1.What were the relevant aspects of the common general knowledge of the Skilled Team as at the Priority Date?

(a) (ii) "...first attachment magnet..."

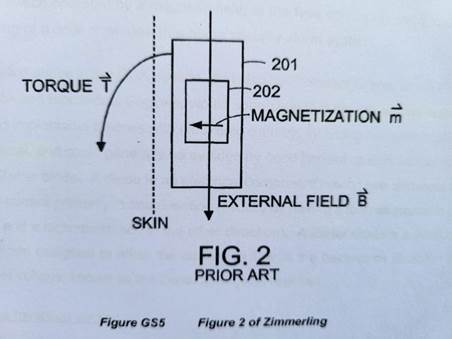

(i) the CGK axial external disk magnet has been replaced by a diametric external disk magnet, and,

(ii) the CGK axial internal magnetic disk has been replaced with a rotatable magnet assembly.

(i) Based on the evidence I consider the headpiece and the external magnet(s) as subsidiary to the main part of the system. In coming to this view I take into account; (a) the common ground that the implant is intended to stay in place for 20 years or so but the headpiece (which I understand would normally include the magnet(s)) are replaced every 2-3 years and are therefore 'relatively' perishable items. It could be reasonably assumed that a patient (I don't believe the route of supply is material here i.e. if via a clinician) would expect to be able to replace external parts which are expected to wear out/take more of a 'bashing' from their day-to-day use, and (b) the significance of the operation of the system as impacted by these external accessories – without the presence of the headpiece the patient cannot hear, without the external magnet(s) the headpiece cannot attach to the implant.

(ii) The implant in the Ultra 3D Device and the headpiece are two parts of a system which comprises a regulated medical device.

(iii) The headpiece/external magnets do not, in my view, embody the inventive concept. As noted above I have held that the headpiece/external magnet(s) play a role in the way the claimed invention works sufficient to classify it as means relating to an 'essential element' of the claimed invention. However, the inventive concept at its core is a compromise to allow enough reduction in torque to make it MRI safe but that in order to maintain a thin housing this should use a rotatable implant magnet which is planar to the coil housing and which keeps its magnetic dipole parallel to that housing (while maintaining sufficient magnetic volume for attachment). The headpiece and the external magnet(s) are a standalone piece of equipment in the patented system. Their design is either entirely unrelated to the inventive concept or – in the case of the external magnet(s) - an inevitable 'knock-on' requirement based on the inventive concept and the chosen specification for the implant magnet (see further reasoning below on the 'knock-on' nature of the choice of external magnet).

(iv) Over the life of the implant the owner of the headpiece may replace it as a damaged/lost external item but presumably could also be upgrading the headpiece or the external magnet(s).

(v) Replacing a component of the headpiece looks more like repair than replacing the entire headpiece with a new one.

(vi) Replacing a damaged or lost external magnet is a relatively small component in the external headpiece and the whole system.

(i) All the claims in issue are obvious over Zimmerling.

(ii) The sufficiency attack fails.

(iii) Had the Patent been valid, claims 1, 10 and 14 as amended would have been infringed under s.60(1) but not s.60(2).

(iv) The Amendment Application is allowed but does not save the Patent from being invalid.

ANNEX B

IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE Claim No. HP-2021-000028 BUSINESS AND PROPERTY COURTS

INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY LIST (ChD) PATENTS COURT

SHORTER TRIALS SCHEME BETWEEN:

ADVANCED BIONICS AG

(a company incorporated under the laws of Switzerland)

ADVANCED BIONICS UK LIMITED

Claimants

- and -

MED-EL ELEKTROMEDIZINISCHE GERÄTE GMBH

(a company incorporated under the laws of Austria)

Defendant

AGREED COMMON GENERAL KNOWLEDGE

The below statement sets out the matters agreed by the parties to be within the common general knowledge of the skilled team at the Priority Date. This statement is provided for the purpose of these proceedings only, and is based on the English legal concepts of the notional "skilled person" (or "skilled team") and the "common general knowledge".

This statement is designed to set out for the Court the matters which the parties agree were CGK in 2010. This is without prejudice to the right of each party to allege (and to dispute) that additional matters were CGK.

Hearing loss and the auditory system (Crane 1 §§46-52)

Hearing loss is the most common sensory deficit to affect humans.

The degree of hearing loss varies on a spectrum from mild hearing loss, through moderate and severe hearing loss, to profound hearing loss. At the mildest level, a patient can usually hear most speech, but certain sounds (such as whispers, or parts of words such as consonants on the end of words) may be hard to hear. At the other

extreme, a patient with profound hearing loss may not hear any speech at all, and may only hear very loud sounds.

Hearing loss can affect just one or both ears; and can be the result of problems in different parts of the hearing system. Typically hearing loss is divided into 'conductive hearing loss' (where the movement of sound through the external or middle ear is blocked) and 'sensorineural hearing loss' (which is a problem with the cochlea or auditory nerve pathway of the inner ear). Cochlear implants are typically used for sensorineural hearing loss patients that cannot get adequate benefit from hearing aids. There are many different causes of sensory hearing loss. The treatment will vary depending on the degree and cause of the hearing loss; and includes use of hearing aids and implants such as cochlear implants.

The structure of the human ear is shown below.

Figure ACGK1 Anatomy of the Human Ear1

The human ear consists of the outer, middle and inner ear and operates broadly as follows:

Sound is a pressure wave that is conducted to our ears by vibrations in the air molecules that surround us. Sound waves are directed by the pinna into the

1 Image taken from Alberti, P.W. The Anatomy and Physiology of the Ear and Hearing. 2006. Available online at https://www.who.int/occupational_health/publications/noise2.pdf, citing Hallowell, Davis and S. Richard Silverman (Ed.), (1970). Hearing and Deafness, 3rd ed., Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

external auditory canal and vibrate the ear drum (also known as the tympanic membrane).

The ear drum transmits energy to the ossicles, which are three small bones in the middle ear, so that sound is conducted to the oval window of the inner ear. The malleus (or "hammer") contacts the eardrum, the incus (or "anvil") serves as an intermediary, and the stapes (or "stirrup") inserts into the oval window.

The cochlea is the part of the inner ear responsible for converting sound vibrations into electrical nerve impulses. The healthy human cochlea is a fluid- filled spiral structure that resembles a snail's shell. It contains two and three- quarter turns and is lined along its entire length with thousands of specialized sensory cells known as 'hair cells'. These hair cells detect sound vibrations and send sound information as nerve signals to the brain along the auditory nerve. Hair cells located at the base of the cochlea detect high frequency sounds, whereas hair cells at apex of the cochlea detect low frequency sounds. As the vibrations move though the fluid in the cochlea, these pressure waves in the cochlea are converted to electrical signals by the hair cells, which are then passed along the auditory nerve to the auditory centers of the brain. When the electrical nerve impulses reach the brain they are perceived as sound.

Hearing loss can result from problems with the outer, middle or inner ear or the auditory nerve and central pathways:

problems in the outer or middle ear conducting sound to the inner ear are known as 'conductive hearing loss'. Many causes of conductive hearing loss can be treated with surgery (middle ear effusion, tympanic membrane perforation, ossicular fixation, otosclerosis, cholesteatoma, etc.). Medical treatment can be effective in some causes of conductive hearing loss such as middle ear effusion. Hearing aids, bone conduction devices, or middle ear implants may be useful.

If the hair cells of the cochlear are missing or damaged, 'sensorineural hearing loss' results. With some kinds of recent onset sensory hearing loss (e.g. idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss) medical treatment such as steroids may be helpful. However, in humans there is currently no way to repair damaged hair cells or the auditory pathways once damage becomes established. The degree of missing or damaged hair cells will affect the degree

of hearing loss. For mild to moderate hearing loss, a conventional hearing aid or other method of amplification may be the best solution. For severe-to- profound sensorineural hearing loss amplification may no longer be adequate, and a cochlear implant may be the best solution.

'Mixed hearing loss' is a combination of both sensorineural and conductive hearing loss. Treatment options include those for each component of the hearing loss.

Cochlear implants

A cochlear implant is a small, electronic device that lets a person who is profoundly deaf or hard of hearing perceive sound. One portion – the external component – is placed on the skin behind a person's ear, while another portion – the internal component – is surgically inserted under the skin. The implant works by directly stimulating the neural tissue within the cochlea with electrical pulses, thus bypassing damaged portions of the inner ear. The implant's signals are sent to the brain, which recognizes the signals as sounds. (Rubinstein 1, §31; Crane 1 §53)

Patients are very involved in selecting a device. (Rubinstein 1, §39 & §46, Crane 2,

§8).

The internal component

The internal component of a cochlear implant device is surgically implanted under the patient's skin with the electrode array sitting inside the cochlea and may be implanted from a few months of age to adulthood. Cochlear implants may be placed in one ear (unilateral) or both ears (bilateral). (Rubinstein 1, §33 & 37; Crane 1 §§53-55)

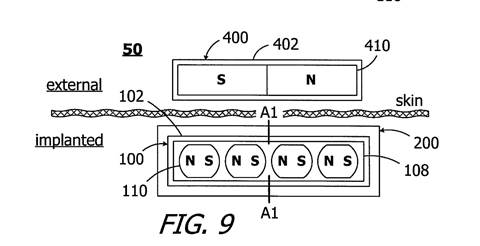

The internal component contains: (i) an RF Receiver coil; (ii) a processor; (iii) a flexible electrode array; (iv) optionally a ground electrode and (v) an attachment magnet. The RF receiver coil receives the transmitted power and data signal. This signal is decoded by the processor. The processor uses the decoded signal to generate electrical signals based on this information, to be sent in each frequency band to a different electrode in the electrode array. (Crane 1 §61-62)

The electrode array, which is inserted in the cochlea, is used to transmit the decoded signals to specific parts of the cochlea. The arrangement of electrodes within the array

mimics the frequency selectivity of the cochlea, in that specific locations of the cochlea are responsible for detecting specific pitches of sound. In this way, the natural hearing process is closely mirrored. (Crane 1 §63)

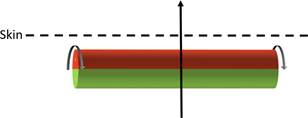

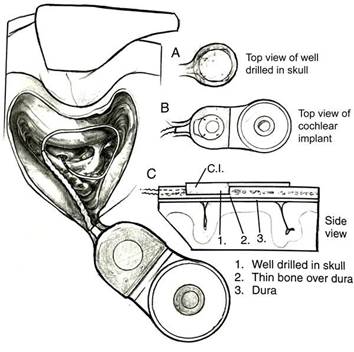

The surgery to implant the internal component typically takes less than two hours. The operation is usually performed under general anesthesia. To summarize the process very briefly, a small incision is made behind the ear. It is then necessary to perform a mastoidectomy (open the hollow, air-filled spaces in the skull behind the ear) to gain access to the facial recess from which the stapes and round window niche are usually visible. The cochlea is usually accessed through the round window, although other approaches to inserting the electrode can be used such as the oval window, or making a cochleostomy anterior to the round window. The processor component is placed posteriorly through the skin incision, so it lies over the skull behind the mastoid bone. A pocket may be drilled in the skull to recess some of the device and the lead that goes to the electrode. In some cases, a larger recessed area can be made in the bone that includes the posterior aspect of the implant including the receiver coil, of the internal component to sit in. This larger recessed area requires more exposure and often a bigger incision. However, devices being implanted at the Priority Date were generally thinner than the earlier devices (such as those with ceramic housings), and did not generally require bone drilling for the posterior aspect of the implant including the receiver coil and the magnet (Crane 1 §64, Parker 2 §7). This is illustrated below2:

2 Figure BC3 from Professor Crane's first report

Figure ACGK2 Internal component of a cochlear implant system following implantation

As illustrated, the housing for the electronics was optionally recessed using bone drilling (Parker 2, §7). However, there was a technique for implantation without any bone drilling at all, the 'sub-periosteal pocket technique', which in 2010 was used on some, but not all, patients. (Rubinstein 1, §53; Crane 2 §16)

The internal component is intended to last for the lifetime of the patient whereas the external component can be upgraded if it is damaged or when more advanced products become available. (Crane 1 §57)

The external components

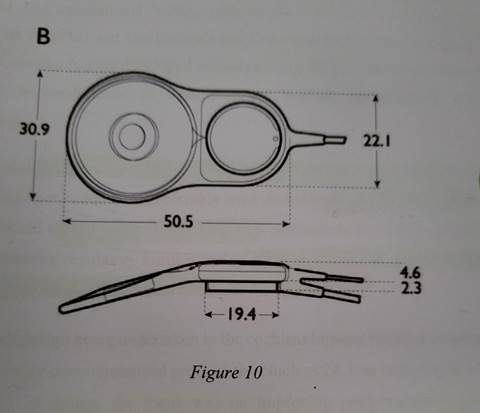

The external (visible) part of a cochlear implant system will comprise microphones, speech processing electronics, batteries and an RF coil to transmit sound and power to the implanted device. In 2010, these components were typically contained in two parts: a part that sat behind the ear and a puck-shaped component containing the RF coil that would sit on the skin over the corresponding RF coil of the implanted device. The puck-shaped component was typically held in place via magnets, one inside the internal device and one inside the external device. (Rubinstein 1, §57)

The external components are easily removable, but the wearer will lose hearing in that ear for the duration that they are removed as the internal component does not have a microphone or independent power supply. (Crane 1 §58)

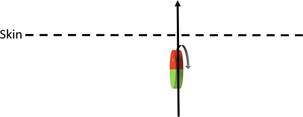

The puck-shaped external component of the cochlear implant is held in place via a magnetic attraction between a magnet that sits in the middle of the RF coil in the internal component and a magnet that sits in the middle of the RF coil in the puck-shaped external component. The magnets also ensure appropriate alignment of the internal and external RF coils. In 2010, the internal magnet was typically disk shaped (Rubinstein 1, §36). The magnets of the internal and external components were axially magnetised and their magnetic dipole was perpendicular to the skin (Parker 1, §52).

It was typical that manufacturers would make the magnet in the external component interchangeable, so that the appropriate strength of the magnet and hence the attractive force between the magnets could be chosen. A magnet that would be too strong would be avoided, as this risks damaging the skin between the magnets during periods of prolonged usage. At the same time, however, it would be important to select a magnet of sufficient strength to keep the headpiece in place. (Rubinstein 1, §58)

Cochlear implant devices at the Priority Date

The three major companies producing cochlear implants at the Priority Date were Cochlear, Advanced Bionics and MED-EL. (Parker 1, §42, Crane 1 §66)

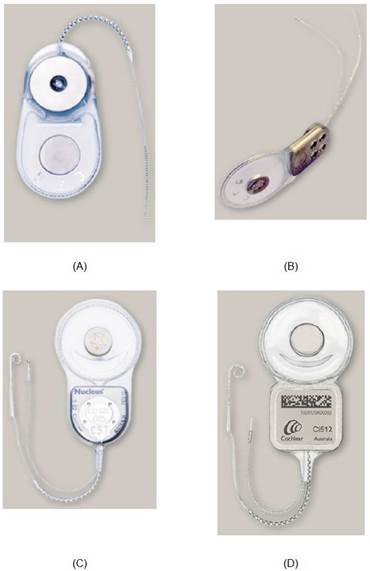

Cochlear launched the Nucleus CI22M system in 1986. The Nucleus 24 was Cochlear's first mainstream commercialized device, and was launched in 1997. It was followed by the Nucleus 24R and Nucleus 24RE implantable devices, in 2000 and 2005, respectively. At the Priority Date, Cochlear's most recently launched product was the Nucleus 5 implant, launched in 2009. (Parker 1, §43, Crane 1 §70)

Figure ACGK3 Cochlear's Nucleus CI22M, CI24M, CI24RE and CI512 implants

For the design of the Nucleus 5 implantable component, Cochlear adopted a titanium (i.e. non-ferromagnetic) casing which encapsulates the electronics, coil, and attachment magnets. The electronics are housed within the square element of the implantable device, underneath the portion bearing the branding and bar code. The circular element contains a coil for power and data transfer, at the centre of which is the attachment magnet with a thin disk shape. As shown in Figure ACGK3 above, the earlier Nucleus 24RE adopted a similar design, as did its predecessors, the Nucleus 24 and Nucleus 24R (Parker 1, §44). In the Cochlear Nucleus 24, and all Cochlear devices thereafter available at the Priority Date, the magnet was removable. (Crane 1,

§70)

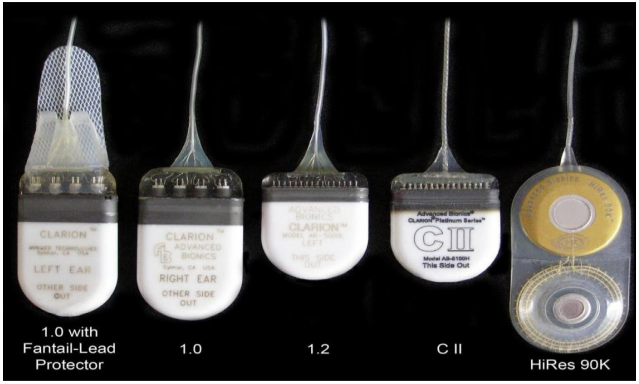

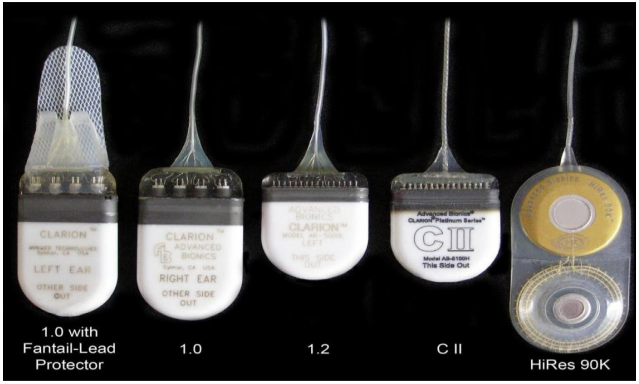

Advanced Bionics launched its Clarion cochlear implant in 1996, its Clarion CII in 2001 and its HiRes 90K cochlear implant in 2003.12 The Clarion and Clarion CII had a ceramic case, which contained the attachment magnet, electronics and coil, whereas the HiRes 90K had a titanium casing for the electronics and a circular element in a silicone case containing the coil with a replaceable magnet at the centre. Unlike the earlier Clarion and Clarion CII models, the internal magnet of the HiRes 90K could be removed for MRI scans. (Crane 1 §73, Parker 1, §46, §48)

Figure ACGK4 AB Clarion, Clarion CII and Hi-Res 90K devices3

MED-EL launched the Comfort cochlear implant in 1989, the COMBI 40 in 1994, the COMBI 40+ (C40+) cochlear implant in 1996, the PULSAR cochlear implant in 2004 and the SONATA cochlear implant in 2006. The PULSAR device had a ceramic casing, whereas the SONATA device had a titanium housing (Parker 1, §47-48; Crane 1 §71). MED-EL did not use removable magnets before the Priority Date (Crane 1 §72).

3 Figure BC6 from Crane 1

Figure ACGK5 PULSAR and SONATA MED-EL devices

By the Priority Date, the three most recently launched devices had a titanium case for electronic components with an external coil in the centre of which contained a titanium encased disk-shaped rare earth permanent magnet. There was a slim housing containing the receiver coil, the implanted magnet and a silicon chip for processing sound; and an electrode array for insertion into the cochlea. (Parker 1, §51; Suaning 2, §11)

The coil housing in these devices was essentially flat and planar. Likewise, the portion of the implant which houses the electronics was flat. While the two halves of the implant were each flat, they were angled relative to each other in order to conform better to the natural curve of the skull. (Parker 1, §51, Crane 2, §10)

The implant magnet in each of these devices was disk-shaped and its magnet dipole was oriented along its central axis (i.e., perpendicular to the skin). (Parker 1 §52)

As well as the need for a low-profile, other design considerations at the Priority Date included: reliability, regulatory compliance, suitable attachment magnet strength, and compatibility with external devices such as MRI scanners. (Rubinstein 1, §49-54; Parker 1, §53-56; Suaning 1, §61; Crane 1, §74-83)

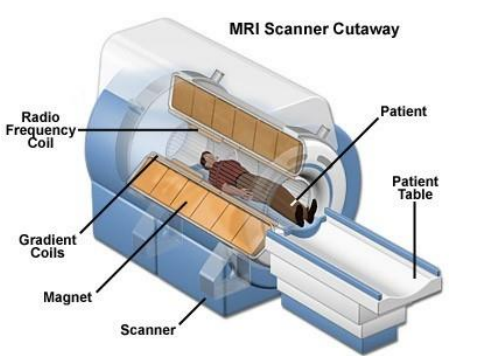

Magnetic resonance imaging

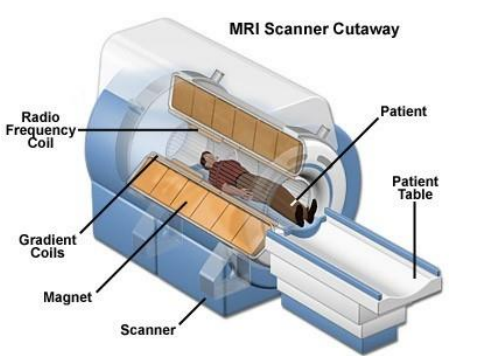

Magnetic resonance imaging ("MRI") is a non-invasive technique in which magnetic fields are implemented to scan and image soft tissues for clinical use. The MRI scanner features a cylindrical construct with a central bore as shown in the diagram below. The cylinder houses an electrical coil formed of superconductive material which is maintained at a very low temperature by continuous cooling with liquid helium. In its superconducting state, the coil can sustain a large electrical current and so generate a very strong magnetic field. The MRI machine is therefore a large electromagnet which can produce a very significant field. (Parker 1, §28).

Figure ACGK7 example of closed bore MRI machine

The number of MRI machines in use had risen between 2000 and the Priority Date; there was an increase in the popularity of MRI as a diagnostic tool in the period up to 2010. (Rubinstein 1, §§60-62)

MRI systems are classified by the strength of the static magnetic field measured in tesla (T). At the Priority Date, the most common MRI machine in clinical use was 1.5T but 3T machines were becoming more common. (Parker 1, §31-32; Crane 1 §74)

There are two major types of MRI machines in clinical use: closed bore machines and open systems.

Closed bore machines employ a donut shaped magnet system and the patient is passed through the centre of the donut. When the patient is placed into the bore, the static magnetic field lines are aligned from their head to toe – i.e. along the length of the patient. (Parker 1, §33)

Open systems are open on three to four sides depending on manufacturer and model. The magnet strength in these machines is lower than closed bore machines (typically 0.35T to 1.2T) which results in reduced image quality which takes longer for imaging (typically 1.5 times longer) when compared to closed bore MRI.

Figure ACGK8 example of Open Bore MRI Machines

MRI machines and cochlear implants

A number of problems and potential hazards arise when ferromagnetic or magnetic material is placed in a strong magnetic field, such as the introduction of the implanted component of a cochlear implant into an MRI machine. At the Priority Date four known potential interactions for cochlear implants were4:

Torque: the strength of the main magnetic field is so great that when the magnetic dipole of the implanted magnet is not aligned with it, the implanted magnet experiences a torque. This can cause the implanted magnet to be dislocated, causing improper function to the device, and pain and potentially tissue damage to the patient.

4 Parker 1, §36; Rubinstein 1, §64; Suaning 1 §78 - 82; Crane 1 §78 - 83; Crane 2 §18

Demagnetization: where a permanent magnet is held in misalignment with an external magnetic field, it can lose magnetization and its magnetic dipole can become weaker.

RF heating: The oscillating frequency field can induce a current in electrical conductors. The current arises as an eddy current, circling within the wires of the implant rather than flowing around a complete electrical circuit. The resistive heating caused by the eddy current causes the wire to become hot, which can damage components. Temperature rises from this effect could also result in burning tissue.

Artifacts: the presence of metal components will produce artifacts on the MRI image in the location of the metal component. The quality of the image depends on the homogeneity of the magnetic field gradient. The presence of a metal changes the uniformity of the magnetic field gradient and results in distortion of the image in the location of the metal component.

RF heating and artifacts problems arise only when the MRI machine is scanning and imaging a patient (with artifact problems only arising when the area being imaged is near to the implanted portion). Torque can be experienced by the magnet when the patient enters the room and becomes worse as the patient approaches the MRI machine. This is because the magnetic field of the MRI scanner extends outside the bore (but is stronger closer to the bore). Cochlear implant users remove the external headpiece of their device before entering the room with an MRI machine. (Parker 1,

§37 & §38)

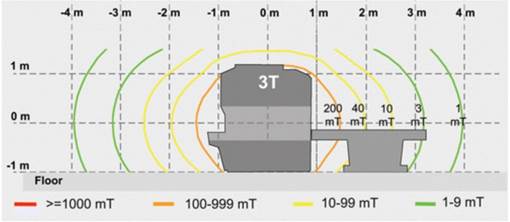

The following figure shows the strength of the magnetic field extending from the bore of a 3T machine. (Parker 1, Figure 6)

By 2010, clinicians would be aware of three options for cochlear implant users:

Avoid MRI scans.

Have the user undergo two surgical procedures to remove and subsequently replace the implant or the magnet before and after the scan.

Wrap the user's head with a supportive bandage and sometimes secure a support over the implant site.

(Rubinstein §68; Crane 1 §86, 90 - 95)

Kirkland & Ellis International LLP

Powell Gilbert LLP 10 February 2022