This is required so that the pylons which currently support the lines can be removed and replaced by the new pylon line from Hinkley. These works had not commenced by 4 March 2020, the date of NG’s counter-notice, but they were complete by September 2020.

30. The DCO required that before the stage 4 works commenced a site-specific mitigation scheme for Spindlewood was to be approved by the local planning authority to mitigate all the impacts of construction activities including noise, dust, vibration, and visual effects. The claimants’ property was one of only a handful along the route of the Hinkley project for which site-specific mitigation measures were required. The stage 4 measures were signed off by the authority in November 2019, four months before the material date.

31. The preferred route of the new underground cables was shown on the works plans, along with limits of deviation within which the DCO authorised the laying of the cables if it proved necessary to depart from the preferred route. The plans showed two lines of cable ducts passing beneath the claimants’ drive and their garden on either side of the garage. The closer of the two lines was to come within 18m of the side wall of the house, while the further was to be within 35m, both at a depth of 8m below the surface. In practice the final route of the cable ducts was diverted to avoid unfavourable ground and only one of the two cable ducts runs beneath the claimants’ property, between the front of the garage and the house. The other duct was drilled through Moggs Wood to the east of the boundary.

32. To facilitate the laying of the new cables, the DCO authorised the creation of a temporary drilling pit or compound in the field 68m to the south of the house. The duct route was drilled from the compound by horizontal directional drilling. A second compound was also established 95m to the north of Spindlewood, on the opposite side of Cadbury Camp Lane into which the drill would emerge.

33. The establishment of a much larger temporary construction compound on the corner of Cadbury Camp Lane was also provided for by the DCO, as was a temporary bell-mouth on the Lane to enable access to the compound by HGVs. In the event, these facilities were not required for the stage 4 works (although they may yet be for stage 10).

34. Access to the drilling launch compound was not permitted from Cadbury Camp Lane itself and had to come from the south. The DCO authorised the construction of a new cross-country haul road in the field to the east of Spindlewood to serve both the stage 4 and stage 10 works. It also authorised the removal of vegetation around the property, although as matters transpired none was required as part of the stage 4 works.

35. The powers conferred by the DCO were intended to be comprehensive and it would have been lawful for National Grid to excavate the route of the new ducts from the surface or even to demolish the claimants’ garage to facilitate the works. In fact, as is now known, stage 4 involved no above-ground works on the claimants’ land. The only visible signs of the works within the claimants’ boundaries were a stile created to enable access by foot half-way down the garden, some small marker flags along the line of the drill and a vibration monitor.

36. The DCO also allowed National Grid temporarily to stop up Cadbury Camp Lane and to break up its surface without the provision of alternative vehicular access if necessary.

37. Construction of the terminal drilling pit commenced in May 2020, and the launch compound in June 2020. The drilling works were estimated to be completed within 6 to 8 weeks and they were finished in August 2020, with only cable pulling and restoration after this date. This had been completed by the time of the Tribunal’s inspection, and all that remained to be seen from the claimants’ property was a small area of hard standing in the adjoining field, an access track leading to it, and a stock proof fence.

38. The ducts and cables installed as part of the stage 4 works lie at a depth of 8m below the surface of the claimants’ garden and they will be concealed throughout their operational use. If access is required to repair or replace defective cables it will be taken from one or other of the original drilling compounds and it is very unlikely that the route will ever need to be excavated from the surface. The only restrictions of any practical significance which the continuing prohibition of works above the route of the cables may place on the claimants will be to prevent them from enlarging their garage or installing a swimming pool in the area of lawn in front of it. An extension to the garage was no more than a theoretical possibility and although we were shown plans for a pool in that location it was not suggested the project had progressed further than the drawing board. There appeared to us to be sufficient space on the other side of the house for a pool if the claimants wished to build one.

The stage 10 works

39. The stage 10 works are yet to commence but when they do, they will not take place on the claimants’ land. They will begin with the removal of the existing 132kV overhead power lines and pylons on the W route, followed by the installation of a new 400kV overhead power line, and will conclude with the removal of the power lines and pylons of the F route. The new overhead lines will be supported by “T” pylons, each about 35m to 37m tall. T-pylons are considered by National Grid to be less obtrusive than traditional lattice pylons and the Hinkley project will feature their first use in this country. The T-pylons closest to Spindlewood are identified on the works plans as LD86 and LD87.

40. Pylon LD87 will be east of Spindlewood, in the same field as F21 (which will be removed) but further from the house. F21 was 50m from the house at its closest point, but in its preferred position the centre of LD87 will be 89m away and the closest point of the T supporting the cable will be 73.5m from the house. LD87 will be 50% taller than F21, at 35.17m compared to 23.5m, and the top of the new pylon will be about 10m taller AOD.

41. When it is erected, pylon LD86 will be south-east of Spindlewood in the same field as F22 and W20 (which will both be removed). LD86 will be more than 250m from the house and further away than the existing pylons. The field falls sharply away from Spindlewood and although it will be 32.26m tall the top of LD86 will be a few metres lower AOD than the top of F22 which is only 23.5m tall.

42. The works plans show the preferred location of the new pylons but the DCO authorises their installation within certain limits of deviation, which are also shown on the plans. Although these limits would appear to allow LD86 and LD87 to be built quite a lot closer than their preferred locations, in practice the knock-on effects of re-locating one of a line of pylons extending for 57 km make it unlikely that there could be any significant change in their location. The practical constraints on the positioning of the pylons were considered in National Grid’s environmental statement submitted when it applied for the DCO, and it was noted that they would only be able to deviate by a maximum of about 10m sideways from the preferred route. On the day before the hearing of the reference, and after discussion with its main contractor, National Grid gave an undertaking to the claimants that the location of the new pylons would not deviate by more than 1 metre in any direction from the preferred location shown on the DCO works plans. This assurance was not available in March 2020 when the counter-notice was given.

43. The stage 10 works will require the removal of trees and hedges from the narrowest part of Moggs Wood and the extension of the temporary haul road to enable access for plant and machinery coming from the south. A right given by the DCO to close Cadbury Camp Lane for temporary periods will also need to be exercised to enable the new cables to be strung safely between LD86 and LD87.

44. Information in the public domain in January 2020 suggested that the stage 10 works were likely to continue until mid-2025. National Grid now expects the works to commence in the Tickenham area in May 2021 and says that they should be complete in 2024 (although at the date of the hearing there had been some slippage in the timetable for obtaining approval of mitigation works from the local planning authority). The work will not be continuous but will involve distinct operations being carried on sequentially at each of the existing pylons, to remove them, and then at the sites of the new pylons to create piled foundations and to install and commission the new structures. The W route is scheduled to be dismantled in 2021 and the F route in 2023. Installation of the new pylons is intended to be completed in about July 2023. Reinstatement works are schedule to be complete by December 2024.

45. We received no written evidence concerning the duration of the various operations but Mr Goodrum told us he had made enquiries and understood that once the overhead lines had been removed the demolition of each of the existing pylons would be completed in a single day, although their removal and site reinstatement would take longer. The new pylons will be fabricated off site. A piling rig will be required to create the foundations and the pylons will be erected using a crane. We think it unlikely that either of these operations will take more than one or two weeks at each pylon site.

46. Once the new pylons have been installed, they will no doubt require occasional maintenance. Mr Cole told us that he had not been aware of maintenance being undertaken to the existing pylons (although it has occurred) and we think it unlikely that work to the new pylons during their operational life will be any more intrusive.

The issues

47. National Grid’s counter-notice objected to the claimants’ blight notice on the grounds in section 151(4)(c) and (g), 1990 Act (as modified in relation to the acquisition of rights by section 151(5)).

48. Ground (c) applies if an authority proposes to acquire rights over part only of a hereditament and does not intend to acquire any other part of the hereditament unless compelled to do so. Unless the rights can be acquired over the part concerned without significantly disadvantaging the remainder of the hereditament the authority may nevertheless be compelled to acquire the whole hereditament under section 8, Compulsory Purchase Act 1965.

49. Where the hereditament over which rights are sought is a house, ground (c) is supplemented by section 153(4A), 1990 Act and the Tribunal must consider whether the rights can be taken without material detriment to the house. In the case of a park or garden belonging to a house, the question is whether the rights can be taken without seriously affecting the amenity or convenience of the house. By section 58, Land Compensation Act 1973, the question whether material detriment will be caused to Spindlewood is to be judged by reference to the effect of the project as a whole, and not simply the effect of the acquisition of the rights over the claimants’ garden.

50. If the rights cannot be acquired without material detriment to Spindlewood, National Grid will be required to acquire the whole of the claimants’ property. The burden of proving the matters necessary to make out ground (c) falls on National Grid.

51. Ground (g) applies if the claimants cannot show that, in consequence of the fact that Spindlewood was comprised in blighted land, they were unable to sell it at the date of the counter-notice except at a price substantially lower than it might reasonably have been expected to sell for if no part of it had been comprised in such land. Where, as in this case, the compulsory acquisition of rights is authorised by a DCO, there is no requirement for the claimants to show that they had made reasonable endeavours to sell their property (paragraph 24, Schedule 13, 1990 Act).

52. In O’Rourke v Keuper Gas Storage Limited [2018] UKUT 160 (LC) at [16] the Tribunal proceeded on the basis agreed between the parties in that case that:

“… the price at which the property might reasonably have been expected to sell, had it not been blighted land, is to be ascertained by considering the response of a hypothetical prudent purchaser who, it should be assumed, would have made reasonable inquiries and been aware of such information as would have been disclosed.”

53. Although there was some debate in the evidence about what information would have been available to a hypothetical prudent purchaser in March 2020, and what that person’s reasonable inquiries would have consisted of, we did not understand there to be any disagreement that the same approach is required in this case.

54. We must therefore consider whether the claimants were unable to sell their house in March 2020. It was not then on the market, but we must nevertheless consider whether and at what price it could have been sold, and whether that price would have been substantially lower than the price for which it might reasonably have been expected to sell at that date if no part of it had been blighted by the Hinkley connection project.

55. One difference between this case and O’Rourke is that here the claimants did not put Spindlewood on the market before serving their blight notice, nor had they yet done so by the time of National Grid’s counter-notice which fixes the material date at 4 March 2020. The claimants rely on marketing advice which they received from a number of sources in 2019, and on their experience in marketing Spindlewood after July 2020. We will therefore have to consider what weight to place on that advice, and what we make of the marketing of the property after the material date.

Ground (c) - material detriment

56. In determining whether to uphold an objection on ground (c) the Tribunal is required to consider whether the rights sought over Spindlewood can be taken without material detriment to the house or, to the extent that they are being acquired over the garden, without seriously affecting the amenity or convenience of the house.

57. The expression “material detriment” has been understood in this context as meaning that the property subject to the rights (or after the acquisition of part) would be “less useful or less valuable in some significant degree”. That gloss is taken from the decision of the Lands Tribunal (J.S. Daniel QC) in Ravenseft Properties Ltd v London Borough of Hillingdon (1969) 20 P. & C.R. 483 in a case concerning the compulsory acquisition of the driveway and most of the garden of a house, but not of the house itself. The Tribunal rejected the suggestion that there could be no material detriment unless compensation would not be an adequate remedy for the severance of part of the property, explaining instead (at 493) that:

“It seems to me to be intended rather that the significance or materiality of the detriment should be considered and determined by reference to its nature and degree, ...”

58. The parties agreed that in determining whether material detriment will be caused to Spindlewood it is relevant to consider both the construction phases of the project and its operational effects on the property once it has been completed. The validity of the ground of objection is to be assessed as at the date of the counter-notice, when very little, if any, of the relevant work had commenced. The effect of taking the rights is to be assessed by considering how they would realistically have been expected to be exercised based on the information available at the material date, rather than by assuming the maximum inconvenience which could lawfully be caused by their exercise, no matter how implausible it may be that they would be exercised to that extent. Ms Tafur suggested that works carried out after 4 March 2020 can be taken into account as indicative of the likely exercise of the powers for the purpose of ground (c). We agree.

59. The claimants’ case on material detriment focussed to a large extent on the adverse visual impact of the works on the amenity of Spindlewood, during both the construction and operational phases. They relied additionally on the adverse consequences of the works for their privacy, especially during the construction phases. Other negative consequences of the works which they asked the Tribunal to take into account were the felling of trees; noise, dust and air quality during construction; the inconvenience which would be caused to access by temporary stopping up of Cadbury Camp Lane; the prohibition of development on part of their property, including any extension to the garage or the creation of a swimming pool; and, following the commissioning of the new lines, what they referred to as “the perceived health risks from electromagnetic fields”.

Visual amenity and privacy

60. Although they disagreed in their assessments of the severity of the adverse effects the works have or will have on the visual amenity of Spindlewood, Mr Swift and Mr Goodrum, the landscape experts, were largely able to agree what those effects were. They had each visited the property during the summer of 2020 while the stage 4 works were being undertaken and in December 2020 by which time they were complete. They had taken photographs from a number of viewpoints and had used these, together with information about the new pylons to be installed in stage 10, to prepare photomontages showing how the completed works would look from different locations in the house and garden.

61. The construction phase of the stage 4 works had been completed during the summer months and nothing of significance remained to be seen from any of the expert’s viewpoints when they returned in winter. It had not proved necessary for boundary trees or vegetation to be removed and the only work undertaken above-ground on the claimants’ property had involved surveying and monitoring.

62. While they were being undertaken the works conducted from the drilling compound on the northern side of Cadbury Camp Lane were visible to someone standing at the kitchen sink, but could not be seen from any of the principal rooms or from the garden; nor could the northern haul road be seen. One of Mr Swift’s viewpoints looked north from the driveway at the front of the house and the works to the north do not appear on his photograph from that location although there may have been parts of the drive from which they could have been spotted. The distance between the closest points of the compound and the house is 95m.

63. The experts agreed that the haul road running south from the southern drilling compound could not be seen from the house in summer and had not been seen by them during their winter visits. In winter, traffic moving on the haul road may be visible from the top of the garden although none had been witnessed by the experts. The southern drilling compound itself, and depending where the viewer was standing, the vehicles, equipment, and acoustic fencing associated with it, were visible in summer through the boundary trees from the area of the lower garden in the vicinity of the golf green and the bonfire site, but not from closer to the house. The mature boundary vegetation did a good job of screening activity in the field beyond, but the photographs taken by Mr Goodrum (though not those taken by Mr Swift) show that the activity in the compound was apparent at least from the higher ground above the golf green.

64. There was no suggestion that, once operational, the stage 4 works have any adverse effect on Spindlewood’s visual amenity. After the cables were installed in their underground ducts, the drilling compound decommissioned and the land reinstated, there is nothing to indicate that any significant engineering activity has been undertaken in the adjoining field.

65. The effect the stage 4 works had had on the privacy of Spindlewood was also considered. The landscape experts agreed that the property generally has a secluded feel although Mr Swift acknowledged, as we had observed on our inspection, that at least in winter there are good views from the adjoining house and garden into the claimants’ garden, especially towards the lower end. Mr Cole gave evidence, which was not challenged, that during the stage 4 works there had been occasions when workmen had appeared in the garden, or had asked if they could simply ‘jump the fence’ to gain access. As a result of these intrusions, and because the claimants choose not to have blinds or curtains on the upper floor of the house, he felt the need to check the garden for people before using the upstairs areas of the house. On one occasion a drone had flown over the garden while the route was being surveyed, causing Mrs Cole to leave the balcony. In summary, he said, “the prospect of interference with our privacy significantly impacts on our use and enjoyment of our home.”

66. As for the stage 10 works, it is agreed that during the construction phase filtered views of the demolition of the existing pylons and of the cranes and piling rigs used in the erection of the new pylons will be available from the garden, but there will be no views from the principal rooms of the house.

67. Once it is erected, pylon LD86, sitting at the foot of the slope beyond the south-eastern boundary and more than 250m from the house, will not be visible from within the house. The pylon will be visible through the trees in winter from the middle and lower part of the garden.

68. Pylon LD87 will not be visible from within the house. Although it will be much closer than LD86, it will only be seen from the bottom of the garden looking back up the slope and across the boundary. This will be by far the clearest view of any of the new pylons and it is likely that the whole of the top half of the pylon, including the diamond shaped gantries which dangle from the pylon’s arms and support the cables themselves will be visible above the tree line of Moggs Wood in winter and in summer.

69. The new overhead power lines between LD86 and LD87 will be visible from the side window of one of the bedrooms on the upper floor of the house (the same bedroom from which cables can currently be seen). The power lines north of LD86 will also be visible from the bottom of the garden.

70. These assessments of the visual impact of the new pylons assume that they will be constructed on National Grid’s preferred route. It was not suggested that deviation from the preferred position by up to 10 metres required any alteration in the assessments.

71. Both experts referred in their reports to the environmental statement which had been submitted by National Grid as part of its application for the DCO. This suggested that, on a worst-case basis, Spindlewood would have views of the stage 4 and stage 10 construction operations (although it did not distinguish between them) across a large extent of the view, and that during construction, during the subsequent operation of the new lines, and after 15 years, the impact on landscape and visual effects would be “moderate adverse”. As Mr Cole pointed out, these assessments were made without the assessor ever visiting the claimants’ property. They were broadly adopted by the DCO examiners although they considered that the assessments under-estimated the beneficial effect of the removal of the existing pylons and the erection of the new pylons at a greater distance from the house.

72. The experts also undertook a “residential visual amenity assessment” (RVAA) based on guidance provided by the Landscape Institute. An RVAA is an analytical tool often used in planning decision making specifically to judge the effect on the visual amenity of private residential property of changes in landscape. If the RVAA threshold level is reached the methodology advises that the predicted effects on residential visual amenity will be of such a nature and magnitude that they have the potential to affect living conditions and ought therefore to be taken into account in the planning balance. The Landscape Institute’s guidance identifies this threshold level using terms such as “overbearing” or “overly intrusive”. The experts were very familiar with this method of assessment and we agree that it provides a useful methodology, but care is required to ensure that an assessment that the RVAA threshold level has been reached is not substituted for the statutory question whether the acquisition of the rights in question have caused material detriment to the claimants’ land.

73. For the claimants, Mr Swift identified seven key viewpoints to illustrate his assessment and focussed on three of these as showing what he considered the most adverse impacts. These were the views from the master bedroom on the upper floor of the house (VP4), from the drive between the house and the garage looking east (VP7), and from the bottom of the garden looking across the south-eastern boundary (VP1). For National Grid, Mr Goodrum placed greatest emphasis on the views from the principal rooms of the house and the upper garden although he also provided photographs taken approximately from Mr Swift’s viewpoints. In particular, Mr Goodrum included panoramic views and photomontages from the bottom of the garden (his VP6).

74. Mr Swift’s initial assessment was that, on the assumption that the works were carried out in National Grid’s preferred locations, they would have a moderate effect on Spindlewood by reason of visual impact and privacy. They would not reach the Landscape Institute’s RVAA threshold. However, if the works were relocated to a position which Mr Swift understood was the closest to the house permitted by the DCO limits of deviation, he considered that the works would have a serious impact on the amenity and convenience of Spindlewood and would be materially detrimental. He prepared photomontages illustrating his concerns, which showed the new pylons to be very much more prominent and intrusive in views from the house and garden if they were assumed not to be on National Grid’s preferred locations but to have been constructed instead with the base of the pylon at the limit of deviation.

75. Further evidence from Mr Mitchell concerning the practical consequences of the limits of deviation caused Mr Swift to revise his assessment. He acknowledged that, contrary to his original understanding, the base of the pylons themselves could not be built at the limit of deviation, since that would cause them to overhang the limit and would fail to allow for movement of the overhead lines caused by the wind. In practice National Grid also allows an additional 5.3m clearance between the limit of swing of the overhead lines and the limit of deviation permitted by the DCO.

76. Mr Swift’s final assessment was that, ccumulatively, the scheme would have a significant impact on the usefulness and value of Spindlewood, and a serious impact on its visual amenity. Taken in isolation, the visual impact and privacy implications of the stage 4 works had had only a moderate adverse effect on the property during the construction phase and had not reached the RVAA threshold. The same could not be said of the stage 10 works, at least during winter months. Mr Swift anticipated that the stage 10 construction phase would have a significantly adverse effect on the value and use of Spindlewood and a serious effect on its amenity during winter if completed along the preferred route. In aggregate the construction and operation of the stage 10 works would, in his view, give rise to a “profound impact” on the claimants’ use of the property, particularly in winter.

77. We do not accept Mr Swift’s assessment of the seriousness of the visual impact the works have had, or will have on Spindlewood. He and Mr Goodrum agreed that, from the principal rooms of the house there were no perceptible views of the existing overhead lines and pylons and that the stage 4 construction works had not been visible. He also thought that, seen from the main living space, assuming the stage 10 works take place in winter, loss of leaf cover would “potentially allow minor glimpsed views of the uppermost portion of the construction works to the T-pylon, although heavily filtered by tree branches”. These were realistic assessments from the most important viewpoints within the house. They ought, we consider, to have led to the conclusion that the works would have only a moderate or even negligible visual impact. The significance of these important and substantially unaffected views, which the house had been designed to exploit, was trumped in Mr Swift’s assessment by views from much less prominent vantage points. But we consider Mr Swift attributed too much significance to those views.

78. The view from VP7 over the top of the garage from the driveway at the front of the house is not an important one and, in any case, it already features overhead lines in winter and summer. The introduction of a new pylon into this view, visible through trees in winter but not in summer, will make little difference to the amenity of the property as whole.

79. The view across the south-eastern boundary from the furthest end of the garden (VP 1) cannot sensibly be described as a “primary viewpoint” in terms of the amenity of the house and garden. We were not persuaded by Mr Swift’s suggestion that the views of the stage 4 works were seriously adverse from this location, which seemed to us to be disproved by Mr Swift’s own photographs. VP1 is certainly the position in the garden from which there will be the clearest view of the new pylon LD87, as Mr Goodrum’s panorama demonstrated. But that area is already the least private part of the garden, as it is overlooked from the neighbouring property; it also slopes quite steeply with the only level section being the small golf green, and it adjoins the site of the bonfire. Someone who chose to walk round the garden, or to look up from constructing a bonfire or practicing putting, would take in the views from this area, but we do not think they would go to that part of the garden to enjoy views of the surrounding countryside or for any other recreational purpose. In our judgment the weight which Mr Swift attributed to this location was not justified.

80. Nor do we consider that the emphasis Mr Swift placed in his overall assessment on the construction phase impacts of the stage 4 and 10 works was merited. He was obviously aware that these works would be temporary, and appreciated that they would not be continuous, but he did not seem to us to have made any estimate of how long the erection of the new pylons and the removal of the existing structures would take. In cross examination he referred to periods of one, three or six months, and said he had to assume a worst case. It was not clear whether he meant that his RVAA assessment had assumed work on each of the pylons would take as long as six months but, if he did, we think that would be a significant over-estimate (as Mr Swift himself appeared to acknowledge when he said that the worst case may be over-pessimistic in this context).

81. In his oral evidence Mr Swift also mentioned that he considered the change from traditional steel lattice pylons to modern “T” pylons, which he described as “alien to the landscape”, would in itself be adverse. That was not a factor which had contributed to his original appreciation of the consequences of the works and we do not give it weight in our own assessment. The new form of pylon has been designed with a view to being less obtrusive and the photomontages we were shown did not suggest to us that the LD86 and LD87 will be damaging when compared to the existing infrastructure.

82. As for privacy, we understand the irritation which is likely to be caused to a householder if contractors are found unexpectedly in their garden, even where their presence is lawful, but we do not think the occasional episodes described by Mr Cole add significantly to the assessment of detriment. Mr Cole’s subjective views on privacy seemed to us to have been adopted uncritically by Mr Swift and we do not accept his evidence that the works have had, or will have, a “profound impact” on the claimants’ enjoyment of their home as a result of their being observed in the house or garden by contractors on the opposite side of the boundary.

Other amenity considerations

83. Although the visual impact of the works was the focus of the expert evidence, Mr Cole also referred in his evidence to noise, to the need to keep windows closed in summer during the works and the consequences for the temperature indoors, and to the intermittent temporary closure of Cadbury Camp Lane. We take these into account, but we bear in mind that the stage 4 works were the subject of site specific mitigation measures to limit the impact of the construction works, and the stage 10 works will have their own separate mitigation scheme. The construction phase will be relatively short and we do not consider that the real but temporary inconvenience which will result to the claimants adds significantly to the assessment of detriment.

Conclusion on ground (c)

84. Our assessment of the visual and amenity impact of the works accords with that of Mr Goodrum. The stage 4 works had a modest adverse impact between May and September 2020. The stage 10 works will also have a modest adverse impact in short episodes spread over four years. Once the works are complete they will not be significantly more visually intrusive than the existing electricity infrastructure. At no stage will the effects on the claimants’ property amount to material detriment or seriously affect the amenity or convenience of the house in the sense required by ground (c). Ground (g) - the impact of the scheme on the claimant’s ability to sell Spindlewood

84. We now turn to the impact of the scheme on the ability of the claimants to sell Spindlewood. We will firstly examine the evidence of the valuation experts and consider the information available to prospective purchasers in March 2020. Our analysis of the marketing advice received by the claimants in 2019 and more recent marketing activity then follows as a separate topic. Although we will bear all of the evidence in mind we will treat it in that way because, on the claimants’ case at least, Mr Greenland specifically stated that he did not have regard to the views of other valuers (although he suggested that his own views on the unblighted value of Spindlewood were consistent with advice received by the claimants from other sources) or on the response of the market when the property was offered for sale. Mr Billingsley did address the question of why Spindlewood had failed to sell in 2020 but it formed little part of Mr Greenland’s analysis.

Mr Greenland’s evidence for the claimant

85. Mr Greenland is a director of Savills based at their Bristol and Bath offices. He specialises in the valuation of prime residential properties. He had valued a number of properties on Cadbury Camp Land and in the vicinity. Mr Greenland’s view is that there are only limited material differences in what is authorised by the DCO and the works National Grid says it plans to undertake. He recognises that exactly how the property will be impacted by the works is unknown but nevertheless he says there will be an effect during construction and after completion such that the value will be adversely influenced.

86. Mr Greenland referred in his evidence to four lines of enquiry that he considers relevant in assessing the impact of the scheme on the value of the property. They were the sale of Cauldhame, a substantial house and estate at Sheriffmuir near Dunblane in Scotland; the “need to sell” scheme operated by HS2; a 2003 academic paper concerning the impact of electricity infrastructure on property values; and finally, negotiated settlements of compensation claims related to electricity infrastructure.

87. Cauldhame is a seven-bedroom house with three cottages, gardens, grounds, grassland and woodlands, in all extending to 208 acres. At first sight the circumstances at Cauldhame appear similar to those at the property. In February 2010 a wayleave was granted for the construction of a new 400kv power line to replace an existing lower voltage line. The new line would be situated on part of the property. The corridor along which the line would be routed was defined but the design and precise location of the 50m tall pylons within that corridor was not known. Significantly, the corridor was some 400m from the house and there were some direct and elevated views of the nearest point of the corridor but in views from the principal rooms the corridor was more distant.

88. The property was initially marketed in November 2010 at a guide price of £2,000,000. The selling agents (Savills) informed Mr Greenland in correspondence that the wayleave deterred prospective purchasers and that, over time, the guide price was successively reduced until it reached £1,325,000. The sale of the property was eventually concluded in January 2013 at £1,150,000. Construction of the power line and associated pylons took place in 2015.

89. The former owner was unable to reach agreement with the appropriate authority regarding compensation and the matter was referred to the Lands Tribunal for Scotland for resolution. One aspect to be considered was the value of the property absent the grant of the wayleave and the parties’ rival positions were that the property was worth £1,900,000 and £1,500,000 respectively. The case was settled before the hearing at a figure which was not revealed, but Mr Greenland observed that the reduction in value resulting from the grant of the wayleave was either £350,000 or £750,000 depending on which view of the unblighted value was used as a starting point. The sale price therefore represented a reduction of 23.3% or 39.5% from the rival valuation figures.

90. Mr Greenland acknowledged that Cauldhame is a different style of property and in a markedly different location but said that the evidence demonstrated the significant combined impact that a new power line and the uncertainty that this engenders, together with the prospect of disturbance from its construction has on the value of a prime property. He suggested that it was for this reason that a number of large infrastructure projects have discretionary blight schemes, some of which he then went on to consider.

91. Mr Greenland admitted that he had not been to Cauldhame or had sight of any photographs of it, other than those in the marketing particulars. He acknowledged its potential for a holiday letting business and the possibility of deriving revenue from shooting and other leisure pursuits and considered it likely that these business interests would also be diminished by the scheme but was unsure by how much. We agree with Mr Greenland that it is reasonable to conclude that the presence of the Cauldhame scheme may have deterred prospective purchasers, but whilst the context is superficially similar to the circumstances at Spindlewood, the property itself had a number of significant differentiating factors, not least its size and the relative positions of the pylons. We do not know the compensation agreed, nor do we know to what extent the original guide price or the subsequent valuations before the Lands Tribunal were reliant on the income from the various business opportunities. In summary, while it indicates that the expectation of a substantial engineering project being conducted on a small rural estate is likely to have an adverse effect on its saleability and value, we did not find Cauldhame a useful point of reference when assessing whether the prospective changes to the electricity infrastructure around Spindlewood would have prevented it from being sold, other than at a substantial discount, in March 2020.

92. Mr Greenland next considered the “need to sell” scheme operated by HS2, which he relied on to illustrate the impact uncertainty could have on property values. This is a non-statutory scheme for owner/occupiers who can demonstrate a compelling reason to sell their property but who have been unable to do so except at a greatly reduced price as a direct result of the announcement of the route of the HS2 railway. The property should have been marketed without success for at least 3 months and received no offers within 15% of the realistic unblighted asking price. Mr Greenland explained that the scheme extends to properties situated more than 300m from the line and as at 31 July 2020 285 properties had been purchased under it. He referred to conversations with colleagues who have been involved in managing properties acquired by HS2 and suggested that their intention is to dispose of them after construction has been completed when an enhanced value is expected to be realised following the removal of uncertainty. Mr Greenland had no personal experience of the scheme or any detail about the outcomes achieved by claimants entering into it. He was unable to assist the Tribunal in describing how the HS2 might compare to the installation and removal of pylons and agreed that the only conclusion that could reasonably be drawn from the existence of the “need to sell” scheme was that uncertainty can impact market value. We have no difficulty in accepting that general proposition, which is also supported by Mr Greenland’s Cauldhame evidence, but once again it does not assist in quantifying any impact relevant to this reference.

93. Mr Greenland sought further support for his position by reference to an academic study by Sally Simms and Peter Dent published in 2003. This paper examined the effect of electricity distribution equipment and in particular high voltage overhead transmission lines on the value of residential property in England. The topic was said to be relatively unexplored, in part, due to the lack of transactional data for analysis at that time. The paper compared the results of two UK studies undertaken by the authors. The first was a national survey of property valuers’ perceptions of the presence of distribution equipment near residential property, which was then compared with an analysis of transaction data from a housing estate in Scotland.

94. Mr Greenland said that the authors of the paper had found that the value of property within 100m of a high voltage overhead line (in the case study, 275kv) was reduced by between 6% and 17%, with an average of 11.5%. The presence of a pylon within that distance appeared to have a more significant impact and reduced values by up to 20.7% compared with similar properties situated 250m away. It was noted that pylon impact was greater at the front than the rear of the house.

95. Analysis of the authors’ findings reveals more nuanced conclusions. Despite a sample size of 1,000 valuers and estate agents only 277 responses were useable of which 22.6% had never valued a property adjacent to power lines and nearly half (49.8%) had rarely valued a property so located. Unsurprisingly respondents considered that physical proximity and the visual presence of a pylon had a significant and negative impact on value. The study found that the relationship between reduction in value and proximity to overhead lines was not linear and indicated that for a detached property a reduction of between 6% and 13.3% can be anticipated within 100m of a pylon compared to one situated 250m away. A property having a rear view of a pylon was found to be reduced by an average of 7.1% whereas properties with a frontal view experienced reductions of 14.4%. The authors concluded that all negative impacts appeared to diminish with distance and were negligible at around 250m. Mr Greenland acknowledged that the report did not address different sizes of infrastructure schemes and that the study was based on a large housing estate several hundred miles from the reference property.

96. Mr Greenland’s fourth and final line of enquiry examined negotiated settlements, details of which he had gleaned from colleagues and other agents. Colleagues acting for owners affected by other parts of the Hinkley scheme had provided information about compensation for the effects of new pylons and power lines. Mr Greenland understood that compensation equivalent to 15% to 20% of market value had been agreed for pylons between 100 and 150m from affected properties, but he was unable to provide any detail because the settlements were subject to non-disclosure agreements. In particular, we do not know whether these figures were agreed in cases where pylons were already present in the vicinity of the affected properties but were to be replaced by new infrastructure, which is the particular context of this reference.

97. Mr Greenland was also aware of a significant number of agreements between other power companies and landowners for injurious affection arising from pylons and cables. Agreements were typically reached at between 5% and 10% of the property’s value for pylons situated 50m to 100m from a property but in some instances the figures were higher. Mr Greenland did not however provide any detailed examples and acknowledged that these were cases of agreements between property owners and power companies rather than market evidence. It was a puzzling feature of this category that it was said that in almost every case the agreements related to apparatus which was already in place so that the basis of the claim for compensation was unclear and the element of uncertainty experienced at Spindlewood at the valuation date was not present. It seems to us that this information is too generalised and imprecise to have any reliable bearing on the matter before us and accordingly we attach no weight to it.

98. Drawing these various factors together Mr Greenland concluded that the scheme at Cauldhame and the Hinkley Point connection project were broadly similar and supported the case for a substantial diminution in value. The presence of discretionary blight schemes with a common threshold of 15% also indicated that the proposition that uncertainty and construction disturbance have a significant impact on value is well founded. The information about negotiated settlements established a minimum reduction in value for existing pylons at a similar distance to those at Spindlewood of between 5% and 10%. Applying those conclusions to the works adjoining Spindlewood he considered that were the nearest pylon to be situated at the limits of deviation it would be clearly visible above the roof of the garage which would have a significant adverse effect on value. Even if the pylons were expected to be located at the proposed centre line of the construction corridor, a purchaser in March 2020 without the benefit of the advice of a landscape and visual impact expert would be uncertain whether they would be visible or not, and that uncertainty would have an effect on value.

99. When it came to quantifying the suggested diminution in value Mr Greenland began by considering the presence of the underground cables and the associated rights and concluded that these would lead directly to a reduction in the value of the property. He pointed out that the rights are exercisable at any time and that, just as Mr Mitchell is unable to say to what extent the restrictions or rights would be exercised in practice, the hypothetical purchaser could not have known at the date of the counternotice either. Even a remote possibility of the exercise of these rights would be significant because they permit the excavation of the garden and the demolition of the garage should National Grid need to access the cables.

100. Mr Greenland sought assistance from a decision of the Lands Tribunal, Bestley v North West Water [1998] 1 EGLR 187. That case concerned a large Edwardian house in Stockport which had been sub-divided in two parts. A water main had been laid under an area used for vehicle circulation, parking and as a driveway, close to the eastern corner of the house and diagonally across the level garden area. An easement had been acquired over a 6m wide strip of land affecting an area of 360m2 belonging to one of the occupiers and 128m2 belonging to the other. The Tribunal found that the laying of the water main and the rights associated with it had caused a depreciation in the value of each claimants’ interest of 2.5%.

101. Mr Greenland took the 2.5% depreciation found by the Tribunal in Bestley as his starting point but observed that the area over which those rights had been acquired was far smaller than the area affected at Spindlewood. That case had involved a single pipe rather than two high voltage cables with their associated concerns over electromagnetic fields (EMF). Spindlewood is a high value detached home where the impact of the access for maintenance or repairs would be greater than at the Stockport residences. Mr Greenland’s conclusion was that the likely reduction in the value of Spindlewood caused by the presence of the underground cables on the claimants’ land and the rights associated with them amounted to 5%.

102. Mr Greenland considered that, at the material day, the most important impact of the works from a value perspective was caused by uncertainty over how the property would be affected both during construction and on completion of the scheme. In his opinion that uncertainty, together with the novelty of the new T-pylons, gave rise to an additional loss in value. He considered it unlikely that the prospect of individual parts of the construction process would have caused the hypothetical purchaser to pay a lower price for the property, but the cumulative effect of a number of separate disruptions would either have deterred the purchaser completely or caused them to offer a significantly lower price. Mr Greenland’s conclusion was that, cumulatively, the construction phases, the larger T-pylons and their higher voltage overhead lines, the new underground cables and associated rights, the perceived health risks from EMF, and the general uncertainty and fear of the unknown would cause the hypothetical purchaser to adjust his bid by 25%. When questioned about the relative significance of these components he stated that he regarded each of them as being of equal weight. He had attributed 5% to the underground cables and associated rights, and we understood his view to be that each of the remaining four elements was as significant and that each justified a diminution in value of 5%, thus amounting in aggregate to 25%. Mr Greenland’s conclusion was therefore that Spindlewood could not have been sold in March 2020 unless the claimants had been prepared to accept a price 25% lower than would have been its price but for the Hinkley connection scheme.

Mr Billingsley’s evidence for the respondent

103. Mr Billingsley is an equity partner of Bruton Knowles and is currently Head of Skills with responsibility for the firm’s compensation faculty. He has advised National Grid since 2007, managing over 2,000 claims in that time.

104. In common with Mr Greenland, Mr Billingsley sought to assess the impact of the scheme on the value of the property by reference to the response of the hypothetical prudent purchaser who, it can be assumed, would have made reasonable enquiries and would be aware of information which would be disclosed by the vendor.

105. Mr Billingsley had regard to the evidence given on behalf of National Grid by Mr Mitchell, who explained what information could have been obtained about the Hinkley connection scheme from publicly available sources or from National Grid itself in March 2020. According to that evidence a prospective purchaser could have discovered:

(a) the general requirements imposed on National Grid by the DCO;

(b) that it was proposed that no vegetation in the garden of Spindlewood would be affected by the works, and that no trees or hedgerows would be removed along Cadbury Camp Lane during stage 4 and 10;

(c) that although a construction compound was permitted north of Cadbury Camp Lane it would not in fact be used during stage 4 and the DCO did not permit its use for stage 10;

(d) that National Grid did not intend to of break up the surface of Cadbury Camp Lane;

(e) that National Grid would not alter the layout of Cadbury Camp Lane to create the permitted temporary bell-mouth on the corner with Whitehouse Lane;

(f) that National Grid would only use its powers to close Cadbury Camp Lane temporarily during stage 10 in limited circumstances;

(g) operational access to pylon LD88 would not be taken via Cadbury Camp Lane;

(h) WPD would be unlikely to exercise its right to take access to the property during the operation of the 132kV cables due to the great depth of the cable ducts;

(i) that the DCO required site specific mitigation measures to be approved by North Somerset Council and to be in place during stage 4;

(j) that National Grid did not intend to demolish the claimants’ garage;

(k) that acoustic screening would be in place at the launch pit during the stage 4 drilling works to mitigate noise impacts on the property;

(l) the programme for removal of the existing infrastructure and its replacement by the new T-pylons;

(n) that the construction works in the vicinity of the property would be of limited duration; and

(o) the planned locations of the new T-pylons and their likely dimensions.

106. We do not accept that all of this information would have been readily available to a prospective purchaser making reasonable enquiries, but some of it would. Mr Mitchell is no doubt correct that scrutiny of National Grid’s website or the planning portal would have disclosed the DCO, the works plan, and much, or all, of the other information he listed in his witness statement. But we think it very unlikely that, amongst the huge quantity of available material, a prospective purchaser would have unearthed and assimilated the detail of which Mr Mitchell was aware.

107. Even after making specific enquiries of National Grid we are satisfied that a person with a serious interest in purchasing Spindlewood would have become aware only of the powers themselves, and of the broad details of the works. Specifically, they would have learned that that the existing pylons were to be removed and replaced by new, larger, T-pylons located further away. They would also have discovered that two high voltage electricity lines were to be laid deep beneath the surface of the garden in ducts created by horizontal directional drilling (HDD) from adjoining land rather than by excavation within the garden. This information had been available to Mr Cole since at least February 2014, when a note prepared by Mr Cumpstone of National Grid recorded that during a telephone conversation on 12 February it was explained to Mr Cole that the rights were required over his garden and buildings “for HDD under the garden to facilitate the installation of 132kV cable”, a prospect about which Mr Cole was said to be “not unduly worried”. Mr Cole confirmed that the conversation had taken place and did not suggest that the note was inaccurate. The same information was discussed at a meeting between Mr Cole and Bruton Knowles, National Grid's advisers, on 30 October 2014.

108. A person making diligent enquiries, either directly with National Grid or through solicitors as part of the conveyancing process, would also have become aware that National Grid had all the rights it required to carry out these works, and that doing so might cause temporary inconvenience from time to time over a number of years. We do not think a reasonable person would assume that National Grid was likely to make use of the powers it had in an unreasonable way, or that it would cause disruption which could reasonably be avoided. A reasonable person would understand that work would be conducted intermittently at different points along the route of the Hinkley connection. The prospective purchaser would have known or could have obtained information about the timing of the stage 4 works, which were due to commence within a few months. They would have realised that it was likely that those works would be finished or at least be well advanced well before the end of the year.

109. National Grid provides an information helpline to answer questions from members of the public about the Hinkley connection project, including about the works themselves. In the course of the hearing a dispute developed over the detail which would have been available to a prospective purchaser using this helpline. Mr Mitchell thought that more up to date information would have been provided by the helpline than was available from other sources, but Mr Greenland’s experience when he had rung the helpline pretending to be a purchaser and asking a series of specific questions had not confirmed this. After the hearing National Grid tendered a witness statement from an employee of the helpline operator and Mr Greenland provided a response. We found none of this material of assistance and it simply illustrated that the recollections of honest witnesses on mundane points of detail are liable to differ. We do think the helpline would have been a useful source of information for a prospective purchaser and that it would have assisted in highlighting the broad details of the scheme, as we have described them.

110. Taking the information he understood to be in the public domain as his background, Mr Billingsley then identified three potential areas of impact which would be of interest to a purchaser, namely, construction phase impacts, the long-term impact of the overhead electricity apparatus, and the impact of the underground cables. Mr Billingsley further divided the construction phase impact into the directional drilling undertaken beneath the property, works on Cadbury Camp Lane, and the construction of the new overhead line.

111. The first of these he concluded would not involve physical disruption to the property with the most likely impact being occasional walk-on access by contractors for survey purposes. It was known that the cable laying works at Spindlewood would be undertaken by horizontal direct drilling. Although it had not specifically been confirmed by the contractors that the claimants’ garage would not be demolished they had been advised that the cabling works should cause no physical impact on the property. The only physical sign of the directional drilling was the presence of a vibration monitor and some small marker flags along the route. Any adverse impact would be minimal and would not result in the hypothetical purchaser reducing their bid for the property. National Grid would always have been under an obligation to make good any damage and to compensate the owner. Plans prepared by National Grid showed that there would be no tree removal on the property during the underground cable works, and this was confirmed in the tree and hedgerow protection strategy approved by the local authority in November 2019.

112. Mr Billingsley acknowledged that during the construction period there was potential for works on Cadbury Camp Lane itself and that the scheme would require the closure of the road on four occasions for limited periods to install safety netting during the removal of the existing overhead line. Any hypothetical purchaser could have obtained this information by making enquiries of National Grid. Mr Billingsley noted that other utility companies have rights to undertake works to services in Cadbury Camp Lane and that the works planned by National Grid and WPD would be no more burdensome. The hypothetical purchaser would understand that the road closure would be limited, and it would not detract from the value of the property.

113. The scheme permits the creation of works compounds and activity to install the new overhead line and take down the WPD line. Mr Billingsley pointed out that the construction compound on the corner of Cadbury Camp Lane and Whitehouse Lane had not been required during the stage 4 works and National Grid’s view was that the DCO does not permit the use of the compound for the stage 10 works. He assumed that the hypothetical purchaser would have been aware of this in March 2020.

114. Mr Billingsley thought that the construction of the new overhead line would be substantially screened from the residential element of the property and would only be seen from the edge of the garden. He characterised these operations as being similar to agricultural works with topsoil being removed from the site. The impact on the property would be limited and temporary in nature and, taking into account the mitigation plans, he concluded that during the construction phase it would not be sufficient to materially reduce the amount a hypothetical purchaser would be prepared to pay. Mr Billingsley then turned his attention to what he described as the “impact of the electricity apparatus works” by which he meant the long-term effect of the removal of the 132kv line and the installation of the new 400kv overhead line. He was dismissive of the concerns about the EMF produced by electrical power lines and suggested that there are tens of thousands of houses that are crossed by electricity apparatus that have been the subject of successful transactions.

115. Mr Billingsley described the thought processes of the hypothetical purchaser in deciding whether the forthcoming changes in the apparatus would diminish the price they would offer for the property. The purchaser would note the existing WPD line and its position close to the boundary and would be aware that on the completion of the scheme, the existing overhead line would have been removed and the new 400kv line would be in place. Mr Billingsley also assumed that the purchaser would be aware that the new pylon would be further away from the property than the existing pylons. Although taller than any of the current infrastructure, the new pylons would be sited at a lower level which would limit their visual impact. He assumed that National Grid would provide illustrative material to reinforce this point (although we have seen none other than the images produced for these proceedings).

116. Mr Billingsley then focussed on the impact of the overhead lines using what he described as industry standard methodology for assessing injurious affection. He has undertaken over 2,000 assessments for National Grid and other electricity companies using this technique, which relies on the distance from the nearest façade of the dwelling to the nearest pylon. The result is compared with previous settlements to arrive at an appropriate allowance. In this case existing pylon F21 is about 59 metres from the house and Mr Billingsley considered that this would adversely impact the value of Spindlewood by approximately 6%. The distance to the new pylon (LD87) will be 90 metres and using Mr Billingsley’s method of assessment this would result in a smaller adjustment of only 5%.

117. Mr Billingsley’s experience was that the distance from overhead apparatus is a key determinant in a purchaser’s consideration of impact (a judgment which was consistent with the academic study relied on by Mr Greenland). His conclusion was that, as the new pylons were to be further from the house than the equipment they replaced, their impact on the price which could have been achieved for Spindlewood in March 2020 would have been minimal. In fact, the removal of the existing line and its replacement by the new overhead line would result in a positive impact on value as the hypothetical purchaser would note the position of the new line “much further from the house”. Rightly recognising that a hypothetical purchaser would be unlikely to be in a position to quantify the impact of the modification of the infrastructure using this technique, he nevertheless relied on it to further underpin his view.

The marketing advice given to the claimants

118. We will next consider the evidence of marketing and of the advice the claimants received. Although Mr Greenland placed no weight on the marketing advice received by the claimants in arriving at his conclusions on the impact of the scheme on the value of Spindlewood, that advice had been a prominent feature of the claimants’ pleaded case and, no doubt for that reason, Mr Billingsley considered it in some detail. He concluded that the views of those agents were not based on accurate information about the impact of the acquisition of rights and of the works on the property. If a realistic appraisal had been made on the basis of the information which was available, he was confident the property could have been sold at or close to its market value absent the effects of the scheme.